A ‘man of no land’ tries to find home in Saudi Arabia

Salih Abdullah visited New York City from his home base in Saudi Arabia in the summer of 2017. He looked for a “Muslim utopia” abroad, but was disillusioned with what he found.

When Salih Abdullah, 33, decided to move from the United States to Saudi Arabia, he thought he would have refuge from religious discrimination in a “Muslim utopia” abroad. He never imagined that, five years later, he would find himself so disillusioned with that utopia that he would be considering a move back to the US.

Abdullah met me at a cafe in New York City, while he was taking a vacation from his job in Saudi Arabia as an English teacher for the Saudi National Guard. He says he is just one of many African American Muslims to leave the US because of anti-Muslim bigotry and government surveillance in the wake of 9/11. Like him, he says, many of these expatriates have been sorely disappointed to discover even more unequal treatment abroad, often because of the color of their skin.

Abdullah’s parents converted to Islam when they were teenagers in the 1970s, but he did not identify strongly with the religion as a child. Growing up, Abdullah moved from Hartford, Connecticut, to Columbia, Maryland, and then Atlanta, Georgia. Like many other youths, he dabbled in petty crime and mischief as he struggled to find a sense of place and identity.

“That era ended when I realized I did not have the impoverished background where I needed to have this lifestyle,” says Abdullah, who went on to get his GED and attend college.

Abdullah felt like he still needed to find himself, though.

“I was not getting what I needed in college,” he says. He recalls how, in 2003, while attending Hudson Valley Community College in Troy, New York, “a professor humiliated me in front of the class for not knowing from where I ethnically descend.”

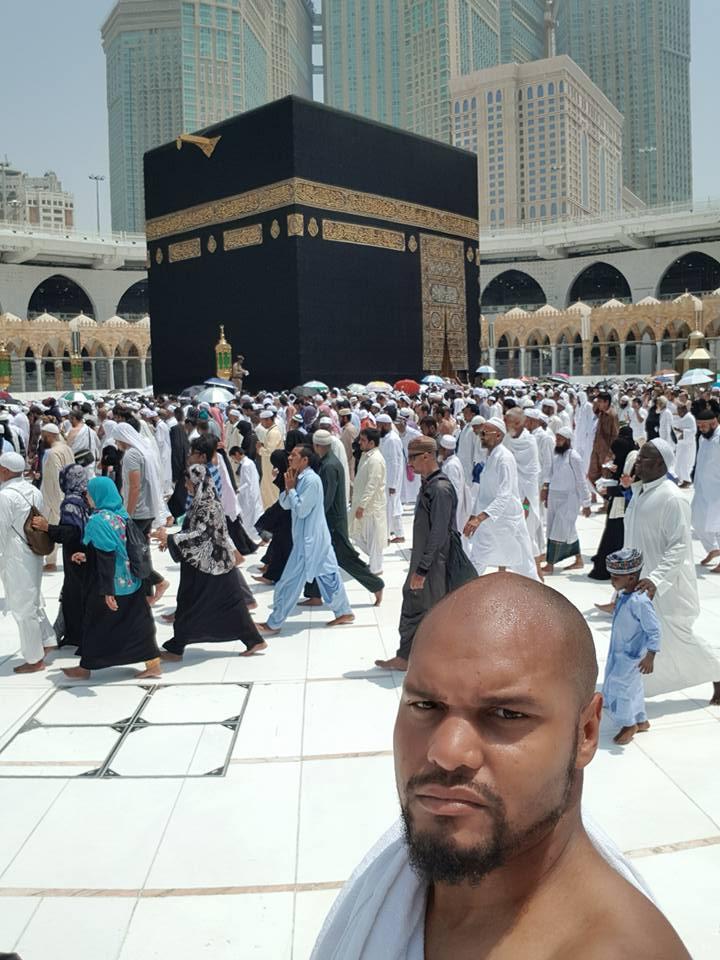

So in 2004, when he was 20 years old, Abdullah decided to embrace his faith and make the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. And instead of returning to the US afterward, he moved to Egypt for several months. It was there, Abdullah says, that his identity as a Muslim began to form and he embraced the Saud-oriented interpretation of Islam called Salafism.

Also: Islamophobia is on the rise in the US. But so is Islam.

