Venezuelans fear ‘Fatherland Card’ may be a new form of social control

Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro speaks during a news conference at Miraflores Palace in Caracas, Venezuela, Dec. 12, 2018.

When Reuters revealed in November 2018 that the Venezuelan government had contracted with the Chinese company ZTE to develop a national biometric identification system, public reactions were mixed.

The report stirred outrage both in Venezuela and internationally. But for those who have closely followed the Venezuelan government as it has tightened its grip on people’s data and communications, the report represented yet another chapter in a very long story.

The report confirmed suspicions and denunciations made months ago, increasing fears that the alliance with ZTE will bring Venezuela closer to the implementation of a social credit score system similar to what is used in China. This system would determine which citizens have access to basic services based on their political allegiances. It also prompted the US government to initiate investigations into the role of ZTE in Venezuela.

How is the Fatherland Card used?

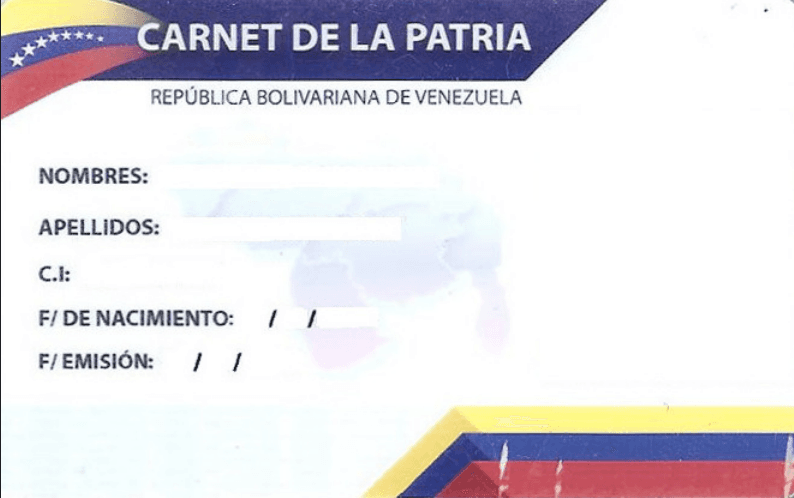

The Reuters story pointed to the participation of ZTE in the development of a monitoring system whose primary tool is the “Carnet de la Patria”, or Fatherland Card. This identification card captures multiple pieces of personal data coupled with a unique and personalized QR code. It also serves as a digital wallet within an electronic payment system.

The government has strongly promoted the Fatherland Card as a way to facilitate multiple public services. The card can be requested voluntarily and free of charge. During this process, whoever wants to get a Fatherland Card must answer questions about their social and economic status.

Those who have the card gain access to food and medicine, which have become dangerously scarce amid Venezuela’s political and economic crisis. They can also access certain government bonds and gasoline discounts, which are newly important. After decades of reasonable local rates, gas prices are now competitive with international rates.

In principle, the Fatherland Card was introduced as a way to streamline the state-administered distribution of food. More recently, the card has been integrated into state processes for accessing legal and personal documents, which can be extraordinarily difficult to obtain in Venezuela.

It is estimated that more than 70 percent of Venezuelans are already carrying the Card. And although many of them identify themselves as followers of chavismo (the political ideology of president Nicolás Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez), Venezuelans who identify as opponents of the dominant political ideology have also registered with the system in order to access personal documents.

The benefits of the Card have accumulated over time. At the beginning of 2018 (a month and a half after the presidential elections), Nicolás Maduro announced that the Card would be required for access to housing bonds and pension payments.

The Fatherland Card and social control

Some experts say the Fatherland Card has other objectives. Fiorella Perfetto of Caraota Digital maintains that the signing of contracts between the Venezuelan telecommunications company and ZTE in February 2017 is part of a larger scheme that was formulated by former President Hugo Chávez with China at the beginning of the mandate.

In 2016, technologist and writer Omar Castro analyzed a number of tweets related to the issue, remarking on people who compared the Card with ration cards:

The Card was also the focus of criticism during the 2017 regional and municipal elections, as well as the 2018 presidential elections.

Many voters reported that when they arrived at the polls, there was a “Fatherland Card booth” a few meters away from the polling station. Voters who had a Fatherland Card were encouraged to register at the booth and were promised special access to food and subsidy bonuses if they did so.

Voters who did not have a Fatherland Card had different experiences. Some were encouraged to sign up for the system, while others were coerced to do so. A few even reported that they were told they could not vote if they did not sign up for the Fatherland Card.

At the same time, opposition campaign workers in Maturín reported that three polling places did not allow citizens to vote if they did not present a Fatherland Card.

The Card is intended to address the country’s limitations on access to cash, hyperinflation and the serious lack of food and medicine. But it can also be seen as part of a wide-ranging state effort to control information, whether private or public. This has also included internet outages, attacks on online media, and the continuous censorship of media not aligned with the government and due to lack of paper, among other resources.

Victor Drax, from Caracas Chronicles, an independent media collective, commented on what a monitoring system like this may mean for those who use it — and for those who do not:

Remember what we’ve been saying about the ‘carnet de la patria’ as an instrument of oppression? Reuters just published a thorough investigation about the thing, and it’s so fucking perverse, it’s baffling […] You know what this means? After you get on the system, the State can come directly to you and say ‘I know your mother needs medicine. I have it, and you’ll only get it if you do what I want.’ This is how the State knows what to do when the time comes to exploit us.

A series of pieces published online by local and international media, as well as online conversations, continue to make it clear that the card is only one in a long series of efforts to isolate the nation and control the population. They show that these efforts did not begin with Nicolás Maduro’s government and permeate in ways that cannot yet be fully understood.

Following the same ideas, Drax concludes:

Now you see why Nicolás [Maduro] has been so desperate to get everyone on board with the Fatherland Card […] To say that this tramples over the Constitution is an understatement, especially after 20 years of chavismo. Want to know the best part?

This all came from Hugo Chávez himself.

Laura Vidal is the Latin America editor with Global Voices.

This article is translated by Alexis Faber and republished from Global Voices with Advox under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.