In the shadow of a racist past, Portland still struggles to be welcoming to all its residents

A 1923 Ku Klux Klan parade in Albany is pictured. Oregon claimed the largest KKK membership of any Western state, with branches in every part of the state by 1925.

What happened on a Portland light rail train on an afternoon in May was stunning in its cruelty. Because of all the horrible things that have happened since, maybe you’ve forgotten — or maybe it’s stuck with you, for the very same reason.

About 4:30 p.m. on May 26, two young black women, one wearing a hijab, were riding the train when they were threatened by a white man yelling insults. Two other white men intervened, then the guy threatening the women fatally stabbed the other men.

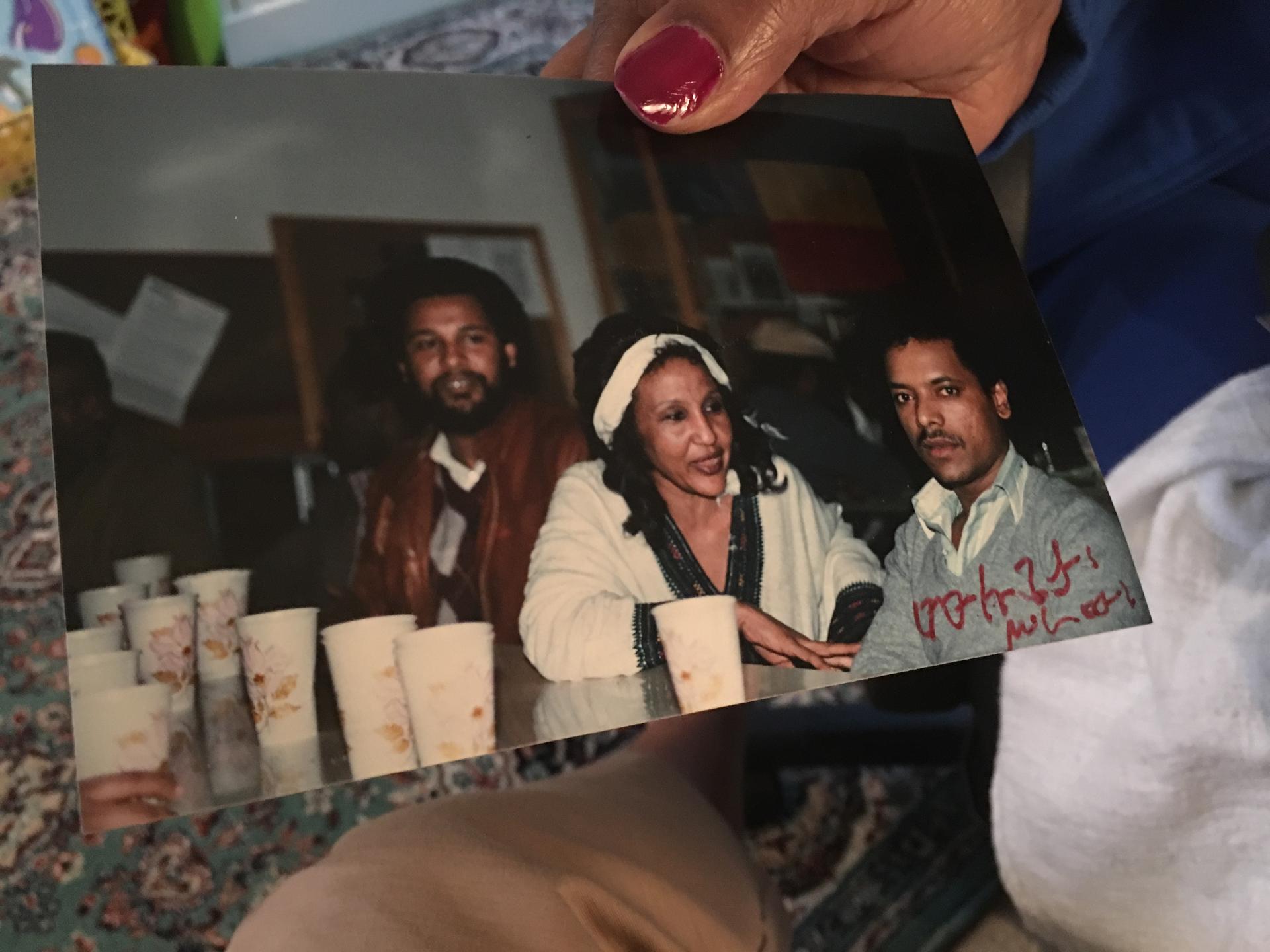

“I was heartbroken,” remembers Endeyu Kendie. She was just down the street at her office when the murders happened. “Those people. They were trying to defend somebody. And to be taken that way was so — I don’t know. So savage.”

