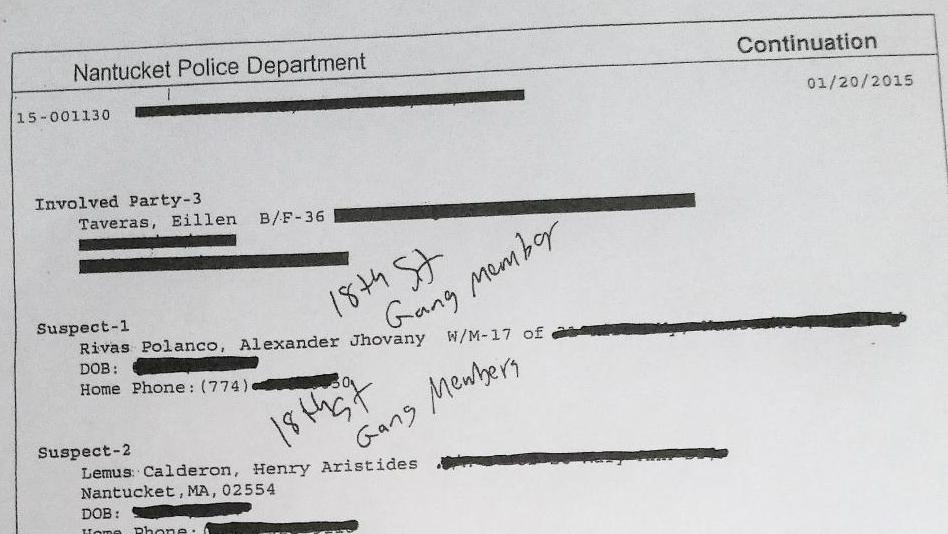

Handwritten notations on a school resource officer's police report tagged Lemus as a member of the 18th Street gang.

Henry Lemus Calderón was, by his own admission, not perfect.

He attended services at Faro de Luz church in Nantucket where the Rev. Rigoberto Lemus presides. Lemus — a common Salvadoran name on Nantucket and no relation to Henry — said Calderón spent a lot of time behind church doors.

“We'd have a service Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday, and he always came those days. He always [volunteered] to open the door, receive the brothers and sisters. And he’s a good person,” said Lemus.

Calderón’s family said he fled El Salvador after 18th Street gang members demanded monthly payments in exchange for his life. His brother-in-law was murdered in 2012 under circumstances that are not entirely clear, but the family was taking no chances. Calderón crossed the US-Mexico border on foot in early 2014 to escape gang violence, along with thousands of other unaccompanied minors. The Obama administration allowed some to stay if they had a sponsor. Calderón’s uncle, Rodolfo Lemus, lived on Nantucket, and soon the teen joined him and was enrolled at Nantucket High School.

By all accounts, Calderón was a good student, excelling in algebra. “He won excellence awards in his first few months of being here. And he barely spoke English, and he was already doing so well in school,” said Jocelyn Ramírez, his cousin.

But eventually, something went wrong.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents scooped up Calderón last year during an anti-gang operation on Nantucket, and he now sits in a detention center awaiting possible deportation to El Salvador. Calderón's supporters say ICE is trumping up charges and using the threat of gangs to sweep up undocumented young men from Central America. ICE already knew he was in the country and knew exactly where he lived.

A year after arriving in Nantucket, a police report written by a school resource officer tagged Calderón as a member of the notorious 18th Street gang. He was accused of threatening to beat up another student, a self-identified member of MS-13. Calderón was also alleged to have marked the school bathroom with the words La mara nunca muere, which means, "The gang never dies." But Zoila Gómez, Calderón’s attorney, said this and other conclusions reached by the school were based on a limited understanding of what determines gang membership.

“There are certain things you have to do," Gómez said. "There's certain things that they expect you to go through to become a member in order to be recognized and respected as a so-called member of a gang."

Gómez points out that Calderón was never arrested for any crime on Nantucket. And she said her client neither dresses like a gang member nor has gang tattoos. But Chris Cronin, who heads up ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations program in New England, said traditional gang markers have changed.

“In the past there would be tattoos that, you know, were overt and everybody could see them if somebody was wearing a T-shirt," he said.

Cronin said Central American gangs — including those on Nantucket — have resorted to more subtle ways of demonstrating membership. “It is challenging identifying folks that are part of gangs in today's world," he said.

Lt. Angus MacVicar of the Nantucket police says it's simple: “If they're going to go ahead and identify themselves, then we're going to treat them as that.” And, according to the police, several young men at Nantucket High School did just that.

But that's problematic, said attorney Lisa Thurau, who leads Strategies for Youth, which focuses on improving police-youth relations. She says by that standard, what might ordinarily be written off as teenage bravado is given life-altering consequences.

“On Nantucket, you have a perfect storm of school resource officers having to address normative behaviors of youth intersecting with Homeland Security investigations, which has the agenda of trying to rid this country of people they see [as] undesirable. And it appears that the lines aren’t clear about what level of proof is necessary," Thurau said.

Nantucket police vehemently deny any suggestion that its officers engage in ethnic profiling. But one resident, Fernando Ramos, said undocumented Salvadoran youth are painted with broader brushstrokes than other students at the high school. Ramos, a US citizen, and Calderón ate lunch together in the cafeteria. Ramos is convinced the gang label attached to Calderón is based in part on observing Central Americans hanging out together.

“Many white people are with their white groups and Hispanics with the Hispanics. In his case, he didn't speak any English. And he straight out came from El Salvador,” Ramos said. “Obviously, kids are going to see him as different.”

Several local residents, including a teacher and an artist, filed affidavits on behalf of Calderón. Nantucket resident Daniel Gault, a property manager, also vouched for him.

“We were putting in a generator and we had to dig about a 30-foot trench. And so, I brought him and his buddy, and the two of them came along and they put their heads down and worked,” Gault said. "You know, I've hired my neighbor. He's a local white kid and he's a terrible worker."

Gault said he was shocked to hear that Calderón was taken away by ICE. He’s being held in a section of the Bristol County Jail reserved for hard-core members of MS-13 and 18th Street gangs. Calderón’s uncle and guardian, Isidro Lemus, worries about his safety.

“He got involved in a fight with a gang member the other day because they say that he didn't want to go with them outside," Isidro Lemus said. "And Henry was like, ‘Listen, I'm not part of this whole thing. I'm here because they're accusing me of being with you guys.’ So he’s like, 'No way I'm going to get involved. I’d rather die before I do something stupid like that.'”

But Sheriff Thomas Hodgson, who runs the Bristol County Jail, takes ICE’s word that Calderón is a gang member and a threat to the residents of Nantucket.

“It wouldn't make sense to put somebody in a situation like that where they would get targeted if they really weren't part of a gang,” Hodgson said.

This story, first published by WGBH News, is part one of a four-part series. Check back all this week for future installments. Listen to the audio above to hear reporter Phillip Martin discuss his special report with Marco Werman of PRI's The World.