‘We were born refugees’ — Lebanon’s forgotten refugee camp

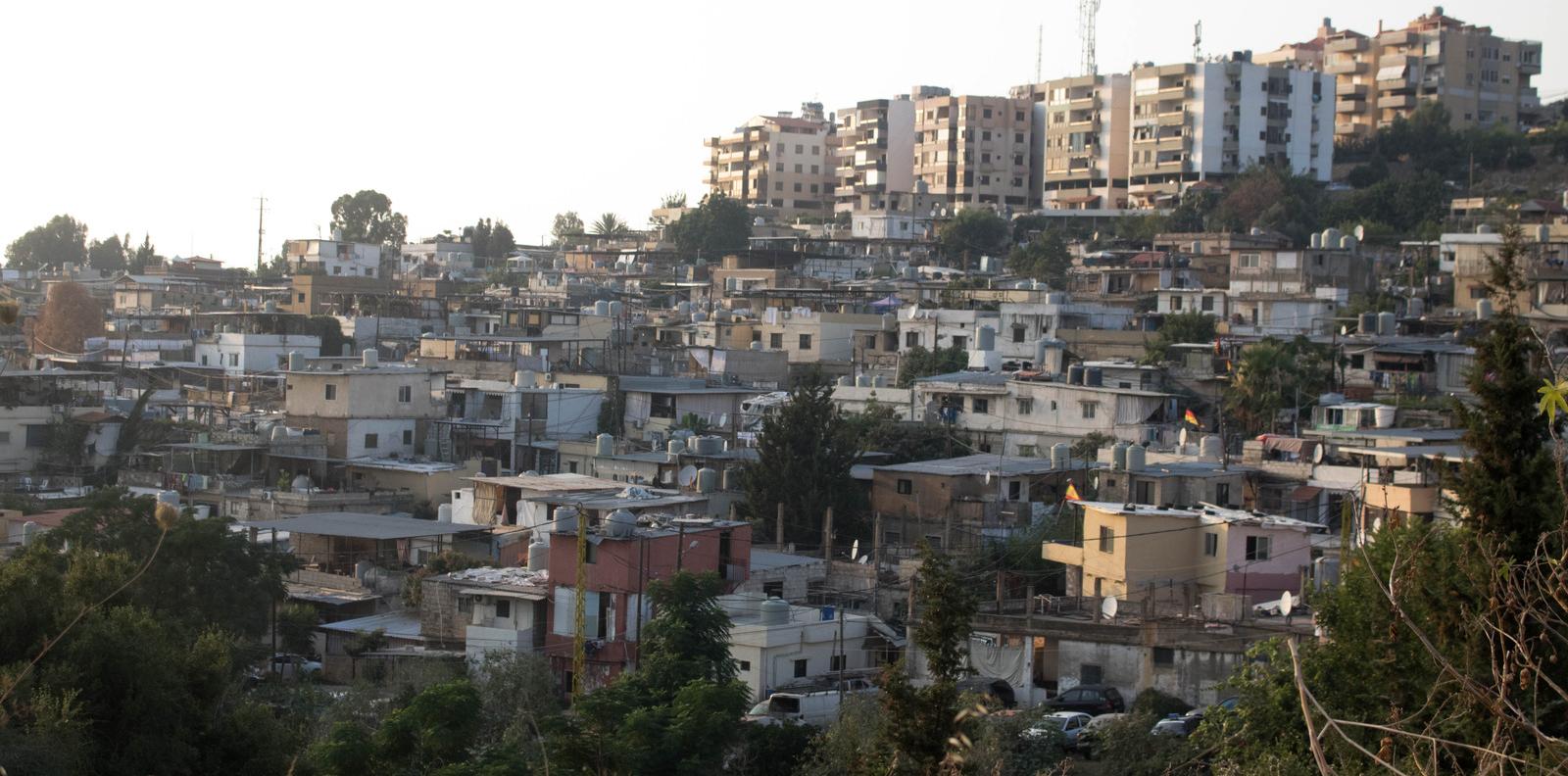

Around 520 families from Palestine and Syria currently live in Dbayeh refugee camp in Dbayeh, Lebanon.

Standing outside a worn-down school in the Dbayeh refugee camp, a group of residents prepares to replace the school’s door when they are suddenly stopped by the police. They are told that if they continue, they will be fined.

Why? As Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon, they are not allowed to build or repair property.

Palestinian refugees face strict labor laws preventing viable employment. Some take on odd jobs in the hopes of making enough money to feed their families.

Many Palestinians fled in 1948 during the war with Israel, with some going to Jordan, Syria or Lebanon. During the 1967 war, more Palestinians were forced to leave.

The Dbayeh refugee camp in Dbayeh town is a Palestinian Christian camp established in 1951, when Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat rented the area prior to Lebanese government restrictions on Palestinian land rights.

Currently, the camp is home to around 520 families. Fifty of those families are Syrians who came to Lebanon after the civil war broke out in their country in 2012.

Related: After Trump’s ban, Lebanon renews calls to send back Syrian refugees

Elias Habib, who heads the Dbayeh committee of camp members who manage camp operations, says Dbayeh was one of the first places to offer refuge to Syrians fleeing war.

The camp was created by Palestinian Christians to provide a home for those who face double discrimination: from the Lebanese as Palestinian outsiders and Palestinian Muslims as Christians, according to Habib.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) funds camp operations, but limited funding and resources mean the camp can only do so much.

