Meet the man who volunteered for Obama, worked for Bernie and is now consulting Putin’s opponent

Vitali Shkliarov was mesmerized by Barack Obama's Berlin speech in 2008. Shkliarov went on to work for Obama and then Bernie Sanders. Now, he's a political consultant for the candidate permitted to run against Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In the summer of 2008, nearly 10 years ago, a certain junior senator from Illinois arrived in Berlin to a rock star reception. Barack Obama — still early in his bid for the White House — was seemingly as surprised as anyone by the crowd of nearly a quarter million that turned out to hear him speak.

Somewhere among the throngs that day was Vitali Shkliarov, a native of Belarus who had moved to Germany to study.

Related: US grand jury indicts 13 Russian nationals in election meddling probe

Shkliarov says he was mesmerized by the Democratic presidential nominee — or as mesmerized as he could be given that he didn’t understand a single word. At the time, Shkliarov didn't speak English.

“Zero,” he says, laughing. “It was just optics. I didn’t even understand. I was just like, ‘Wow.’ I got infected.”

Shkliarov describes “a collision of worlds” in his head that day. Watching the charismatic rising star of the Democratic Party he couldn’t help but contrast Obama with the stodgy politicians he’d seen back home in Belarus and as a kid growing up in the Soviet Union.

Related: Russia reacts to the 'oligarch list'

“So, just imagine you grow up on some brainwashed, communist crap on TV. And then it’s like, 'What’s happening? Why does my country not have politicians or ideas like this?' It’s all Obama’s fault,” he jokes.

In other words, Shkliarov says, “Thanks, Obama.”

Inspired by that Berlin speech, Shkliarov eventually made his way to the US where he signed up as a volunteer for President Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign.

Related: Will Russia get involved in the 2018 elections?

It was a dream come true, Shkliarov says — or would have been if he hadn’t been stuck making “get out the vote” calls in a dank basement. And again, he ran into a familiar problem: Shkliarov’s English was better, but still shaky.

“I just simply didn’t understand what people were saying," he says, playing up a halting, exaggerated version of his accent at the time: "Sir, can you please repeat again? They were like, ‘Dude, where are you from?’”

Shkliarov says he felt like a Belarusian version of “Borat,” Sacha Baron Cohen’s fictional idiot hero from Kazakhstan.

Related: Russia's Navalny arrested as thousands protest upcoming presidential election

Only then something surprising started to happen. While making his pitch to undecided American voters, Shkliarov started telling them his story. It wasn’t smooth but it was genuine — and it worked.

“I grew up in a country where nobody asked us [how we felt about elections]. Nobody asked me what president I would love to elect or even who I am. Nobody cared,” says Shkliarov, recounting his pitch to US voters. “So don’t give me this crap about 'you don’t have time.' If you don’t have time today then how about tomorrow? And they’d say: ‘um, well, yes.’”

It was the kind of authenticity grassroots campaigns are made of.

