This busy LA immigration court is now a ‘ghost town’ in wake of government shutdown

People sit on the steps outside Los Angeles immigration court, which has been closed since Dec. 22 due to a partial government shutdown over funding for a southern border wall.

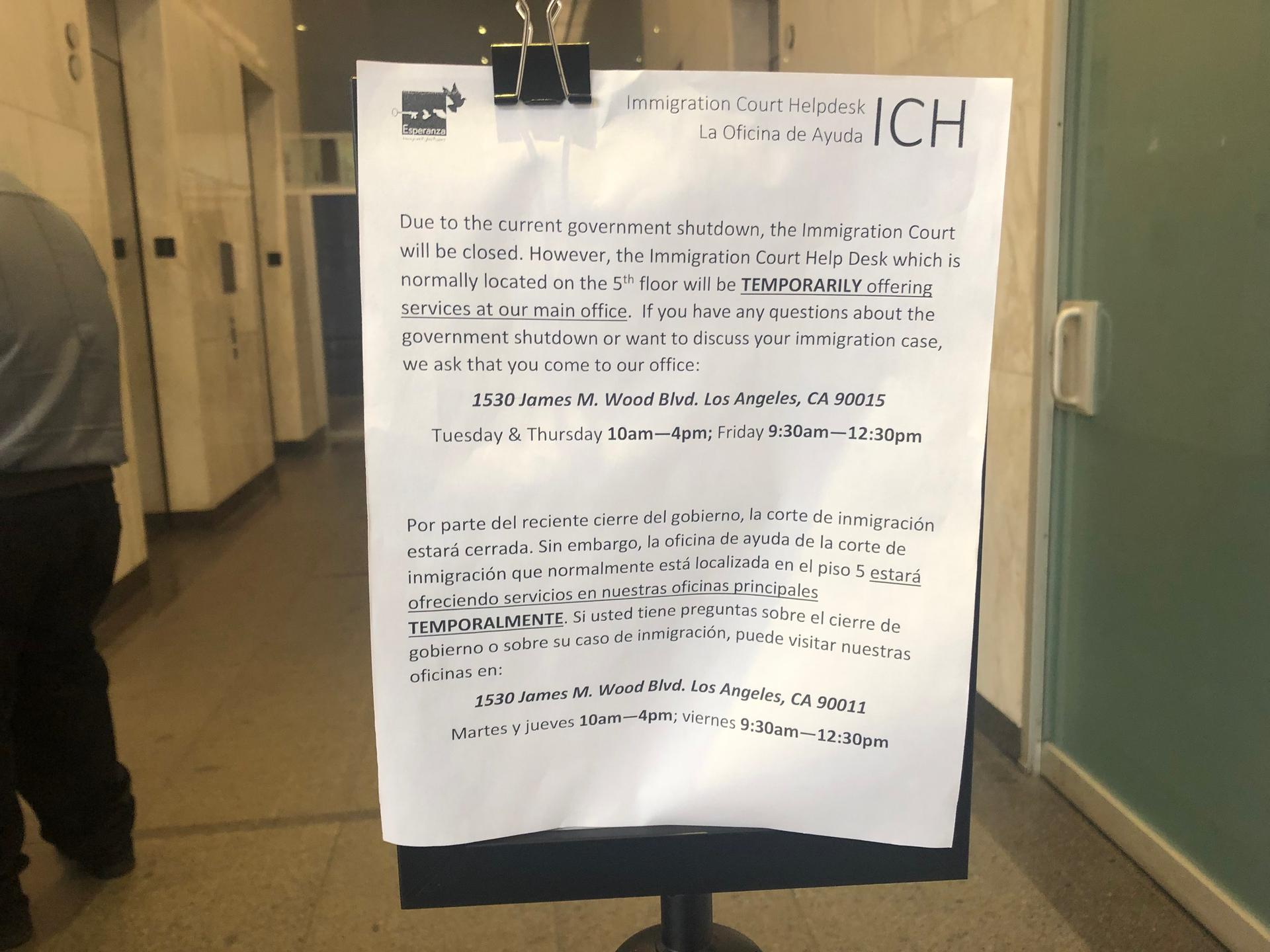

In the lobby of the US immigration court building in downtown Los Angeles, there’s a notice informing visitors the court is closed because of the partial government shutdown. And if you miss it, the security guards will let you know the court is closed until further notice.

