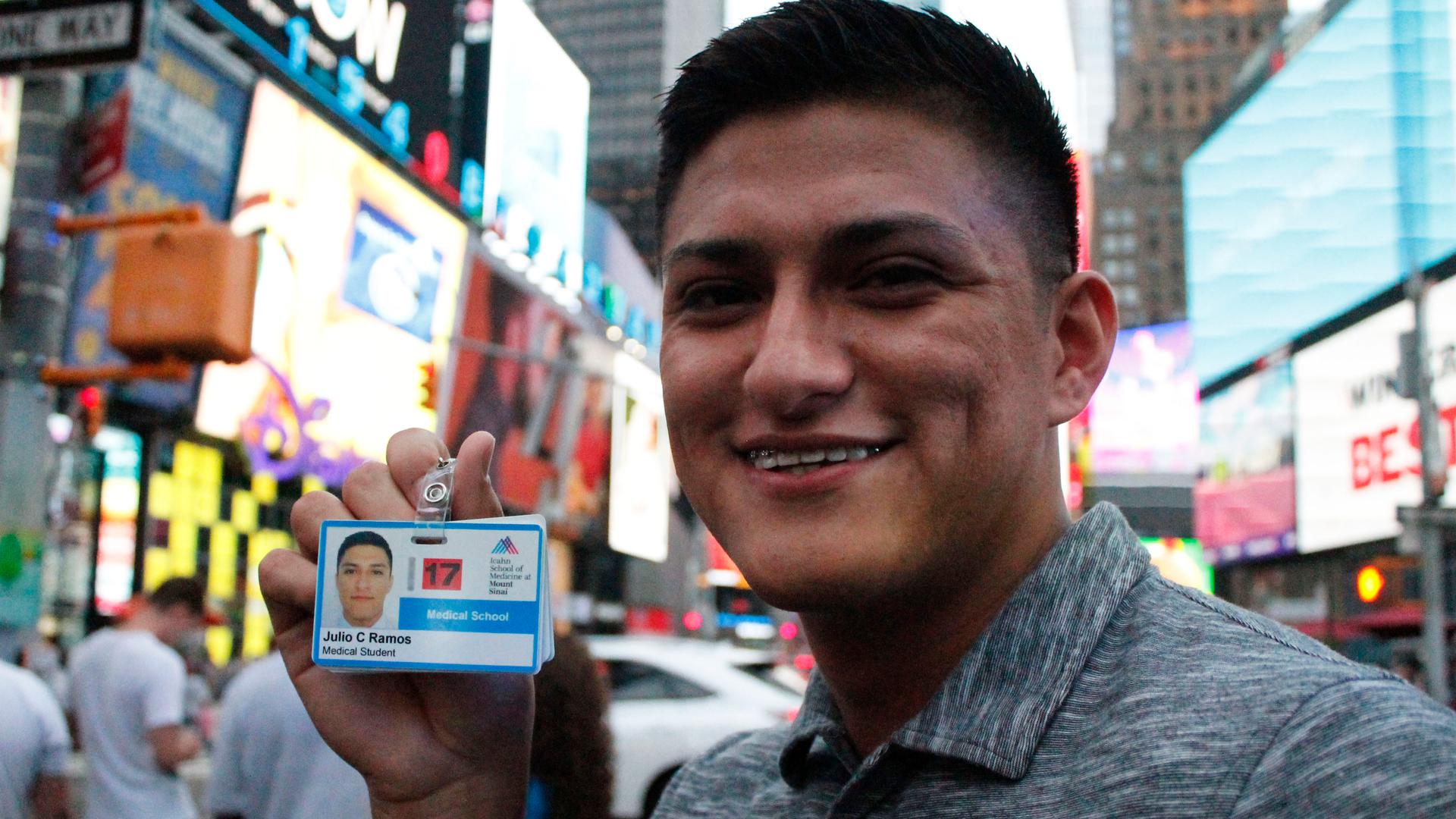

Julio Ramos, from the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, just began his training to become a medical doctor in August 2017. He moved to New York to begin school — and is among almost 800,000 people who have work authorization through a program for immigrants who were brought to the US illegally as children.

In the months before President Donald Trump announced his decision to end DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, Julio Ramos had been getting ready to move ahead in life.

Ramos, 24, is undocumented and a DACA recipient. And with that status, he began his training to become a physician at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. He is among almost 800,000 people brought to the US illegally as children, who have been granted two-year work permits and reprieves from deportation as part of the Obama-era program.

US Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced Tuesday that the program would be shut down. In a press release, the Department of Homeland Security, which would oversee the “wind down” of DACA, said it would stop renewing the status for current beneficiaries in about six months.

“With the measures the Department is putting in place today, no current beneficiaries will be impacted before March 5, 2018, nearly six months from now, so Congress can have time to deliver on appropriate legislative solutions,” DHS acting director Elaine Duke said in the statement. “However, I want to be clear that no new initial requests or associated applications filed after today will be acted on.”

DHS said that anyone whose status expires before March 5 can apply for a two-year renewal by Oct. 5. Applications that have already been received will be reviewed as before, on a case-by-case basis.

Sessions said Americans have rejected an “open-door [immigration] policy” and said that enforcing laws does not mean the country is disrespecting immigrants. The DACA program, he said, was an executive overreach by President Barack Obama and shows “disrespect for the legislative process.”

Sessions took no questions after his statement.

Immigrants and their advocates are concerned that, if the status of DACA recipients is allowed to expire, they will become a priority to be removed from the US. In a statement, Trump said he will continue the policy of prioritizing pursuing criminals for immigration enforcement.

“Our enforcement priorities remain unchanged, he said. “We are focused on criminals, security threats, recent border-crossers, visa overstays, and repeat violators. I have advised the Department of Homeland Security that DACA recipients are not enforcement priorities unless they are criminals, are involved in criminal activity, or are members of a gang.”

But arrests of immigrants with no criminal records almost doubled in the first weeks of the Trump administration. Several DACA recipients have already been taken into custody and at least one has been deported since Trump took office. About 2.3 million people check in regularly with immigration agents; around 2 million of them have no criminal records. Undocumented immigrants with criminal records were ineligible for DACA to begin with.

DHS issued a fact sheet for DACA recipients, which said the information they provide to the government will not be proactively used for immigration enforcement unless there is a risk to national security, public safety or if the person has been summoned to appear before a judge. But they also caution that this policy could change “without notice.”

Meanwhile, many immigration lawyers are advising clients whose permits expire before March 5, the six-month mark, to renew by Oct. 5. Work permits and DACA protections would run for the normal two-year period. Those whose DACA status expires March 6 or later would again fall into unauthorized status.

“In a worst-case scenario, if Congress doesn’t pass anything, March 6 would be a possible start to enforcement actions,” said immigration attorney Lily Axelrod in Memphis. “That would be the beginning of efforts to find and detain people.”

“Now is the time to get politically involved and to lobby members of Congress and the Senate to pass the Dream Act,” said Charles Kuck, an Atlanta-based immigration attorney. “That’s the only way forward.”

Until then, lawyers are continuing to tell DACA recipients not to open their doors to immigration officers unless they have a warrant signed by a judge that they can slip under the door. They are also advising them to obtain any form of official identification available to them today, such as driver’s licenses or municipal ID cards, as well as Social Security numbers, which can be used for housing, banking and educational purposes, even if DACA work permits expire.

“Talk to an immigration attorney now about what to do if you were detained and put in immigration court for removal,” Axelrod said. Some DACA recipients could also qualify for other forms of legal relief, such as marriage- or work-based petitions to stay in the US.

Several government agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security and US Citizenship and Immigration Services, declined to answer questions last week and did not reply to inquiries this morning after Sessions’ statement, pointing PRI instead to the documents they had put online.

The possibility of DACA ending had been on Ramos’s mind frequently in the days leading up to today’s announcement, but he didn’t have much time to think about it as medical school classes began.

“It’s a lot to process. I was sort of just bracing for impact because it seemed that it was going to be rescinded, so I started preparing before it even happened,” he says. “It just brings a lot of emotions that I thought were already suppressed back in the day when we were up and coming with the whole movement of trying to create advancements in this program.”

“I’m sure as we continue forward, the anxiety and the concern for all of this is going to build,” says Ramos. “I’m basically going to have to address it — whether it’s something negative or positive — it’s going to come into my life, and it’s going to be a big part of my life.”

Ramos himself might be in a financial bind after Trump’s decision to end the program. The Icahn School has given him institutional loans, scholarships and grants, but if he loses his work permit, it’s unclear if Ramos will be able to pay back the loans. If no legislative solution to keep DACA in place occurs, he will no longer have work authorization by the time medical school ends — and it’s unclear whether he would be allowed to join a residency program to complete his training.