The camp’s school is in an extreme state of disrepair. The walls are pocked with large holes and the doors are falling off their hinges.

Habib said many of the children in the camp no longer study at the camp school. Rather, they go to the local public school or — if they can afford it — private schools.

“In other camps, the UNRWA supplies that [education] for free. Just not here,” said Habib. “[At other camps] they pay for everything, including transportation.”

“As Palestinians, we are not allowed to reconstruct anything here because it is against the law,” said Habib. If residents repair anything in the camp, they rely on UNRWA documents to support these decisions. If not, they could be fined 1 to 3 million pounds ($662-$1,974) by the police.

UNRWA hasn’t done anything substantial about this issue, said Habib.

“The UN has the authority to build and rebuild and do whatever they need to do because they rented the land,” Habib said, “and they have the actual documents to do something. However, they simply don’t do anything about it.”

Palestinian activist Samir, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, agreed.

“UNRWA has done almost nothing for Dbayeh,” said Samir.

The UNRWA did not respond when asked for comment.

Habib offers an example of a man in the camp who tried to rebuild his porch this past summer.

According to Habib, the man was stopped from completing the repairs because someone had called the police to report his building project.

“They should call the police if something is illegal. But we have the legal right to rebuild whatever we need to rebuild [with UN support] and the UN itself is not applying those rights,” said Habib.

When the camp needed to replace a few doors on the school, the police were called again and they were forced to stop.

This time, however, Habib used his connections to get permission to replace the doors. Another time, even when they went through a legal process, they still faced conflict with the police.

When the Dbayeh committee wanted to refurbish an old, rusty building, they alerted the nearby monastery, spoke with the UN, went to their local municipality and received the proper forms to complete the construction. Even so, Habib says the police were still called more than 30 times.

Complaints against the committee surfaced and then fixated solely on Habib as an instigator.

Parched for resources

The 450,000 Palestinians refugees seeking work in Lebanon have limited options. Palestinians are allowed to work in the private sector, but would-be employers still face fees and bureaucratic hoops that make employing Palestinians difficult. Many are forced to work informally and with limited legal protections.

Dbayeh camp residents struggle to afford fees for school, medication, food and clean drinking water.

“There is no tap water or drinking water,” Habib said. “We have to buy bottled water to drink and we buy tap water to work with. “There is no actual supply of water in this area for us.”

Since Syria’s civil war erupted, an influx of two million Syrian refugees in Lebanon has complicated the situation.

“It was hard for us before and now it is even hard to find work since the Syrians came, because they are accepting minimum wages or even less than that,” said Habib. “We’re not really able to save any money even though we are working double shifts. We’re barely living. It’s very hard for us as Palestinians to find a job. Any jobs with a union are forbidden for Palestinians. Even working as a taxi driver.”

According to Samir, Palestinians face discrimination in the job market.

“When we apply, the second we are known to be Palestinians they act as if they don’t need anyone anymore. And if we are accepted, we work for less income. I know a person that has a PhD in chemical engineering from Baghdad who works as a janitor. I also know a lawyer who works illegally as a taxi driver and if he is caught, then he will be fined.”

Samir also struggled to find employment.

“I once tried to work in a pharmacy. I was sent to the store that was [far] away from anyone so that the pharmacy wouldn’t have to pay the fee of 1.5 million pounds ($1,480) for having a Palestinian work there. I didn’t last a week. I was angry and quit myself. I once applied for a teaching position with a friend who is Lebanese with exactly the same degree as me. It was a small college that is meant to help all kids. My friend was accepted, and I was asked to leave.”

As a Christian camp, the Lebanese often assume the refugees are living in better conditions than other refugee camps, said Habib.

“Other people [are] convinced that because we are Christians we are living a better life than other camps until they actually come here and see the truth for themselves — that we aren’t actually living with any basic rights.”

“You are treated as something lower than what the Lebanese are mostly. This is especially so if you speak with the Palestinian [Arabic] accent,” said Samir. As camp conditions continue to deteriorate, Habib is now contemplating leaving Lebanon, but he doesn’t want to abandon his community. And his Palestinian passport makes travel more difficult.

“The whole situation in the country is getting worse regardless of us being Palestinian or not. It is really, really bad for us. It is getting worse now. I didn’t want to leave the country, but, now, I am reconsidering because we have been left with no other options,” said Habib.

“We are the only people born as refugees.”

As more Syrians settle at Dbayeh, the camp has received increased funding from various international nongovernmental organizations, but the committee wonders what will happen to the extra funding when the Syrians return home.

“Most of the funding after the start of the Syrian [refugee] crisis went to the Syrian issue. … In 2020 or 2021, the Syrian issue will be solved because either they will return to their homeland or they will leave to other countries. So, when that happens, what will happen to the Palestinians who are here for 70 years?”

Since President Donald Trump announced that the US was pulling its funding for UNRWA in August, services are now at risk. The US supplied about a quarter of UNRWA’s funding and without it, the agency may cut or drastically diminish some of its programs.

Related: UN agency chief says Palestinian refugees can’t ‘simply be wished away’

Habib desperately wants visitors to witness their reality — and help:

“The helping doesn’t need to be financial only. They can be teachers, they can be doctors since we don’t have a clinic, they can be there for specific programs — especially programs for women that teach them how to survive. … I’m trying to help build a community and just get support from outside.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?