Zareena Grewal, a professor of American and religious studies at Yale University, has done ethnographic field research in Egypt, Syria and Jordan, about the influence of transnational Islamic movements on American Muslims. She says that there are communities of African American Muslims studying and forming communities in Muslim-majority countries.

With Islam’s overall emphasis on a global religious community that transcends ethnic and national boundaries, it’s not hard to imagine its appeal to an African American man facing racial and religious discrimination in post-9/11 America. And for the pious, the birthplace of Islam in what is now Saudi Arabia, has an especially powerful draw — especially for Salafis, says Grewal.

Umar Lee, who in 2014 wrote a book about African American converts called “The Rise and Fall of the Salafi Dawah in America,” says that Salafism is more popular among African Americans than it is with white converts like him.

“In Saudi Arabia, you get Muslims from all over the world, so then you get to see how they interact and treat one another,” says Lee. “And there actually is a hierarchy. And the Saudis … are at the top, you know what I'm saying? And then, you know, blacks are near the bottom."

But Grewal cautions that, while racism certainly exists in Saudi Arabia,“ it's not as simple as anti-black racism in the way that Americans understand it.”

“For example, Oprah Winfrey was the top-rated show in Saudi Arabia for many years, among not just women but also men,” says Grewal. “She’s considered very beautiful in a place like Saudi Arabia. It’s not that there’s this rampant anti-black racism across the board in a simple way. There is, in general, a profound xenophobia against anyone who is not Saudi.”

In the years following 9/11, as Abdullah grew wary of the heightened scrutiny of Muslims, he says he did not think twice about the intricacies of Saudi racial dynamics: He wanted to be out of the US and was “naively optimistic” about his prospects abroad.

In 2004, the FBI arrested his imam, Yassin Aref, on suspicion of supporting terrorism. Soon after, Abdullah says, they raided the home of his grandfather for the same reason. Abdullah’s grandfather was not charged with any crime, but Aref was sentenced to 15 years in prison for conspiring to aid a terrorist group and provide support for a weapon of mass destruction. Aref’s supporters maintain he is innocent.

“I know these guys,” says Abdullah. “They're not real threats to the fabric of America, so I'm like, if these guys can get it" — Abdullah pauses before saying the next part — “it's probably likely gonna come on me next.”

“So then right after that they started to basically target everyone else who was close associates of him. So I was in that category,” he says.

“They were right outside my block like every single day," he says. “I fit the profile of a person who could do something. Somebody who's young, between the ages of 20 and 30, educated, has been overseas, and is passionate about Islam. That's the profile."

So in 2012, Abdullah packed up and left the US for a new life in Saudi Arabia. His wife, daughter and newborn son joined him a year and a half later. He used to teach English at Green Tech High in Albany, New York, and, by this point, had earned two master's degrees in adolescent education and educational leadership from the College of Saint Rose. So he took a job teaching English again at Saudi Electronic University in Medina, and by 2014 started working as a private educational consultant on the side.

It did not take long before the dream of utopia began to fade. His clients often didn’t take him seriously. “I have two master’s degrees, I’m almost finished my PhD, but they would look at me and they would say [to themselves], ‘Well, you know you’re black though, so how can you really know what you claim you know?’ And a white guy would come along and he’s barely a bachelor’s degree holder and he has the red carpet laid out for him.”

Abdullah says that the dimension of nationality makes it more complicated than just a question of skin color though. While being black certainly put him at a disadvantage relative to white expats, being American put him in a privileged position compared to those from African or South Asian countries.

"Salaries are often dictated by not just the color of your skin but also what passport you have,” says Grewal.

Abdullah felt increasingly uncomfortable living in a society that treats people so unfairly. Bosses would regularly “forget” to sign the paychecks of their employees. Some employees would have their wages withheld, while the employers who sponsored them held onto their passports.

Domestic workers are notoriously mistreated in the kingdom, to the point that Indonesia even once imposed a moratorium on sending workers there. A common term used to refer to black people in Saudi Arabia, which abolished slavery in 1962, is abeed, meaning “slave.” Abdullah says black people are pointed to and laughed at, even called “monkeys,” while walking in public.

