Turning ice into fire: How climate change could mean more volcanic eruptions in Iceland

A butterscotch mountain surges skyward in Iceland.

The first thing you need to know is that Iceland is changing.

Icelander Sveinbjörn Steinþôrsson, a muscular guy in his 40s, grew up hiking on glaciers here. And he says he’s actually seen the changes.

“First trips to the glacier, I was, like, 14, 15 years old,” Steinþôrsson says. “It was easy to find a spot on a glacier to see only white. You could not see the mountain in the north. And you thought you were alone in the world.”

But now, when Steinþôrsson goes to those same places and looks out, he sees mountains and bare land poking through.

“So it has melt[ed] quite a lot, and it is melting fast,” Steinþôrsson says.

And he’s hardly the only one who’s noticed. Freysteinn Sigmundsson, a geophysicist at the University of Iceland, says over his lifespan, he’s seen new landscape open up.

The melting isn’t just affecting Iceland’s surface — it’s also affecting what’s happening underground. And on this geologically active island, it could lead to more volcanic eruptions.

But to explain, we need to go on a road trip in the highlands of Iceland — over a landscape of barren rolling hills of volcanic rock and peaks the colors of dark chocolate and butterscotch.

I hop in a truck that Sigmundsson calls a super jeep. It has modified tires so it can drive across rivers and snow.

We pass between a couple of the biggest glaciers in Iceland — Vatnajökull and Hofsjökull, for those of you keeping track. They sprawl in the distance, on either side of us.

When the jeep stops, we set out by foot up a shallow hillside. After a few minutes, we stop walking.