People called the light rail murders a wake-up call, but Portland’s had wake-up calls before. Many of the city’s older activists said the murders made them remember the first wake-up call, nearly 30 years ago, and wonder if they had done enough.

Mulugeta Seraw was 28 and worked at a car rental place out at the airport. He was killed by members of the White Aryan Nation.

Kendie was just down the street from that incident, too.

“I was in bed sleeping,” she says. “It was early in the morning”

Her young son was asleep too, when someone knocked frantically. It was a guy who lived a few streets away, whom Kendie knew because they were both part of the tiny, close-knit Ethiopian community in Portland. She followed him outside and saw a pool of blood in the street.

That night, Kendie went to the hospital to find out what happened to him. They asked her to identify his body.

“His head was blown, his whole body was blown up. It was like — it’s like a dream even still when I think about it, that day,” she says. “It didn’t feel real.”

It took a while for Kendie to realize that what happened to Seraw had a particular significance in America, because he was black.

“Losing Mulugeta was sad, but when it got big like that, it was something unexpected,” Kendie says.

There were anti-hate protests and rallies and speeches and community meetings. Seraw became a symbol for people who identified with him, like Scot Nakagawa.

“It felt incredibly personal to me,” he says. “I felt as if I was in danger.”

Nakagawa was a young college dropout from Hawaii, of Japanese descent. He worked at a homeless nonprofit and had been chased home by a truckload of white men who pummeled him with beer cans.

“Portland police said there were no neo-Nazi skinhead groups here in Portland. There were no neo-Nazi activists. And we saw them,” Nakagawa says. “We saw them around us. They were in our faces.”

Nakagawa joined a band of young activists who, by night, infiltrated Portland’s blossoming punk rock scene, where white supremacist groups were trying to recruit. By day, the activists organized out of an old warehouse they called the Matrix. There were squatters living in one corner and in the other, an old printing press once used by Portland radicals.

