Is daylight saving time worth the trouble? Research says no.

Peter Shugrue checks one of four clocks destined for installation in Kansas City, Missouri, at the Electric Time Company factory in Medfield, Massachusetts, on March 8, 2013.

Today the sun is shining during my commute home from work. But this weekend, public service announcements will remind us to “fall back,” ending daylight saving time by setting our clocks an hour earlier on Sunday, Nov. 5. On Nov. 6, many of us will commute home in the dark.

This semiannual ritual shifts our rhythms and temporarily makes us groggy at times when we normally feel alert. Moreover, many Americans are confused about why we spring forward in March and fall back in November, and whether it is worth the trouble.

The practice of resetting clocks is not designed for farmers, whose plows follow the sun regardless of what time clocks say it is. And it does not create extra daylight — it simply shifts when the sun rises and sets relative to society’s regular schedule and routines.

The key question is how people respond to this enforced shift. Most people have to be at work at a certain time — say, 8:30 a.m. — and if that time comes an hour earlier, they simply get up an hour earlier. The effect on society is another question. Here, the research shows that daylight saving time is more burden than boon.

No energy savings

Benjamin Franklin was one of the first thinkers to endorse the idea of making better use of daylight. Although he lived well before the invention of light bulbs, Franklin observed that people who slept past sunrise wasted more candles later in the evening. He also whimsically suggested the first policy fixes to encourage energy conservation: firing cannons at dawn as public alarm clocks, and fining homeowners who put up window shutters.

To this day, our laws equate daylight saving with energy conservation. However, recent research suggests that it actually increases energy use.

The largest effects occurred in the summer — when shifting clocks forward aligns our lives with the hottest part of the day, so that people tend to use more air conditioning — and late fall, when we wake up in a cold dark house and use more heating, with no reduction in lighting needs.

Other studies corroborate these findings. Research in Australia and in the United States shows that daylight saving time does not decrease total energy use. However, it does smooth out peaks and valleys in energy demand throughout the day, as people at home use more electricity in the morning and less during the afternoon. Though people still use more electricity, shifting the timing reduces average costs to deliver energy because not everyone demands it during typical peak usage periods.

Other outcomes are mixed

Daylight saving time proponents also argue that changing times provides more hours for afternoon recreation and reduces crime rates. The best time for recreation is a matter of preference. However, there is better evidence on crime rates: Fewer muggings and sexual assaults occur during daylight saving time months because fewer potential victims are out after dark.

Overall, net benefits from these three durational effects of crime, recreation and energy use – that is, impacts that last for the duration of the time change – are murky.

Other consequences of daylight saving time are ephemeral. I think of them as bookend effects, since they occur when we change our clocks.

When we “spring forward” in March we lose an hour, which comes disproportionately from resting hours rather than wakeful time. Therefore, many problems associated with springing forward stem from sleep deprivation. With less rest, people make more mistakes, which appear to cause more traffic accidents and workplace injuries, lower workplace productivity due to cyberloafing and poorer stock market trading.

Even when we gain that hour back in the fall, we must readjust our routines over several days because the sun and our alarm clocks feel out of synchronization, much like jet lag. Some impacts are serious: During bookend weeks, children in higher latitudes go to school in the dark, which increases the risk of pedestrian casualties. Dark commutes are so problematic for pedestrians that New York City is repeating the “Dusk and Darkness” safety campaign that it launched in 2016. And heart attacks increase after the spring time shift – it is thought because of lack of sleep — but decrease to a lesser extent after the fall shift. Collectively, these bookend effects represent net costs and strong arguments against retaining daylight saving time.

Pick your own time zone?