Out of the basement, onto other campaigns

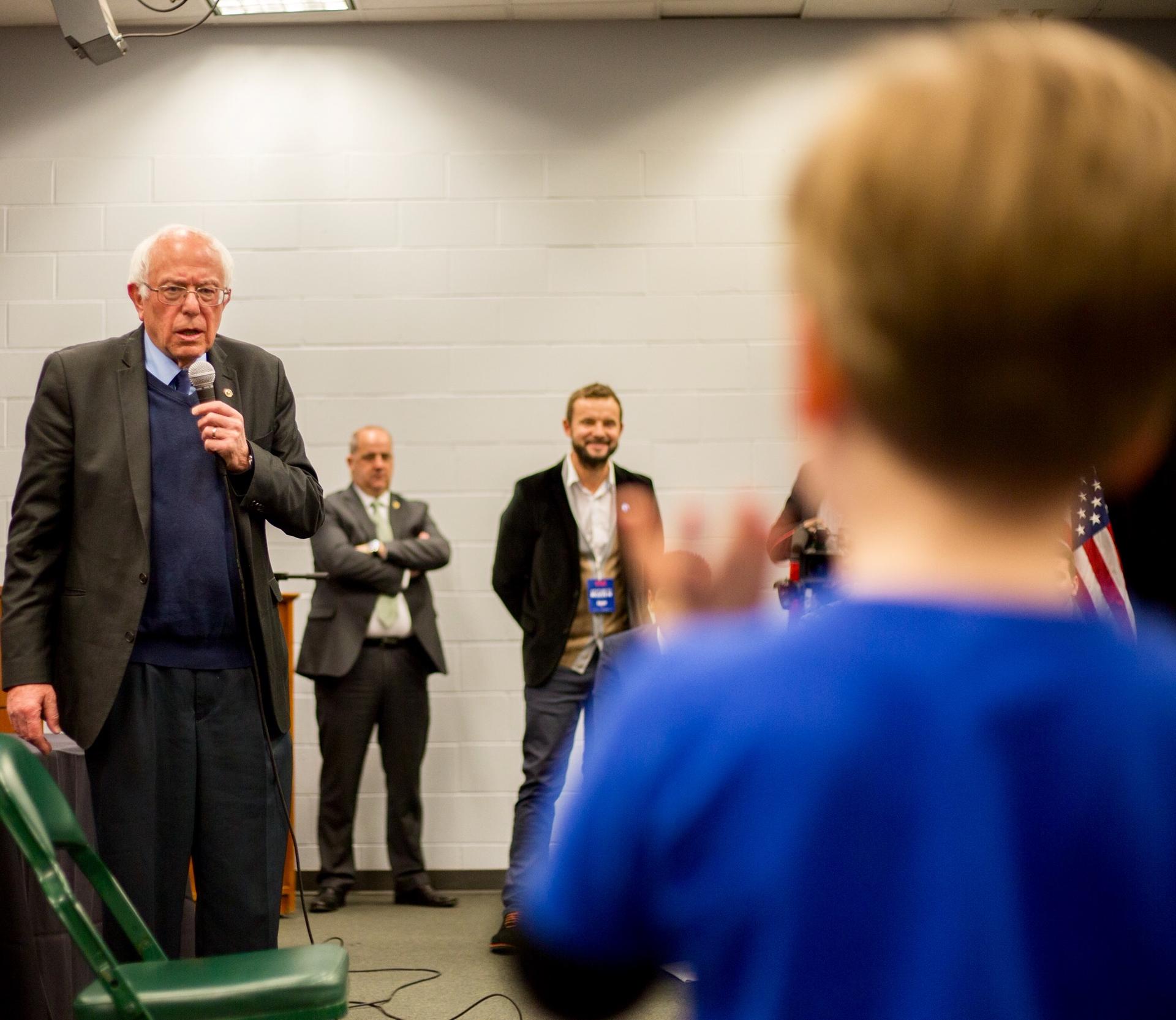

Soon Shkliarov was on his way, promoted out of the basement and — fast forward another election cycle — onto the frontline of yet another presidential bid: that of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

Shkliarov worked as a Sanders campaign staffer until Sanders lost the Democratic nomination to party favorite Hillary Clinton. Shkliarov says it was a disappointing loss but it taught him a hard lesson in politics.

“In the Bernie Sanders campaign, I was a bit idealistic. I said, 'Look, okay, if there is an ideal and perfect system on Earth that is democratic and set up to help people, it has to be the American system.' But then later I realized the money plays a huge role in politics.”

By this point, Shkliarov had become a skilled political operator with a sophisticated understanding of technology’s role in grassroots politicking.

Related: Young Russia, adrift from the Kremlin, stands up to Putin

That proved handy when in 2017 Moscow came calling. Russia’s beleaguered opposition, hoping to gain seats in municipal races, tapped Shkliarov to help build a creative tech-based campaign.

Sanders campaign strategy in Moscow

Shkliarov's approach was the so-called “Uberization” of Russian politics. He and a team developed online apps that allowed hundreds of opposition candidates — many of them newcomers to politics — to tack their way through Russia’s onerous election registration process. The result was surprise election night victories over pro-Kremlin candidates in several key districts.

Hardly a revolution, Shkliarov admits, but a promising sign for Russians who had lost faith in the electoral process.

Related: Russia agrees with Trump. The hacking investigation is a ‘witch hunt.’

And this brings us to the present and perhaps Shkliarov’s hardest assignment yet. He now serves as a key adviser to Russian-socialite-turned-presidential-candidate Ksenia Sobchak, who is making a long-shot bid for the Russian presidency in the country’s March elections.

Sobchak’s candidacy has been dogged by accusations that she’s a Kremlin-endorsed spoiler to generate voter interest. It’s understandable why: Current Russian President Vladimir Putin is widely expected to win outright — in part because the Russian leader’s fiercest critic, opposition leader Alexey Navalny, has been barred from the race. As a result, the Kremlin’s real concern now seems to be election turnout — getting enough Russians to legitimize the vote. Now, enter Sobchak’s sudden candidacy — or so the theory goes.

But Shkliarov rejects such spoiler charges. He says the important thing is that Sobchak is using her campaign to publicly challenge the Kremlin on a host of issues — including Navalny’s ban — that Russians would otherwise not hear about at all. This includes state television, where opposition candidates have traditionally had little or no access.

“This election is a fake, so in this type of reality you don’t have much of a choice,” Shkliarov says. “Even though you understand you’re going to lose, you can try to do something for a better future that will come, not on election day, but will come in maybe 20-30 years.”

Related: Moscow wags the dog on Manafort

And if that sounds slightly reminiscent of a phrase that Shkliarov’s political hero Barack Obama was known for — perhaps that’s no surprise.

“The arc of history is long but it bends towards justice,” Obama was often quoted saying — citing his own political hero, Martin Luther King Jr.

In the arc of Russian politics, Shkliarov admits he too, is a rare optimist. Is it "The Audacity of Hope" or utter delusion? Either way, Shkliarov says, “Thanks, Obama.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?