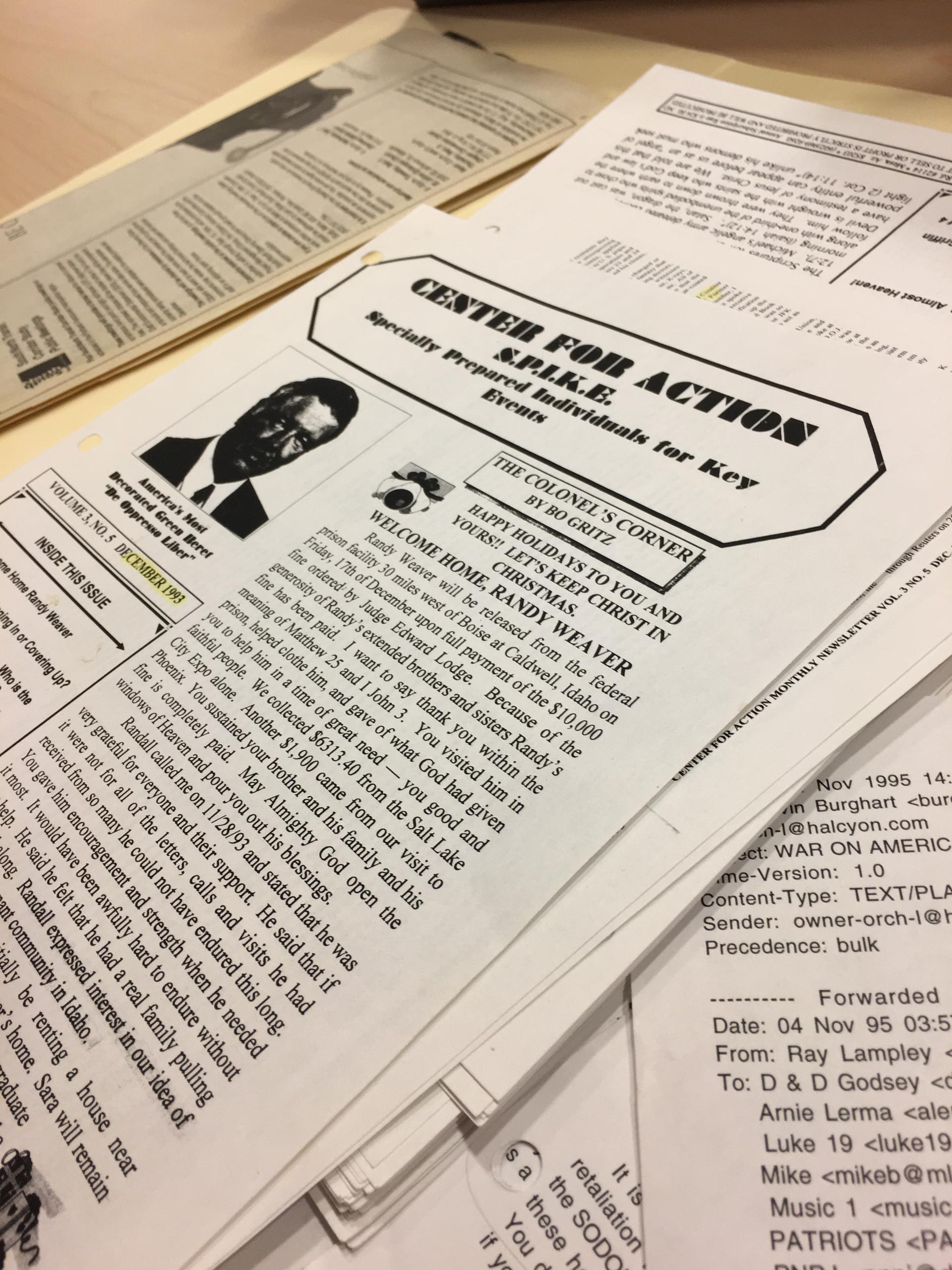

They were part of an unprecedented network of Portland groups that called itself the Coalition to Protect Human Dignity. Together they amassed evidence, including white supremacist newsletters and magazines, to prove to police that white hate groups were a threat in Portland.

Jewish studies professor Steven Wasserstrom was a coalition board member, and one of the group’s public faces. White supremacist leaders published his name and address, and Wasserstrom received graphic, violent threats. He went to the police, who advised him to get a dog.

“I’m supposed to go home and tell my wife and these two small children that these Nazis have threatened us. They know where we live. I’m a public figure — and I should get a dog,” he says. “So that didn’t feel like making me much more secure.”

“When we would call the police they would often take a long time to show up. You know I think because they just felt like these are people who are trying to look for a fight,” Nakagawa says. “I think briefly we were regarded, some of us, as gang members — you know, anti-racist gang members.”

Police don’t remember it like that. When I asked what it was like back then, Sgt. Chris Burley, the Portland Police Department’s public information officer, called the detective who investigated Seraw’s murder for a firsthand account.

“The city recognized that there was an immediate issue that was coming about involving hate groups,” Burley says.

From the police point of view, there was an overwhelming response. Oregon passed a landmark hate crimes statute. Police found Seraw’s killers and the men were convicted. Then the founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, Alabama civil rights attorney Morris Dees, came to town with a novel new strategy: Drain resources from hate groups by suing them.

Dees sued California KKK grand dragon Tom Metzger, arguing Metzger incited the men who killed Seraw. Dees won, and Metzger was ordered to pay $12 million — at that time the most ever awarded in a hate case. Burley says police protected the judge, jury and Seraw’s family around the clock during the trial.

But as for tracking white hate groups in general, Burley says police can only investigate if a crime’s been committed. So the bureau couldn’t always do what activists wanted.

“As law enforcement officials, we might find the words offensive, but so much of the time what people say is protected by the first amendment,” he says.

Things changed suddenly in 1995, when Timothy McVeigh bombed the Oklahoma City Federal Building. The FBI made white hate groups a priority. Nakagawa says within a decade there was a perception the problem had been addressed. Funding for anti-hate groups slowed. The Coalition for Human Dignity collapsed. Nakagawa and other activists moved on to other organizations and other causes.