Normally this is one of the busiest immigration courts in the country, with more than 76,000 cases pending. Many of those cases involve people seeking asylum in the US. Immigrants, their lawyers, and government attorneys file in and out of the building for dozens of hearings daily.

But all of that came to a grinding halt on Dec. 22, when the government closed over President Donald Trump’s request for $5.7 billion to fund a wall to end what he calls a “security crisis” on the southern US border.

The court is a “ghost town,” says Ashley Tabaddor, a judge assigned to the Los Angeles immigration court and the president of the National Association of Immigration Judges. The nation’s understaffed immigration court system was already struggling with a crushing backlog of cases, and the shutdown only makes that worse.

“It means that thousands of cases across the country are being canceled on a daily basis,” says Tabaddor. “We have well over 800,000 pending cases for just a little bit shy of 400 judges.”

Related: Inside one of the busiest immigration courts in the country

Many of those judges, as well as court support staff, have been furloughed without pay. Hearings for detained immigrants have continued as scheduled — it’s the “non-detainee docket” that’s stalled.

The shutdown means a longer wait for people who have business before America’s immigration courts, including those petitioning for asylum. And some of their cases, says Tabaddor, might be moved to the back of the line when the government does reopen as a way to deal with scheduling gridlock. Some had already been waiting three or four years for their day in court.

California has the biggest immigration court backlog in the country, with an average wait time of 730 days, or two years. Nationwide, the backlog has grown by almost 50 percent since Trump took office two years ago, according to data from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. As of Jan. 11, nearly 43,000 cases are estimated to have been canceled nationwide, TRAC said. California has seen the most cancellations — about 9,000 — followed by New York with more than 5,100.

Outside the Los Angeles courthouse, people who’ve come for their scheduled court dates linger on the front stairs after being turned away in the lobby.

Vicki Guzman is from El Salvador and has legal status here, but she’s trying to get asylum for her teenage daughter because of violence in her native country. The mother and daughter have waited a year for their court date.

“I’m waiting for the court and they canceled it,” Guzman says. “But I’m hoping for something better for my daughter, a better future for my daughter with political asylum, so she can study here and do more with her life. I don’t want her to suffer the way that I suffered.”

Related: What’s the economic impact of a government shutdown?

For some immigrants, the partial shutdown brings unintended good luck: it gives them more time to gather documents and evidence that could strengthen their cases. For others, it only prolongs the uncertainty around their lives in the US — and if immigration policies change, they may qualify for fewer forms of legal relief in the future than they do now.

Tabaddor notes the irony that a standoff over a border wall that’s supposed keep out undocumented people out of the US has paralyzed a court system that’s essential to deporting them. In other words, the shutdown has jeopardized Trump’s deportation machine — and the wall may not tackle the root of the problem: Since 2007, people who illegally overstay their visas have outnumbered those who illegally cross the border by more than half a million, according to a study by the Center for Migration Studies, a think tank.

“We are absolutely flabbergasted that the immigration court would be shut down over immigration,” Tabaddor says.

Related: The ‘real’ border crisis: The US immigration system isn’t built for children and families

Tabaddor also says she’s worried about the financial bite of the shutdown, both for herself and the court’s support staff, like clerks and secretaries.

“I know most of our support staff are not in a position to be able to live off of savings,” she says. “There are, I’m sure, some who are perhaps living paycheck to paycheck. Missing one paycheck is going to have a tremendous impact on them.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!