Patrons toast to the memory of Filipino bartender Ray Buhen at the Tiki-Ti in Los Angeles on Jul. 26, 2017. Buhen was the original owner of the famous bar. Legend has it that this place was the inspiration for the Mos Eisley Cantina in Star Wars.

It’s a warm summer evening and a crowd gathers in a small, divey bar on Sunset Boulevard just east of Hollywood. The place is packed and every inch is decorated with bright strings of light, tapa cloth and tropical knickknacks. Folks new to the bar and longtime patrons, some wearing Hawaiian shirts and holding their own unique mugs, sip strong cocktails.

Welcome to the Tiki-Ti, the oldest family-owned Tiki bar in Los Angeles, the birthplace of the Polynesian-inspired rum palaces that were all the rage in the 1940s through the 1960s.

Despite its retro reputation, Tiki culture is alive and well at the Tiki-Ti. A few dozen people gather to sip on tropical cocktails and take part in the weekly Wednesday night toast to the bar’s original owner, Ray Buhen.

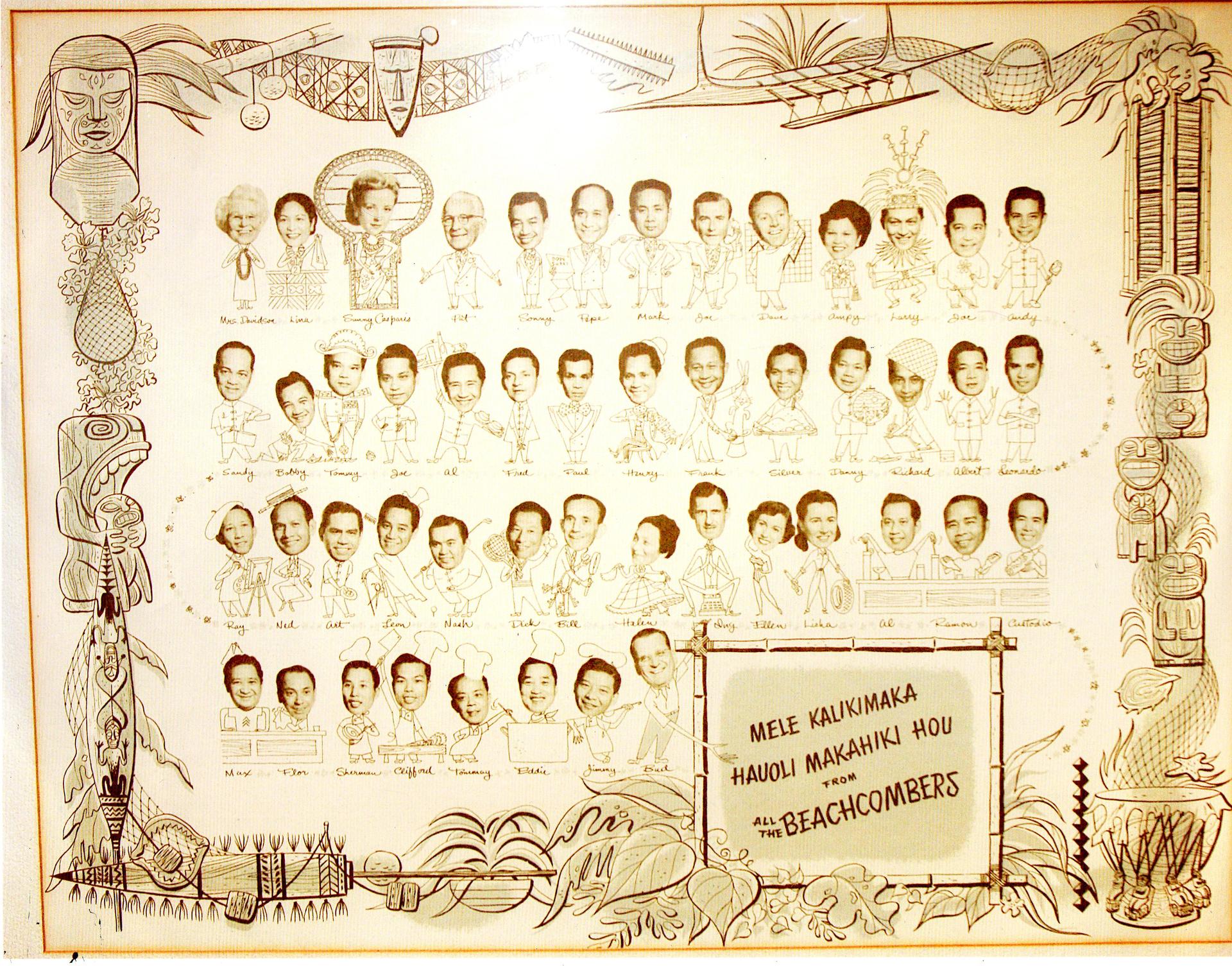

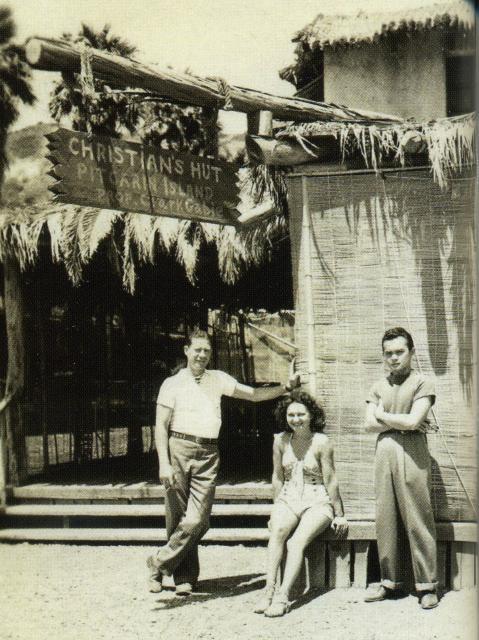

A legend in Los Angeles’ Tiki bar scene, Buhen was one of the original Filipino bartenders at Don the Beachcomber, the first Tiki bar that opened in Hollywood in 1934.

That bar was owned by a man who went by the name Donn Beach, but it was the Filipino bartenders who popularized its tropical cocktails.

“Filipinos back in the '30s and '40s, they made tropical drinks,” says Mike Buhen, Ray’s son, who owns and operates the Tiki-Ti today. “They all became waiters, bartenders, busboys. They were the backbone of tropical drinks at that time.”