Fast forward to May 25 of this year — the day before that deadly attack on the train. An African American woman named Demetria Hester was also on a light rail train, headed home from her job as a chef. A white man started yelling racial slurs. She asked him to stop, and he threatened her.

“It was 25 to 50 people on that train that did nothing,” she said.

Hester got off the train. The man followed her and hit her in the eye with a gatorade bottle. Hester maced him. She told a police officer what happened, but police couldn’t find the man who had threatened her.

Police say her attacker was Jeremy Christian. The next day, he got on the same train line and, by his own admission, committed the murders that put a national spotlight on Portland once again.

“I should feel safe in Portland,” Hester said at the conference. “I don’t.”

Looking back, Nakagawa thinks what he and other activists did after Seraw’s murder was important, and had an impact. But he says they failed to be vigilant, and now it feels like they’re starting from scratch.

“We should have been more attentive,” he says. “But this is a story of America, isn’t it. We’ve done this over and over and over again this is not the first or the second or the third time.”

‘Have we done enough? Absolutely not’

On the day of the light rail murders, Portland’s mayor was on a flight to London, so Chloe Eudaly, the chairwoman of the city commission, was the face of the government. An independent bookseller, she’d been elected to the commission just five months before.

“Honestly I was out with a friend, just kind of decompressing after work when my phone started ringing,” she recalls. “From her little convertible in Cathedral Park, I was talking to people on two different phones.”

In Portland four commissioners and the mayor directly run the city — there’s no city administrator. It’s the last big city in America to do things that way, and critics say that has kept the city commission from becoming more diverse. Eudaly’s white, but she was elected from a more diverse area of the city.

“Progressiveness coupled with a lack of diversity is one of our problems,” she says. “I think the majority of the white residents here have been blissfully unaware of how hostile the city can be to people of color and other marginalized groups.”

She says that’s because few white residents are exposed to people of color — Portland’s the whitest big city in America. After the murders, there were vigils and community meetings, but the city council’s principal response was a one-time allocation of $350,000 to fund anti-hate programs. Eudaly’s staff had recommended city commissioners allocate more than $2 milion.

“Have we done enough? Absolutely not,” Eudaly says. “But have we made progress in the right direction? Yes. I mean we are having conversations now about our city that were not happening on any kind of large scale 15, 20, 30 years ago.”

But those are small steps to undo more than a hundred years of history. The state’s original constitution banned black people. It was illegal for African Americans to move into the state until the mid-1920s. And the KKK was an institution, says Randy Blazak, head of the Oregon Coalition Against Hate Crimes, a partnership of community groups and government agencies.

“We had a governor who was basically elected by the Klan. It was sort of that open,” he says.

The coalition gives bus tours of Portland’s racist past. They stop at the Portland Expo Center, where thousands of Japanese Americans lived before being shipped to federal incarceration camps during World War II. The tour visits the river bank where a mostly African American city was allowed to wash away in a flood after that war. There’s also a stop at the intersection where Seraw was beaten to death in 1988.

“We end up at a restaurant called Clyde’s Prime Rib that, in the ’40s, was called the Coon Chicken Inn. And it was a big caricature of an African American face as you walk through to get into the front door,” he says.

