International lawmakers seek global regulations for social media

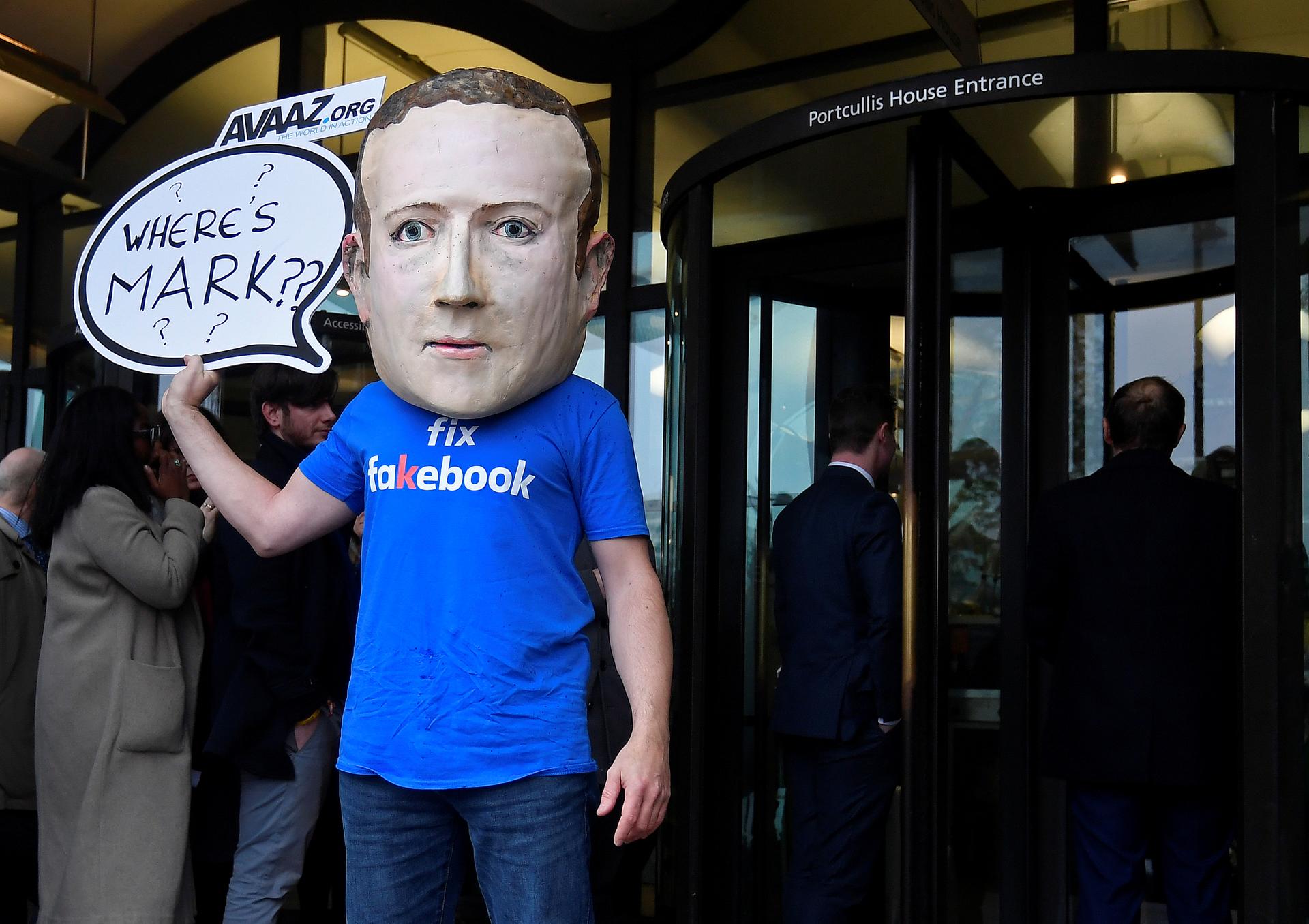

A campaigner from a political pressure group wears an oversized mask of founder and CEO of Facebook Mark Zuckerberg after he failed to attend a meeting on fake news held by Parliament’s Digital, Culture Media and Sport committee in London Nov. 27, 2018.

For the first time in decades, the UK and nine other countries convened at the British House of Commons as an opportunity to address issues around disinformation, fake news, electoral interference and data misuse — all things Facebook has been used for to disrupt democracies around the world.

Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg declined several invitations to attend the hearing and instead sent Richard Allan, another top Facebook executive. Needless to say, the panel of lawmakers were less than thrilled.

“We’ve never seen anything quite like Facebook where, while we were playing on our phones and apps, our democratic institutions, our form of civil conversation, seem to have been upended by frat boy billionaires from California,” said Canadian representative Charlie Angus. “So Mr. Zuckerberg’s decision not to appear here at Westminster [Britain’s parliament], to me, speaks volumes.”

Angus was among the two dozen reps at this morning’s hearing who were very eager to get face time with the company. One member of parliament from Singapore said her team was willing to travel halfway around the world for the opportunity.

Canadian representative Angus said that at this point, Facebook has “lost the trust of the international community,” and that it can no longer be left to police itself — it needs to be regulated.

Some countries already have regulations in place to prevent bad actors from misusing Facebook and other platforms.

Related: Brazil fights online misinformation during election season

Germany has one of the strongest laws when it comes to fake news and disinformation. Big tech companies that operate there are required to take down this type of content quickly or they face a fine.

And when it comes to issues of data and privacy, the EU has some of the strongest regulations — like the General Data Protection Regulation, which was put into place in 2016.

But those gathered at the House of Commons seemed to agree that it’s still not enough.

One of the people who spoke today was Brazilian politician Alessandro Molon. His country recently had a federal election where they saw an extreme level of fake news and disinformation spread through WhatsApp, the messaging platform owned by Facebook. Viral misinformation included an anti-vaccination hoax about yellow fever and false instructions on when to vote.

Related: Angry at status quo, Brazil’s voters open a door for the far right

“The same democracy that allowed social media to flourish should now be protected by social media,” Molon said. “There is, however, a unique challenge. The internet doesn’t respect borders. Which poses a challenge to national legislation.”

Irish politician Hildegarde Naughton proposed that perhaps Facebook and other social media platforms need regulation on a global level.

“… We should be accountable for you,” Facebook’s Allan responded. “We should tell you what we’ve done and if you’re unhappy, you should have the power to take sanctions against us. I completely accept that principle.”

Facebook seems more open than ever to regulation.Allan did say he doesn’t think Facebook should be held legally responsible for everything on its platforms, but added that the idea that Facebook should be exempt from everything is “out of date.”

One idea suggested by Naughton was a set of regulations through the United Nations or another intergovernmental agency, but it’s unclear what that set of global standards would be. What is clear: a piecemeal approach to regulating social media is nearing an end.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?