Ray Buhen died just shy of his 90th birthday in 1999. Over the course of his career, he served Hollywood stars like Charlie Chaplin, Jean Harlow and Howard Hughes. He mixed drinks for a young Nicholas Cage and a budding director named George Lucas, who sipped on Tiki drinks while sketching characters for what would become “Star Wars.”

Mike says his father supposedly served as the inspiration for the character Yoda, and Tiki-Ti was the basis for the Mos Eisley Cantina, where Han Solo shot first.

But mixing tropical cocktails wasn’t Ray Buhen’s first calling. It was one of the few jobs open to people who looked like him.

Ray Buhen moved to Los Angeles from the Philippines in 1930 during a significant wave of Filipino immigration. Carina Monica Montoya, author of “Filipinos in Hollywood,” says her father was a waiter and bartender at Don the Beachcomber too. At the time, Filipinos came to America in search of opportunity, but were often met with racism, and ended up taking on farm or domestic work.

“My dad and Ray Buhen and others that chose to work in the cities, they found employment in some of the nice hotels and restaurants in Hollywood,” says Montoya.

Known as the generation of manongs, or uncles, Filipino men often banded together in “bachelor societies” and walked the streets in groups for protection. They congregated in Little Manila, an area in downtown Los Angeles now known as Little Tokyo.

More about the history of this neighborhood: African American laborers were housed in Little Tokyo during the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans.

When Ray Buhen first moved to LA, he worked as a bellhop at the Figueroa Hotel downtown before landing a promotion.