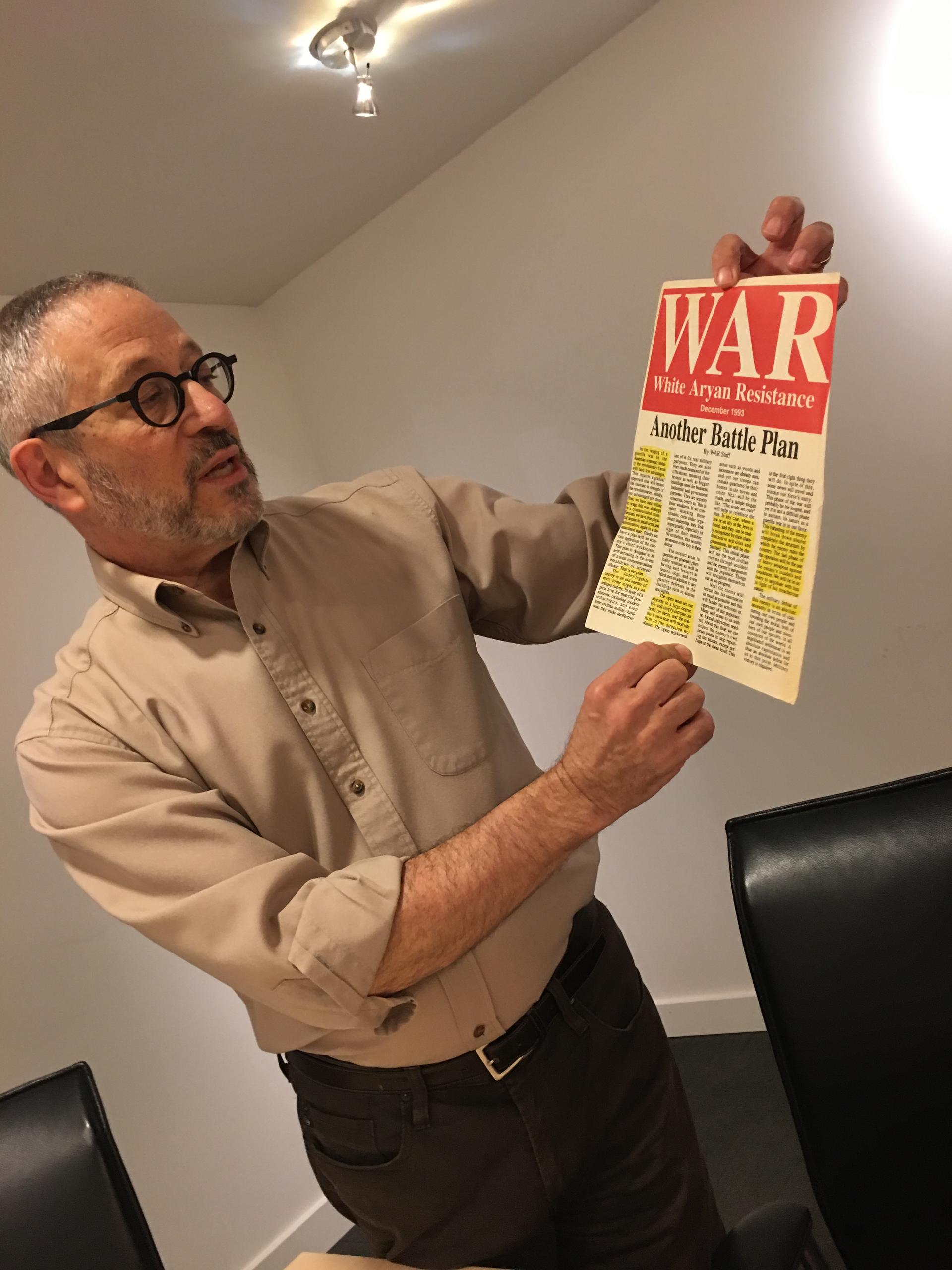

It was long gone by the time Blazak arrived in the 1990s. He was a young researcher, driven to study white supremacist groups after growing up white in what he describes as a Georgia Klan town.

“I was a kid who wrote an essay for my journalism class — we had to write an editorial — and my editorial was, ‘If they have Black History Month why don’t we have White History Month?'” Blazak says.

He’s been making up for doing things like that ever since, by trying to understand white hate groups. He says the white supremacist groups in Oregon now recruit a lot in prisons. But they’re less structured than in the past; there’s more of a leaderless resistance model, where people check in on websites instead of belonging to a formal organization. Blazak says that makes them harder to track and combat.

“We’ve often tried to encourage people to not use the notion of a white supremacist movement, because it’s not really moving anywhere and there’s a lot of tension and conflict within it. It’s more of a white supremacist counterculture,” he says. “It’s not really a kind of unified movement as much as what I think of as a bunch of knuckleheads.”

Representatives of the Portland anti-fascist group Rose City Antifa are trying to document and track the movements of those people Blazak calls “knuckleheads” — antifa says those white supremacists can’t be dismissed because they’re on a path of increasing violence. They point to Christian — the accused murderer of the two men on the light rail. A month before the deaths, he participated in a march where he was videotaped giving a Nazi Sieg Heil salute.

The organizer of that event, and many others up and down the West Coast, was Joey Gibson, a 33-year-old real estate investor who says he became an activist during the election.

