A ball of mouse skin could lead to new insight in human skin generation

The generation of a ball of mouse skin through stem cell work has created excitement within the scientific community about possible new insight in skin formation — especially on humans.

Call it a pleasant surprise — or a maybe a big hairy deal would be more accurate. At first, a group of researchers from the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis were trying to develop inner ear tissue of a mouse using stem cells.

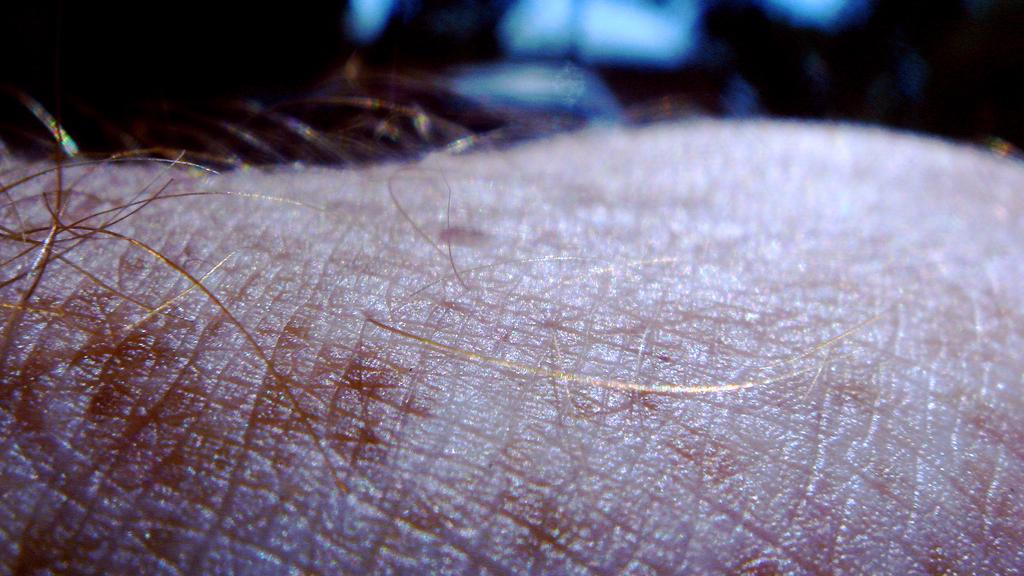

What they ended up doing — as chronicled in a new academic paper in the journal Cell Reports — was essentially create an inverted ball of mouse skin, complete with the epidermis (outer) and dermis (inner) layers as well as hair follicles.

“It wasn't very surprising to us that we were able to generate skin as kind of a byproduct of generating inner ear tissue,” says Karl Koehler, assistant professor of otolaryngology (as in ear, nose and throat) at IU’s School of Medicine. “However, we were kind of surprised to see both layers of the skin developing … and those cell layers interacted in such a way that allowed hair follicles to develop. It was a bit of a shock to see that in the lab.”

One of the revelations of the study, Koehler says, was to witness how the epidermis and dermis grew together, developing simultaneously into the shape of a cyst, giving the structure its ball-like shape with the inside of the cyst representing the epidermis and the outside of the cyst representing the dermis. In addition, the roots of hair follicles were growing outward in various directions “kind of like the pedals on a flower” — in Koehler’s words — and the hair shafts were growing inside the skin’s organoids.

The team’s findings could have a tremendous impact on being able to grow the human variety of skin using the same technique with stem cells — such as a permanent solution to baldness.

“[That’s] been mentioned, but I think the main focus right now is trying to figure out and use this [research] to study the developmental biology of the skin and understand how hair follicles develop to begin with,” Koehler says.

The scientific community’s collective understanding of that process is rather shallow because of the highly complex nature of skin growth, Koehler says.

"I think it's underappreciated in its complexity because it does have these two basic layers, but it's also embedded with these appendages, which in and of themselves, there are there are seven to eight different layers of specialized cells within one hair follicle and they all have special function within the developing hair follicle and then the hair follicle goes through a regenerative cycle over time, over our lifespan, constantly degenerating and then regenerating itself.”

Furthermore, there are resident stem cells within the hair follicles that are governing this process — and interactions between the blood vessels, the immune system and nerve endings to consider, he says.

Still, Koehler’s team has already spearheaded more related research. The team is trying to intentionally take the model of mouse skin as a template to generate hairy skin from human stem cells and then go from the cystic formation, which has proven to form as an inverted ball, to a more normal-looking skin formation that could used to generate skin organoids.

The team is also trying to gain a better understanding into why it was able to able to cross this new threshold in solving one level of the complexity of skin.

“We think it has something to do with the way that the cells develop together versus past attempts where people have tried to take the individual components of the skin and kind of smash them together in a dish,” Koehler says. “And that approach has never really led to the complexity or the cellular diversity that we see in normal skin and it certainly hasn't produced hair follicles in a culture setting."

Koehler says that it has been shown that genes expressed in the dermal cells on different parts of the body appear to have a different signature. He and his colleagues believe that the dermal cells actually instruct what type of skin the body generates based on these signatures.

“An interesting aspect of this study is that since we're kind of slightly tweaking a method for generating inner ear tissue, we are thinking that the skin that's generated is probably similar to the skin that you see on the outer ear or near where that ear develops. And so… being able to generate site-specific skin might be an interesting thing to look at in the future.”

The knowledge gained in this research could also help lead to a method of reconstructing somebody’s outer ear of a person who is born with a congenital disorder that leads to the malformation of inner ears, Koehler says.

This article is based on an interview on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.