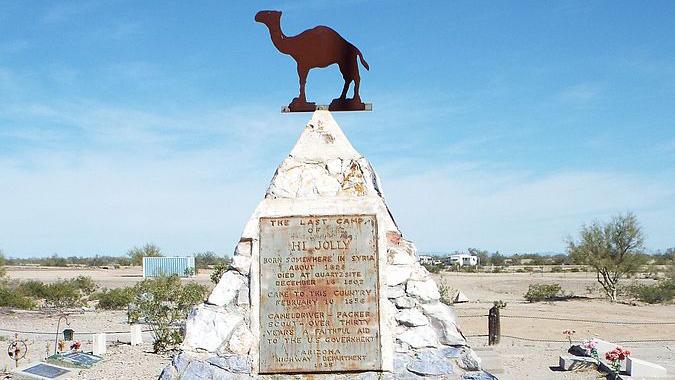

The Hi Jolly Monument in Quartzsite, Arizona, is shown here.

Admitting immigrants and refugees from the Middle East has become a huge flashpoint in US policy with the Trump administration’s efforts to restrict their entry to the US.

So it’s interesting to note that back in the 19th century, one of the first Arab Muslim immigrants to the US — potentially the first-ever Syrian immigrant — came by invitation of the US military.

It was 1848, the end of the Mexican-American War. As part of the spoils, the US government received a huge piece of territory in the West. They wanted to map the land and build roads through it.

“It was going across some dry, dry country where there were very few water holes,” says Marshall Trimble, Arizona’s state historian. “And they needed a beast of burden that could pack a heavy load — you know, 600-800 pounds of baggage — and go a long way without a drink of water.”

So the US government — or at least Jefferson Davis, who was secretary of war at the time — decided camels were the answer. Davis persuaded Congress to approve $30,000 for what unofficially became known as the US Camel Corps. (Davis later became better known as president of the Confederate States during the Civil War.)

But in addition to camels, the Army also needed people who could handle them. So they invited over a few camel drivers from countries where the animals were common. A man named Hadji Ali made a big impression for his particular skill.

Ali was from a port town in Turkey; his mother was Greek, and his father was Syrian. His given name was Philip Tedro, but by the time he was 25, he’d converted to Islam, made a pilgrimage to Mecca and changed his name.

But the name was a problem for his American employers.

“When he gets over here, they can’t say his name,” Trimble says. “It’s hard to roll off the tongue — 'Hadji Ali.' So they start calling him "Hi Jolly." And the name sticks.”

Ali, going by Hi Jolly, set off with the members of the US Army and the imported camels in 1857. Their expedition wound from New Mexico to California. They surveyed the land and created what became a wagon route — and later a big section of the iconic Route 66.

If you look up the Camel Corps today, you’ll find a lot of less-than-fact-based writing saying that camels did not adapt to the American desert, that the whole thing was a failure. But historian Trimble says the truth is that the camels and their mission were highly successful.

Camels, he says, in fact, “gained a reputation … as better than any other animal to carry heavy baggage across the desert.”

The Army lieutenant who led the US military camel mission loved the pack animals, but civilians and cowboys had no interest in riding the strange beasts. Congress ultimately chose not to appropriate more money for camel missions, and in 1861, when the US Civil War broke out, they had other things to worry about.

Also: More American than apple pie, Muslims have been migrating to the US for centuries

The camels were sold at auction, and some of the animals ended up in zoos, circuses and with mining companies. Some escaped into the desert; a few ended up with that Army lieutenant, and some of them ended up with Hadji Ali, who stayed and made his home in Arizona.

Over the years after the Camel Corps, Ali worked as a scout with the US Army. He also prospected for gold, transported goods and even ran a mail service for a while. Occasionally, he would be called on to track down wild camels.

“He was well-respected and well-liked and well-known, too,” Trimble says.

According to a folk song written about Hi Jolly in the 1960s, he liked the area, not to mention the pretty girls. It's a good detail for a song lyric, but Trimble says it's probably not true — after all, there weren’t a lot of women in the frontier lands during Ali's time.

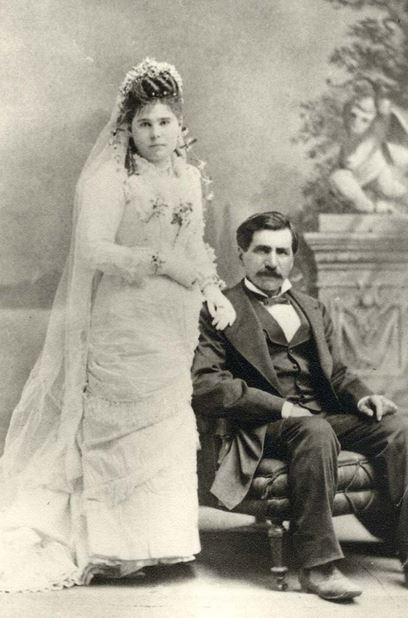

But Ali — who eventually started going by his given name, Philip Tedro — did finally settle down a bit. He married a Sonoran Mexican woman in Tucson and had a couple of daughters, though he spent more time in the desert than with his family.

In 1902, he died in his 70s. There are stories suggesting that he was found dead with his arms wrapped around a wild camel.

According to historian and desert ecologist Gary Nabhan, when Ali died, he was destitute. He had been trying to get a pension from the US Army for his years of service. But despite support from generals, he never received one.

In 1934, the town of Quartzsite, Arizona, built a monument for Ali in their pioneer graveyard. The monument features a pyramid with a camel on top, and the plaque lists it as “the last camp of Hi Jolly.”

The last remaining camel from the original Camel Corps died in a zoo in 1934. The last wild camel was captured in the desert in 1946, though Trimble says with a laugh, “I used to have college students that would tell me they had been in the desert and seen a camel … but I wondered what they might have been smoking.”

Today, there’s a famous ghost story based on a wild camel — and a fair amount of kitsch surrounding what has become the legendary figure of Hi Jolly, an immigrant of Syrian descent and celebrated pioneer of the American West.

More: Idaho’s first Syrian refugee wants Americans to understand their country's vetting process