“I realized that we have a big problem, culturally. We’re being trained to dehumanize people,” Gibson says. “All you have to do is say, ‘They’re racist,’ or say this or say that and then all of a sudden the mob comes out of nowhere and tries to justify assaulting you — dehumanizing you.”

Gibson’s half Japanese, half white. He says he’s not a white supremacist, and he denounces them. His purpose, he says, is to draw attention to violent people on the left, like antifa.

“I want to show liberals that that we are not the violent ones, we’re not the hateful ones, and you need to disavow and distance yourselves from these far-left, these alt-left protestors just like we have to distance ourselves from the alt-right,” he says.

Portland officials have tried to shut down at least one of Gibson’s rallies in the city, unsuccessfully. So they’ve adopted a broader strategy — to be vocal and consistent about condemning hate. On a recent Sunday, Mayor Ted Wheeler wore sneakers and a hoodie to address a few hundred people at a city rally in a downtown park. Leaves floated down on the audience of a few hundred mostly brown and black people.

“All of us who call this country home feel a responsibility to condemn racism, intolerance, hatred. The goal of all of which is to divide. To oppress,” Wheeler said.

Leaders vowed to combat hate and white supremacy as institutional problems, not just isolated incidents carried out by mentally unstable people. Local county chair Deborah Kafoury said she’d heard about discrimination from her own staff of color.

“We had a very painful and emotional and raw board meeting,” she told the crowd. “We heard from employees and the community how racism and oppression show up in our workplace. And we voted to pass the first equity workforce resolution in our county’s history.”

But many people of color I talked to remain skeptical. Like the Reverend Joseph Santos-Lyons of the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon, known as APANO. He’s Chinese American, and he also spoke at the rally, striking a very different tone from other speakers.

“We’re watching you,” he said. “I’m actually not here to validate your event. I think we at APANO will do our best to be partners when we can, and sometimes we’ll disagree. But what I do appreciate is you make space for us at the table. I think that’s a new tradition we need to continue.”

But the question now is how to get everyone on board with the new tradition, and the commitment to defy Portland’s racist past. Earlier this year the mayor put out an ad for a new police chief. The job description said Portland was looking for someone who could address the city’s history of legally enforced, systemic racism. And the police union president was offended. He said the mayor had angered and frustrated rank-and-file officers by disregarding decades of progress.

“The police bureau is a really tough nut to crack,” Eudaly says. “Councils have given away a lot of power. We have a very powerful police union. I appreciate the work the police do. I am supportive of them. I think it’s important for me to convey that I’m frustrated by certain issues we’re facing with our bureau and how hard it seems to make real change.”

Change not coming fast enough

On his desk in his office at the Portland police union, Daryl Turner keeps a picture of himself shaking hands with Barack Obama. It’s from when Obama was an Illinois senator.

“I went and took a picture with him, and he said, ‘Hey I really respect law enforcement and what you guys do,’” Turner remembers. “I said, ‘Hey, we’ve got some changes to make but yeah.’”

Turner played football at the University of Washington and joined Portland’s gang task force in the 1990s. Now he’s the first black president of the union. When the mayor put out that ad for a new police chief, Turner was the one who called him out. He says the mayor should’ve put the desire to fight racism in a more positive way.

“Although we have wounds that we need to heal, we need to heal those wounds and move forward to be stronger — although we have learned lessons from the past,” he says. “I think there’s always going to be some resistance to totally acknowledge, but that will be from people who don’t want to be part of the movement to move forward.”

That question of how the movement goes forward — it hangs in the air everywhere in Portland. On the one hand are people so radicalized they’re thinking about violence. On the other hand are people who’ve been fighting in the trenches for years, including two elder statesmen of local immigrant communities — Wajdi Said, president of the Muslim Educational Trust mosque and school, and Ronault “Polo” Catalani, the city’s immigrant integration advisor.

Said’s from Yemen. He came here as a college student. After the murders on the light rail, he helped raise thousands of dollars for the victims. Catalani’s family was expelled from Indonesia for being mestizo. Now he’s a lawyer. And he’s very open about how he’s gone around regular channels in order to get work done fast in Portland immigrant communities.

“We’re from countries where government has never been there for us,” Catalani says. “We go the other way when we see them.”

