How a few notations by a school resource officer caused a teen to wind up in a high-security detention facility

Sheriff Thomas Hodgson, who runs the Bristol County Jail and built an immigration wing, takes ICE’s word that Henry Calderón is a gang member and a threat to the residents of Nantucket, and that’s why he’s locked up where he is. “It wouldn't make sense to put somebody in a situation like that where they would get targeted if they really weren't part of a gang."

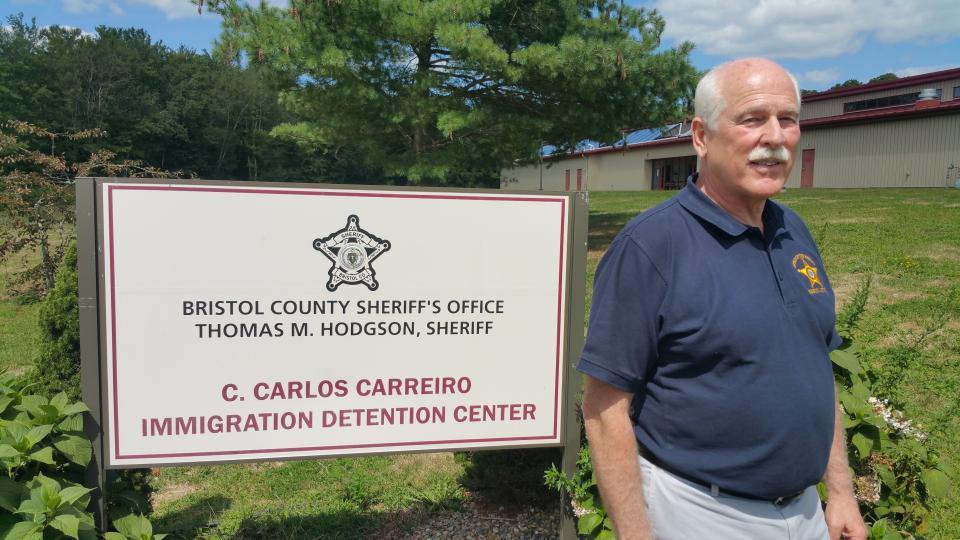

On the grounds of the Bristol County Jail in Dartmouth, Sheriff Thomas Hodgson took me on a tour of the immigration detention center built on his watch.

I was escorted into one of the wards for potential deportees, a low-security facility. Next door is another ward for higher security detainees.

“[In the higher security unit] are predominantly people who either have committed a crime or have had removal orders and didn't comply with the removal order,” Hodgson said.

Henry Lemus Calderón, 19, is incarcerated in this unit, and he can’t figure out why. Though in the country illegally, he was never arrested for any crime and never ordered removed, and he bristles at the notion of being considered in need of high security.

“I feel bad because I am not a gang member,” he said.

Gang member or not, how Calderón ended up in Bristol was the result of close cooperation between federal and local law enforcement, targeting suspected members of the MS-13 and 18th Street gangs on Nantucket.

His name appeared on a 2015 police report with the handwritten notation “18th Street gang member” submitted by an officer attached to Nantucket High School. In recent years, Central American gang recruiters were kicked off the high school campus, a law enforcement source confirmed. Police were increasingly worried about gang activity on the island and were keeping tabs on suspected members. Lt. Angus MacVicar of the Nantucket Police says the note about Calderón was entered into a database and shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“And with that shared information, ICE and other outside agencies have the ability to take a look at what's happened here and make a determination on whether or not, maybe, someone's illegal or not legally here in the country and then they would take actions on their own,” said MacVicar.

But ICE is not entirely on its own when its agents land on Nantucket. MacVicar acknowledged that his officers assist ICE agents.

"Our job is to make arrests and identify persons, in this instance, that could possibly be part of a gang," he said.

Massachusetts has a reputation as a relatively safe haven for undocumented immigrants. Since 2016, dozens of Central American families have made their way from Texas — known for its harsh immigration policies — to Massachusetts, with the help of volunteers and sanctuary communities, including those associated with the Needham Area Immigration Task Force.

But when it comes to suspected members of transnational gangs, especially MS-13 and 18th Street, many of these same municipalities cooperate closely with ICE, sharing information and coordinating operations. And that’s what's happening on Nantucket.

Local cooperation, explained ICE's Matthew Etre, is “really key to being successful in gang enforcement because the local authorities are the practitioners in their communities. They know exactly where the trouble spots are, who the individuals are that are causing that trouble.”

Etre, until recently, directed Homeland Security Investigations for ICE in New England. He said that the Nantucket operations that nabbed Calderón and other accused gang members over the past year were not indiscriminate.

“We have targeted operations," Etre said. "We identify where the individuals live ahead of time. We have surveillance and we try to take them into custody in the most safe and secure fashion, without creating a lot of issues within a particular neighborhood.”

Some Salvadoran workers on the island, seeking to protect themselves and their community from extortion and potential violence, have cooperated — such as Isidro Lemus.

“I know how dangerous these guys are, so if I see a little movement of gang members, first thing I will do is I will report it to the police department,” Lemus said.

His brother, Rodolfo, said ICE agents have continued to conduct raids on the island since the arrest of their nephew, Henry Lemus Calderón, in May 2016. One took place recently, he said: “They get a couple of kids, but these are no good kids. They are the gang members.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts wants to be sure they are truly gang members. Kade Crockford, who heads the ACLU's Technology for Liberty Program, accuses ICE of scooping up innocent young men. She calls it “a school-to-deportation pipeline.” The ACLU is pursuing a case in Boston similar to Calderón’s.

“A school resource officer witnessed a fight and wrote in the police report about not only the students who were directly involved in the fight but also about some of the students who were standing nearby, using extremely problematic generalizations," Crockford said. "[He] categorized one young man, who happened to be just standing near there, as a gang member.”

As in Nantucket, Crockford says that information was shared with ICE.

“This young man turns out to have been undocumented, and was — based on that information — seized and put into deportation proceedings because of this Boston police policy that allows the BPD to share that type of information with the federal government, even absent any evidence of wrongdoing,” she said.

But ICE spokesman Shawn Neudauer argued that being in the country without papers is wrongdoing enough. He acknowledged that the fears of the undocumented are well-founded.

“We might arrest someone who we’ve encountered while we’re looking for another person. While we may prioritize an MS-13 gang member, we’re not going to ignore people who have committed very few or no crimes whatsoever, but are still in this country illegally,” Neudauer said.

That practice worries undocumented immigrants on Nantucket and elsewhere. Rodolfo Lemus, for one, is rethinking his family’s cooperation with Nantucket police because of the coordinated ICE operation that landed his nephew in detention. Lemus, a US citizen, says his undocumented friends on the island — janitors, painters, carpenters and other workers — have also become less willing to cooperate with police.

“Before, ICE, when they come here, they are looking for one guy," Lemus said. "He’s a bad guy, you know. ICE said, 'Don’t worry, they're coming only for one guy.' And now, it’s changed everything."

This story, first published by WGBH News, is part two of a four-part series. Listen to part one. Check back later this week for future installments. Listen to the audio above to hear reporter Phillip Martin discuss his special report with Marco Werman of PRI's The World.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?