There are congressional efforts underway to curb the effects of Trump’s elimination of the DACA program. Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham from South Carolina drafted bipartisan legislation that would help keep deportation relief for people like Ramos in place. It would also provide a path to permanent legal status, under certain conditions. Sen. Jeff Flake, a Republican from Arizona, proposed legislation that both provides relief for people brought to the US as children and implements tougher penalties on undocumented people who have committed serious crimes.

House Speaker Paul Ryan said in a statement after Tuesday’s announcement that he wants Congress to act.

“At the heart of this issue are young people who came to this country through no fault of their own, and for many of them, it’s the only country they know. Their status is one of many immigration issues, such as border security and interior enforcement, which Congress has failed to adequately address over the years,” he said.

For now, though, Ramos will keep studying.

“It’s hard to wrap my head around being in New York City and being in a medical school. This goal that I’ve had since I was 12 is now coming in to fruition,” says Ramos. “I had wanted this for so long, so the day was finally here that I was one step closer to actually beginning medical school.”

Almost 2 million people were eligible for DACA and the government had received almost 887,000 applications as of March 2017, according to government data (PDF).

About two-thirds of those who were eligible for DACA applied and three-quarters of these applicants are now in the labor force. One in 4 juggles both work and school, according to a report earlier this month from the Migration Policy Institute.

“DACA really emphasized education,” says Julia Gelatt, senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute. “Because youth with DACA had work authorization and could get better jobs, it was easier to save up, to afford to go to college.”

The program also provided motivation for those eligible to seek higher education in pursuit of better jobs, especially for women. While only 45 percent of the DACA-eligible population are women, 54 percent of those with college degrees are women.

“If you know that when you get out of college, you have that work authorization to get a professional job, that’s an incentive to go to school,” Gelatt says. “It’ll be harder to go to college, and there’ll be less of an incentive to do so if DACA ends.”

Compared to other undocumented workers, DACA recipients are more likely to hold white-collar office jobs with higher pay. One in 5 undocumented workers is in construction, for example. Fifteen percent of the DACA-eligible population work in sales and 12 percent in office and administrative support.

A study jointly by University of California, San Diego, political scientist Tom Wong, the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, and a couple of immigrant advocacy groups, estimates that ending DACA would lead to a $460.3 billion loss in the gross domestic product over the next decade. Texas, which led the effort to repeal DACA, stands to lose $6.3 billion annually, second only to California, which has a $11.6 billion projected annual loss.

“Without that work authorization, the best guess is that young people will have to move into the underground economy and figure out what jobs they can find that pay under the table,” Gelatt says. “It’s less likely that those with higher education will be able to work in the professional jobs that recognize their education and skills.”

Mark Krikorian, director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which seeks to decrease overall immigration to the US, calls DACA “lawless amnesty.”

“Discontinuing this rogue program would not only be the fulfillment of a campaign promise but is the necessary starting point for any negotiation of lawful amnesty for this sympathetic group of illegal aliens,” he wrote in the National Review. He supports legislation for DACA recipients that includes stricter immigration enforcement, such as the expansion of E-Verify for employers to check the immigration status of prospective employees and a reduction in family-based visas.

Laura López, a 29-year-old mother of two US-born children in Provo, Utah, says receiving DACA status has given her the confidence to register her business cleaning homes and offices in her own name. Previously, it was all in her husband’s name.

She’s not surprised by the Trump administration’s announcement, but she is disappointed. Being in immigration limbo is difficult, and this just increases the uncertainty. She’s worried that she will have to return to Mexico, where she hasn’t been since she was 13. The administration’s message this morning did not present DACA recipients honestly, she says.

In his statement, Trump connected the DACA program to violent crime. He said it spurred migration from Central America, including some who joined gangs, but did not offer evidence of this connection. He also generally connected undocumented immigrants to low wages and unemployment for American workers, repeating some of his arguments for a points-based immigration system.

López says it’s unfair to connect DACA recipients to crime.

“We didn't do anything wrong — neither did our parents make a mistake bringing us here. The rhetoric spewed this morning was one of xenophobia and danger brought by undocumented immigrants. That is false in the case of DACA recipients,” she says. “We went through screening, fingerprinting, we were scrutinized and yet Jeff Sessions deemed this ‘insecure’ for the nation.”