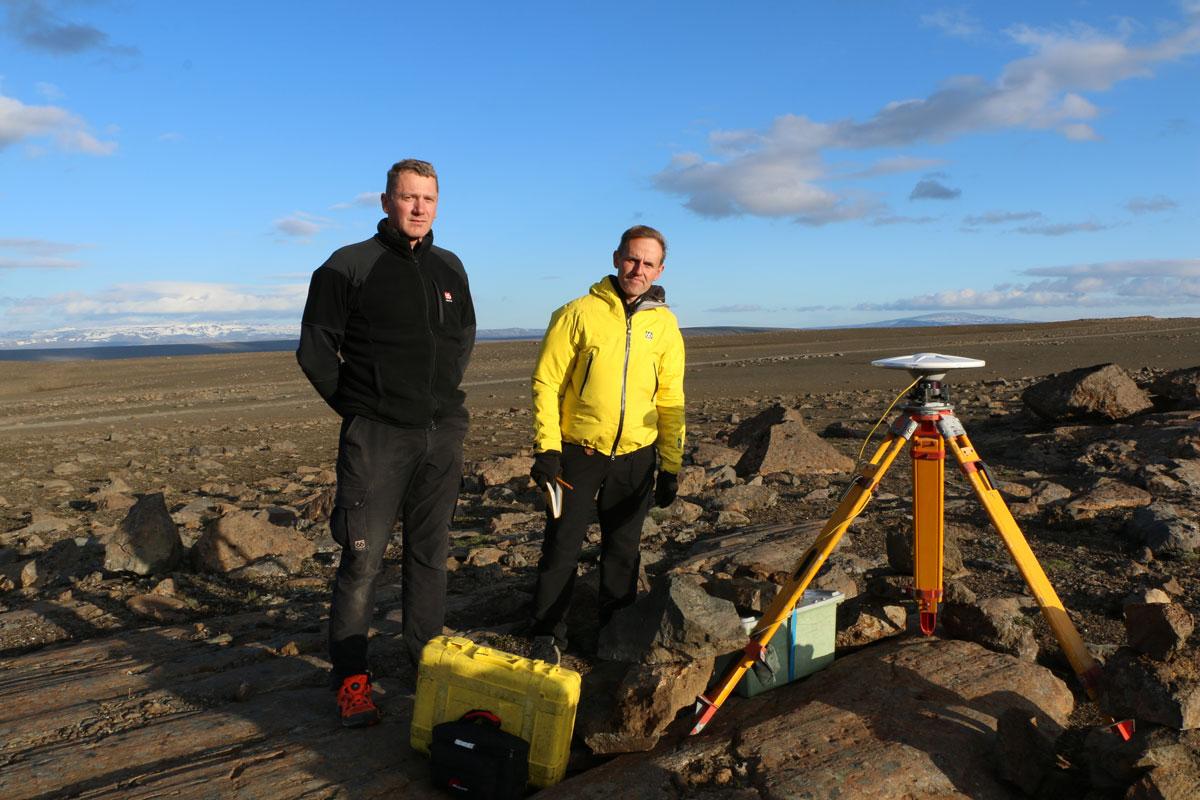

“We have arrived at the site we want to measure,” Sigmundsson says.

It looks like an ordinary slab of brown rock. But mounted to that rock is a metal button the size of a coin.

“So now we just need to get an accuracy of a few millimeters,” Sigmundsson says.

He and his colleague maneuver a big tripod into position over the button below. They secure the whole setup with large rocks, to keep it from being pushed around by the crazy fast winds and heavy rains. On top of the tripod, Sigmundsson perches a special kind of GPS sensor that measures not just latitude and longitude, but vertical position as well. The reason is that the ground here is pushing up.

“Iceland is definitely rising,” Sigmundsson says.

It’s called post-glacial rebound. Think of how heavy all that ice is, pushing down on the Earth. As the warming atmosphere causes the glaciers to melt, that pressure eases and the ground rises up. Sigmundsson’s out here to measure that change.

“The rate of growth is comparable to the growth of your fingernails — about 2-3 centimeters per year if you would not cut them,” Sigmundsson suggests.

In fact, Iceland’s getting higher faster than anywhere else in the world. And the rate is accelerating.

The reason for the quick pace isn’t just the receding glaciers. The land here is also being pushed up by the volcanic hotspot below the Atlantic that originally formed Iceland. In other words, the country’s parked above a churning furnace.

“It’s a melting pot down there,” Sigmunddson says. “I think of it as the fire heart of Iceland.”

For as long as people have been here, glaciers have kept that fire heart reasonably contained. But Sigmundsson’s concerned that the melting ice may trigger a volatile cascade.

“The pressure change induced by the retreating ice caps is enough to generate extra … magma inside the Earth,” he says. “So we can say that global warming is not only causing melting of the ice caps, it is causing melting of the solid earth here under Iceland.”

And here’s what that could mean: More volcanic activity, volcanoes erupting sooner than they would have otherwise, or more powerfully. It could even mean more eruptions of volcanoes still partially covered with ice. That’s bad news.

“If it is a subglacial eruption,” Sigmundsson says, “it melts massive amounts of ice rapidly and generates floods.”

The effects of more volcanoes here could also be felt internationally. Just think back to the eruption here of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 that shut down air space across northern Europe for weeks.

Now, no one has proven yet that this chain reaction from less ice to more volcanic activity actually happens. It’s also possible that disappearing glaciers could mean a delay for some volcanic activity. All of that is what Sigmundsson and his team are here to figure out.

“We can say Iceland is like a laboratory to study this,” he says. “This applies to the whole world, really. If you take the more than 1,000 volcanoes on Earth, many of them are ice covered.”

So what’s learned here will shape our understanding elsewhere. It’s part of a growing field of research into the geological impacts of climate change.

For Sigmundsson’s team, the work starts by collecting data from each GPS station for a couple of days, before moving them to new locations. That’s what he and technician Sveinbjörn Steinþôrsson are doing out here.

The goal is to measure the vertical movement across a broad swath of Iceland — on land that’s undeniably alive.

“[It’s] not just the land sitting there — it [is] a live thing,” Steinþôrsson says. “And it move[s], and it’s breathing.”

And when Iceland exhales, it may just move heaven and Earth.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.