What’s the story behind the famous London Fog?

Workers cross Westminster Bridge towards the Houses of Parliament on a misty morning in London, Britain, November 2, 2015.

Cities have unique signatures — and for London, it's fog. A century ago, acrid, corrosive, soot-laden smog killed thousands and shrouded the city in darkness. Yet some Londoners felt affection for the fog, dubbing it “the London Particular.”

London is prone to fog, the actual kind. But in a new book, London Fog: The Biography, author Christine Corton chronicles the man-made kind that would mingle with the natural fog or descend on its own for days at a time — a foul, stagnant, smoky air that would settle over the city, turning day into night and sickening thousands.

Surprisingly, some Londoners were secretly proud of this environmental hazard, and the fog’s murky shadow was reflected by writers, painters and film-makers. Almost all English writers at one time or another used London Fog as a metaphor, Corton says. Dickens, for example, uses the fog as a metaphor for law in "Bleak House" and in "Our Mutual Friend" it becomes a metaphor for the corruption of the city.

English artists, such as George Vicat Cole and W.L. Wyllie, tried to paint the London atmosphere as it appeared to them, “with a kind of dirty black haze, showing steam-powered engines in the distance creating the smog,” Corton says. But these paintings were not acceptable to the industrialists who were buying most of the paintings at that time. “They didn't want to see the products of their own industries being portrayed in paint,” Corton says.

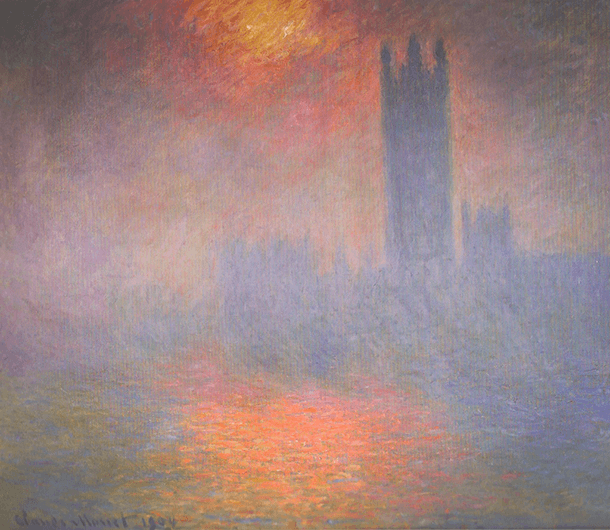

Claude Monet’s famous Impressionist paintings of the Houses of Parliament also captured London’s peculiar colors. “You can see the different colors that the fog produces to his eye,” Corton says. “He's got purples, he's got greens, he's got yellows. You can see that there's an energy behind it that comes across. But, interestingly, he never actually exhibited these paintings in London. Most of them were sold to foreign buyers, so even in the early 20th century this kind of art wasn't really acceptable.”

Corton wrote her book as a biography, because she “wanted to see it in terms of it being born and in terms of it being killed off, dying,” she explains. “I wanted to see it having a kind of personality of its own. It was loved by Londoners, as well as loathed, and that was why it was called all these names. It was named ‘London Particular’ in a very affectionate way because Londoners wanted to show how proud they were of it.”

For Londoners, the fog had a symbolic upside: If there was smoke in the air, it signified employment and industry, and it meant people had open fires to warm themselves, which the local populace loved. The downside, of course, was that it was terribly unhealthy.

“People would quite often cough up black spit, which showed what they were actually taking in," Corton says. "And you could suffocate. If your lungs were weak, if you were elderly or very young, you could actually suffocate because you couldn't get rid of these rather nasty particles from your lungs.”

The fog isn’t just ancient history, either: The 1952 smog, the one that finally, after nearly a century-and-a-half of trying, led to London cleaning up its air, killed between 4,000 and 12,000 people.

“It’s very difficult to give statistics because, of course, the government said, ‘Well, they would have died anyway, because they already had lung issues, they had heart issues, or they died from the flu,’” Corton says. “Quite often, governments would blame deaths on colds or flu. But, nowadays, we reckon the '52 smog probably killed about 12,000 people.”

Just like today, one of the problems with trying to introduce legislation to combat the problem was the vested interests that opposed changing the dirty technology.

“If you're an industrialist and you're trying to make a profit, if you try to improve your chimneys, if you try to clean up the amount of smoke that's going out from the chimney, it's going to cost you money,” Corton says. “It means you have to put in new equipment. It means you have to train your stokers to combust the fire quicker, so this is going to cost you money. So, of course you're going to be reluctant to see an act passed, especially when you yourself as a wealthy industrialist can actually go out and live in the country. You don't have to breathe London's air.”

Sound familiar?

Then, there were other interruptions, like wars and depressions and the like. After World War I, the country was trying to get back on its feet and the last thing the nation wanted to think about was spending money on converting people's coal fires.

After the World War II, a serious effort was launched to produce a really strong Clean Air Act. But by then the coal industry had been nationalized and the Coal Board was supplying a lot of cheap, dirty coal, which was actually producing even more smoke, Corton says.

“We were sending our more expensive coal abroad because we needed the money,” she explains. “So, again, governments are very reluctant to interfere with that. It was really the 1952 smog that made all the difference.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Living on Earth with Steve Curwood

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?