López is due to renew her DACA status in January, but she’s not sure whether or not she’s going to go through with the process. She’s not sure about how the Trump administration will use any information she provides. She says she will likely contact her lawyer before she decides.

“I can’t go; I have my kids and my husband,” she says. “I’m afraid of leaving the country. What if I’m not let back in?”

López has tried to change her immigration status before. Her father had applied for US citizenship in 2001, which might have given her a path to legal status without leaving the country to apply. But by then she was married to a US citizen, which complicated matters. To get legal status as the spouse of a citizen, she would have to return to Mexico. And if her application is delayed or denied, she would not be allowed back into the US.

"When we tried to go to other lawyers, here in Provo, I was turned away,” she says. “There was nothing to be done."

Recently, though, she tried again and is working with a lawyer in Salt Lake City who is helping her apply through her father’s status. If that doesn’t work, she will try to get a waiver to gain status through her husband’s citizenship without leaving the country.

The attorney fees are brutal, she says, but she sees it as an investment. They have decided to use their savings to do it. Some legal clinics and pro bono or almost pro bono legal services exist, but otherwise, it’s expensive.

"Not everybody has the means to do it. If it's cheap, they're probably notaries who really don't know,” she cautions. “And that can get people in trouble."

More about Laura López: ‘It's harder than people think, to pack up your bags and leave.’

Trump’s decision to end DACA came after pressure from a group of lawmakers, with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton at the helm. Ten state attorneys general, as well as the governor of Idaho, signed a letter to US Attorney General Jeff Sessions in June saying they would file a legal challenge to DACA if Trump did not end the program by Sept. 5 (PDF). The group previously challenged the Obama-era DAPA program, Deferred Action for Parents of Americans, in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. The court let stand a lower court decision ending the program when justices deadlocked, 4-4. Trump officially ended DAPA when he took office in January.

For Idaho Attorney General Lawrence Wasden, who signed the letter to Sessions, the request was not about immigration, but rather about procedure.

“My signature on this letter is not about targeting immigrant families. Rather, it is consistent with my objection to legislative executive orders as well as encouragement to Congress to fulfill its constitutional responsibility and address these pressing issues,” Wasden said in a statement.

“This announcement from the administration paves the way for our federal lawmakers to finally step up and deal with this very important issue once and for all.”

Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery said in a letter to Tennessee's senators on Friday that he will no longer seek to sue the Trump administration; instead, he'll throw his weight behind the legislation protecting undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children, which was introduced by Graham and Sen. Richard Durbin, an Illinois Democrat.

“Many of the DACA recipients, some of whose records I reviewed, have outstanding accomplishments and laudable ambitions, which if achieved, will be of great benefit and service to our country,” he wrote. “They have an appreciation for the opportunities afforded them by our country.” (PDF)

New York and Washington state attorneys general said on Monday that they would sue the Trump administration if he ends DACA, to protect those who have benefited from the program.

But for Ramos, even as the political machine churns, life must continue. His first day of medical school was on Aug. 14. It included five lectures specifically about anatomy, the spinal column and the embryo.

“You kind of have to find a balance between worrying about it so much and crippling your life and kind of living your life,” says Ramos. “If you let it overwhelm you, then it starts interfering with your life.”

Follow: We're keeping up with Julio Ramos as he navigates his life in the Trump administration.

When Trump made his announcement, Ramos was in the process of working with immigration organizations in the Rio Grande Valley and the Mexican consulate to figure out a way to get his undocumented parents from South Texas to attend Mount Sinai's White Coat Ceremony in New York City in a few weeks. But after conversations with his parents, they decided against the trip.

“My mom has let me know that risk is not worth it, just to be there a couple of days to see me wear that white coat,” says Ramos.

Despite the Trump administration’s decision to end DACA, Ramos plans to continue his advocacy for the program and hopes Congress will take action. He stays hopeful because his medical school has been supportive and he feels the political climate is different now than it was when DACA first began in 2012.

“The nation and a few congressmen know undocumented students fairly well now, and they know we’re here to make the country better for everyone and not just ourselves,” says Ramos. “They know our stories — one of our greatest platforms was sharing our stories so that people become aware of who we are, how we grew up and what we anticipate to do later in the future.”

With additional reporting by Monica Campbell, Lydia Emmanouilidou, Chris Woolf and Joyce Hackel.