“He became the elevator guy,” Mike Buhen says. “He used to joke around [and say], ‘Hey I’m moving on up!’”

His next job took him to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where a manager sent him to bartending school in preparation for the end of Prohibition in 1933. When he finished, he applied for a job at Don the Beachcomber and the rest was history.

“All the great Tiki bartenders of the past were Filipinos, almost without exception,” says Jeff Berry, author of “The Grog Log” and owner of the New Orleans Tiki bar and restaurant Latitude 29.

Not only was Ray Buhen one of the original bar staff at Don the Beachcomber, Berry says, “he worked in just about every famous Tiki place over the years.”

As Tiki bars grew in popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, they evolved into massive themed restaurants serving exotic cocktails alongside faux Chinese food. Whether it was due to their Pacific origin or skills, Filipinos remained key figures in Tiki bars — at least until the end of their shifts.

“They couldn’t go [to the Tiki bars] for dinner or for drinks,” says Montoya. “They would go back to Little Manila — it was the impoverished section of the city — and that was it until the next day, come back to work.”

Montoya’s father left bartending to pursue other jobs, but passed away when she was a child. Before he died, he tried to assimilate himself into an American society that more often than not rejected his Filipino origin. He changed his name from Tomas to “Tommy” and dressed like Clark Gable. So did other manongs.

“[My father] really didn’t have anything, but projected that he did, which was very typical of the men of that era,” says Montoya. “My mother would always say that when he looked in the mirror, he didn’t see himself as Filipino.”

Mike Buhen says his father wanted to become so American that he changed his name from “Buhion” to “Buhen” because it sounded more Western. He never spoke Tagalog when he was out in public.

But Ray Buhen’s bartending talents helped him beat the odds stacked against him because of his race and the color of his skin. In 1961, he opened the Tiki-Ti. His wife, a white woman, and his son helped run the place.

“For a Filipino and Caucasian woman to marry and have a business together, that wasn’t a very good idea,” says Montoya. Anti-miscegenation laws made it hard for Filipino men and white women to marry, let alone start a business together.

But Ray Buhen’s talent for mixology preceded him. “He was such a great bartender and his drinks were famous in LA,” says Montoya.

Though the original Don the Beachcomber is long gone, Ray Buhen’s Tiki-Ti still stands today, still owned and operated by his family. The drink list includes classic recipes from Don the Beachcomber and Ray Buhen’s own concoctions, like the potent “Ray’s Mistake” and the “Chief Lapu-Lapu,” a citrus punch named after the first Filipino hero who resisted Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines.

These days, there has been some discussion about Tiki bars being fraught with complicated cultural issues including cultural appropriation and racism. Columnist Sarah Burke called the Tiki bar “one of American culture’s most enduring forms of escapism.” Tiki bars, she writes, “conveniently erase the South Pacific’s history of colonization and explicitly place the consumer in the role of the explorer.”

But still, they persist, and have even grown in popularity. While some newer Tiki bars attempt to be less kitschy and more authentic, most still harbor remnants of midcentury Tiki culture like the Tiki figure, which represents gods and ancestors in Polynesian culture, but is used in Tiki bars on mugs and decorations.

For Ray Buhen in the pre-civil rights era, Tiki bars were a means to survive and provide for his family. This was true for many Filipinos and people of color of the time, whose employment options were often limited to the service industry. Over the years the Tiki-Ti has developed a community among its customers, from the old regulars at the end of the bar to the young couple visiting for the first time to the psychobilly Mexican artist who shows off Tiki mugs he carved himself.

For Mike Buhen, maintaining his family’s Tiki tradition is all part of the job.

“I’ve been around this all my life. I grew up in, you know, booze, bars and all this stuff because my dad did it,” he says. “My dad bartended [for] 60 years. I’ve been doing this for 46 years now.”

A picture of Ray Buhen still hangs on the back wall of his bar. And every Wednesday night at 9 pm, his son leads patrons in a toast to his legacy, a reminder of the little-known Filipino history of Tiki bars.

Find more of reporter Paola Mardo’s work on Tiki bars and culture at Ampersand.