"Not being Saudi means you're inferior. Not being Arab means you're even more inferior. Not being white means you're more inferior,” he said. People with dark skin are “at the bottom of the barrel.”

Some Saudis push back on accusations of societal racism and xenophobia, though. In the major English-language newspaper Saudi Gazette, writer Talal al-Qashqari says that things aren’t nearly as bad as some reports indicate. "It is a fact that despite the presence of thousands of unemployed Saudis in the kingdom, we have not seen any racist behavior or hate crimes in the kingdom like in other parts of the world,” he wrote in a February 2017 article titled “Yes, Saudi Arabia is for Saudis.” “Foreign workers try to form their own mafias in Saudi companies to monopolize jobs preventing others from getting employed. Naturally, Saudis are also prevented from getting a chance to get employed due to this attitude of expat groups.” Mahmoud Ahmad, a managing editor at the Saudi Gazette, has a different point of view though. In a Jan. 2017 article called “Expatophobia,” he wrote that the “language of racism is not our language. It is against Islam and against humanity to paint a negative picture as a whole of others. Expatriates, who worked with us in our country, deserve our thanks and appreciation.”

Still, Abdullah is convinced that the rigidity of the culture makes it impossible for someone like him to get ahead. After five years in Saudi Arabia, Abdullah counts himself among what he says are many foreign Muslims who have “had a rude awakening” in the kingdom.

"The expectation of being just embraced as a Muslim in the Middle East, by other Muslims, and then encountering racism is a real shock to the system,” says Grewal. “Especially when people are going with this presumption that they're trying to leave the US precisely because they're so sick of the racism in the US. So it's really disorienting."

There aren’t statistics about American Muslims who move to Saudi Arabia. We do not know how many go or why. Albert Cahn, legal director at the Council on American-Islamic Relations New York office, says this is not a phenomenon that has been well tracked or studied, but “we definitely hear these stories.”

Abdullah has conducted interviews with other Muslim expats and began writing an academic research paper for his doctoral program in Global and Comparative Education at Walden University, which he has since put on hold. In an attempt to string together a community out of expats with similar experiences scattered across the country, he created a Facebook group, which had 380 members as of August 25th, 2017.

One of Abdullah’s family friends, Labeebah Sabree, is also an African American Muslim expat working in Saudi Arabia. She says she “left America for religious purposes and once I got [to Saudi Arabia], [I] was confronted with racism and behavior that is totally un-Islamic.” Now she is in a bitter dispute with her employer, whom she has accused of withholding her pay.

Jarrett Jamahl Risher is an African American who converted to Islam and also moved to Saudi Arabia for his faith and to escape anti-Muslim discrimination. He’s an English teacher at Saudi Electronic University, where Abdullah used to work. Risher has had a different experience, though.

“Me being a teacher, teaching English and training, my value is very high, so that's the respect they give you. And I give them respect as well,” he told me on the phone from Saudi Arabia. “I would say, it's 100 times less racist than America.”

Neither Abdullah nor his wife and children wanted to return to Saudi Arabia after vacationing in New York. But Abdullah returned in July; he didn’t find a new job in the US and didn’t want to break his employment contract. It’s a situation that was tough on his marriage.

In the long run, though, Abdullah knows there is no place for him and his family in Saudi Arabia. “There's no long-term prospects of you being acclimated into the culture,” says Abdullah. That’s why, the next month, Abdullah abruptly flew back to the US.

“I came back only because it was almost unbearable for me. Hot, dry, boring, lonely."

He took his last exam to be certified as a school administrator in the US and, within a month of his return, was negotiating to become the principal of an Islamic elementary school in Ottawa, Canada, where his wife and children are currently living. That job didn't pan out, so he's returning Saudi Arabia to finish out his contract, and still searching for a position in the US or Canada.

He still sees major problems with American politics and society, but life in Saudi Arabia seems to have given him a new perspective, so he is open to moving back to the US eventually.

“It's the systems of America where you find different types of oppression but in Saudi, it's the whole culture. It's just the way things are in every level, from institutions to the street, to, you know, pay at your job."

But for now, Abdullah is still moving from place to place, just as he did as a child.

“Sometimes I feel like I'm a man of no land,” he says.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this piece stated that Salih Abdullah was hired as a principal in a Canadian school. The position actually fell through before he was hired.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!