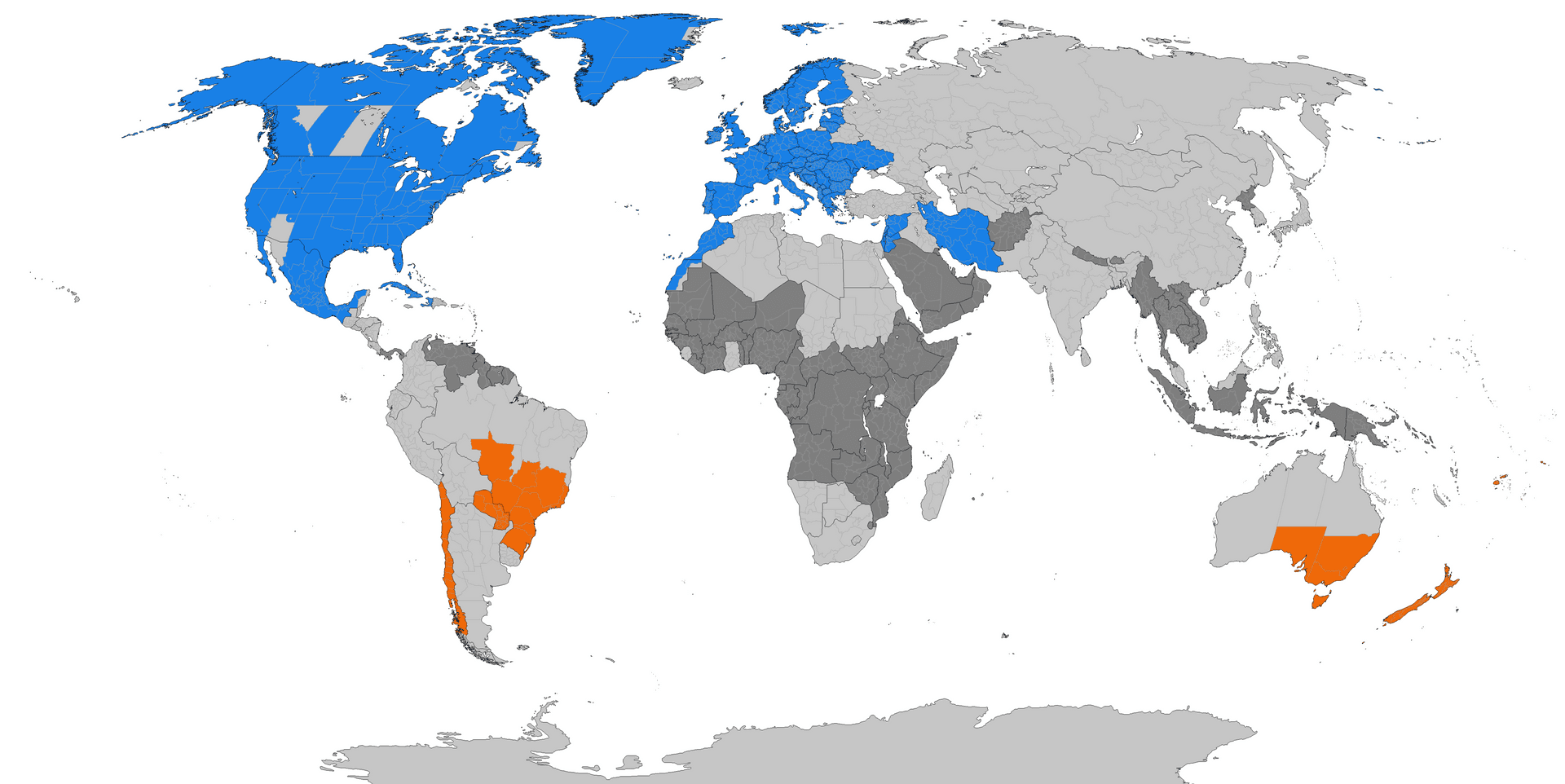

Spurred by many of these arguments, at least 16 states have considered changes to daylight saving time this year. Some bills would end daylight saving time, while others would make it permanent. For example, Massachusetts is studying whether to move in coordination with other New England states to Atlantic Time, joining Canada’s Maritime provinces one hour ahead of Eastern Standard Time. If they shift, travelers flying from Los Angeles to Boston would cross five time zones.

Some states have good reason for diverging from the norm. Notably, Hawaii does not practice daylight saving time because it is much closer to the equator than the rest of the nation, so its daylight hours barely change throughout the year. Arizona is the sole contiguous state that abstains from daylight saving time, citing its extreme summer temperatures. Although this disparity causes confusion for western travelers, the state’s residents have not changed clocks’ times for over 40 years.

In my research I have found that everyone has strong opinions about daylight saving time. Many people welcome the shift in March as a signal of spring. Others like the coordinated availability of daylight after work. Dissenters, including farmers, curse their loss of quiet morning hours.

When the evidence about costs and benefits is mixed but we need to make coordinated choices, how should we make decisions? The strongest arguments, with the exception of energy costs, support not only doing away with the switches but keeping the nation on daylight saving time year-round. This provides the benefits of after- work sun without the schedule disruptions. Yet humans adapt. If we abandon the twice-yearly switch, we may eventually slide back into old routines and habits of sleeping in during daylight. Daylight saving time is the coordinated alarm to wake us up a bit earlier in the summer and get us out of work with more sunshine.

Laura Grant, assistant professor of economics, Claremont McKenna College.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Nov. 2, 2016, on The Conversation. Read the original article.