To get things done, Catalani and Said have partnered with community elders, civic activists and city workers to create community gardens, establish mobile playgrounds or just to get street lights installed.

“This is doing it, instead of talking about it,” Catalani says.

“Reality is that we have to be positive,” Said adds. “We cannot afford to be negative.”

Recently they’ve connected undocumented mothers with individual police officers they can trust not to share their information with federal authorities.

“We tell them don’t call 911,” Catalani says. “You call an officer who you’ve talked to. Who you have spent time with.”

Catalani and Said say this is how they’ve made progress — person by person, and slowly. That seemed to be enough until the presidential election, and until two men were murdered on the Portland light rail train. For people who don’t feel safe, who feel targeted, it’s tough to live in a city people think of as ultra liberal, because that doesn’t match the reality they’re experiencing.

“In Oregon, everybody will say the right things,” says Kayse Jama of the nonprofit organizing group Unite Oregon. “Yet, they actually do the wrong things, or they don’t do a lot.”

Jama, who is from Somalia, says people have protested outside Unite Oregon’s offices and covered their windows in anti-Islam pamphlets. At one of their events a few months ago, some men drove by waving replica guns. Other Muslims have told Jama about being harassed while driving.

“When they called the police, the police were treating the issue as some sort of road rage issue,” Jama says. Other Muslims told him they reported what happened — and never heard back.

When asked for a time he didn’t feel safe, Jama recalls a time getting on the highway with his family, when an intense conversation with his wife led him to let his foot get a little heavy on the pedal. He hears sirens, pulls over and their 7-year-old daughter has a panic attack. She starts crying uncontrollably because she thinks the police officer is going to hurt them.

“I actually tried to assure toward her. And I couldn’t do nothing. She wouldn’t believe me,” Jama says.

Later, Jama had this moment of clarity that summed up the situation. It was a few weeks after the murders on the light rail and groups Jama calls white supremacist were rallying in a downtown park. Jama was across the street, speaking in front of the doors to city hall.

“As I was speaking at the podium, I looked out and I was like, ‘Oh my goodness.’ Because immediately I saw law enforcement holding their clubs facing us. And the white supremacists were at their backs,” he remembers. “So I asked a question for myself: ‘Who are they protecting and who do they see as the problem?’”

Jama says he’s doing everything he can to change things fast — he’s running for state senate. To be fair, Portland police spokesman Burley says police want everyone to feel like they’re heard. He points to the bureau’s many advisory committees for marginalized groups. And he points to the new police chief, who started her job earlier this month — she’s the first African American woman to lead the bureau.

“The police bureau is learning about how we are perceived. And we want to be an agency that is trusted, that has legitimacy,” Burley says. “If it’s something that we cannot further investigate because it does not meet the definition of a crime, we want people to know that and we do have sorrow for those types of situations.”

Those reassurances aren’t enough for Gregory McKelvey, a 24-year-old political consultant about to finish his law degree, who grew up black in Portland and now heads one of Portland’s largest protest groups — PDX Resistance. The group has frequently taken to Portland streets in demonstrations that sometimes turned violent.

“I have to say, and I do say, that I don’t condone violence against people or property,” McKelvey says. “But, you know, I think that it’s a shame that we have a lot of people in Portland that maybe are more upset about broken windows than the people that are forced to sleep outside next to the shattered glass.”

McKelvey argues change isn’t coming fast enough — especially when the question of safety is real and urgent for people of color.

Catalini and Said say they know many people — especially millennials — are impatient for change.

“We’re aware of them and they’re aware of us,” Said says.

And Catalani adds, “They don’t seem to be able to understand — of course they cannot — that that plateau from which they are able to be this way is because we really suffered.”

A few minutes after making that point, though, Catalani reconsidered.

“I’m so proud of them because they’ve raised the level of expectation from our communities. Our level of expectation from white folks is fairly low, because we’ve never expected anything: ‘Never mind, I’ll fix that myself because you give me a headache and a stomachache and I will just get with my people and we’ll fix this. Never mind you,’” he says. “But now, each next generation is expecting Americans to give more, to do more, to be more.”

And, Catalani says, for this they are grateful.

A previous version of this story misspelled Gregory McKelvey’s name and misstated how Mulugeta Seraw was killed.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?