How to save rhinos? By turning their dung into paper.

A one-horned rhino named Baghekhaity stands next to its 10-day-old calf at a zoo in Guwahati, in the northeastern Indian state of Assam.

In a small factory in the northeastern India, a strange type of swill churns in a vat. Bits of chopped-up old hosiery swirl around in almost 200 gallons of water while, at six-second intervals, 72-year-old Mahesh Bora adds fists full of rhino dung.

Yes, you read that right.

Bora is making paper. The rhino dung adds fiber to the paper, and Bora says the whole enterprise will help save the endangered Asian one-horned rhinoceros.

Two thousand of the world’s 2,500 Asian one-horned rhinos live in this northeastern state of Assam, but the rhino population is dwindling rapidly because of poaching and sprawl. Bora says the farmers who live on the edge of the rhino’s forest habitat often see them only as a menace to crops, or a cash opportunity with poachers.

[[{“fid”:”82210″,”view_mode”:”image_on_left”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Manesh Bora says he was inspired to try a new approach to protecting rhinos after others had failed. When he heard about an effort elsewhere in India to use elephant dung in paper, he figured the same could work for rhinos. \”Someone should do it,” he reme”,”title”:”Manesh Bora says he was inspired to try a new approach to protecting rhinos after others had failed. When he heard about an effort elsewhere in India to use elephant dung in paper, he figured the same could work for rhinos. \”Someone should do it,” he reme”,”height”:986,”width”:900,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-left”,”data-delta”:”1″},”fields”:{}}]]“No amount of telling them to save the rhino is actually going to work,” he says. “But nothing works better than economic dependence. If they get some livelihood from rhinos, they’ll always try to save it.”

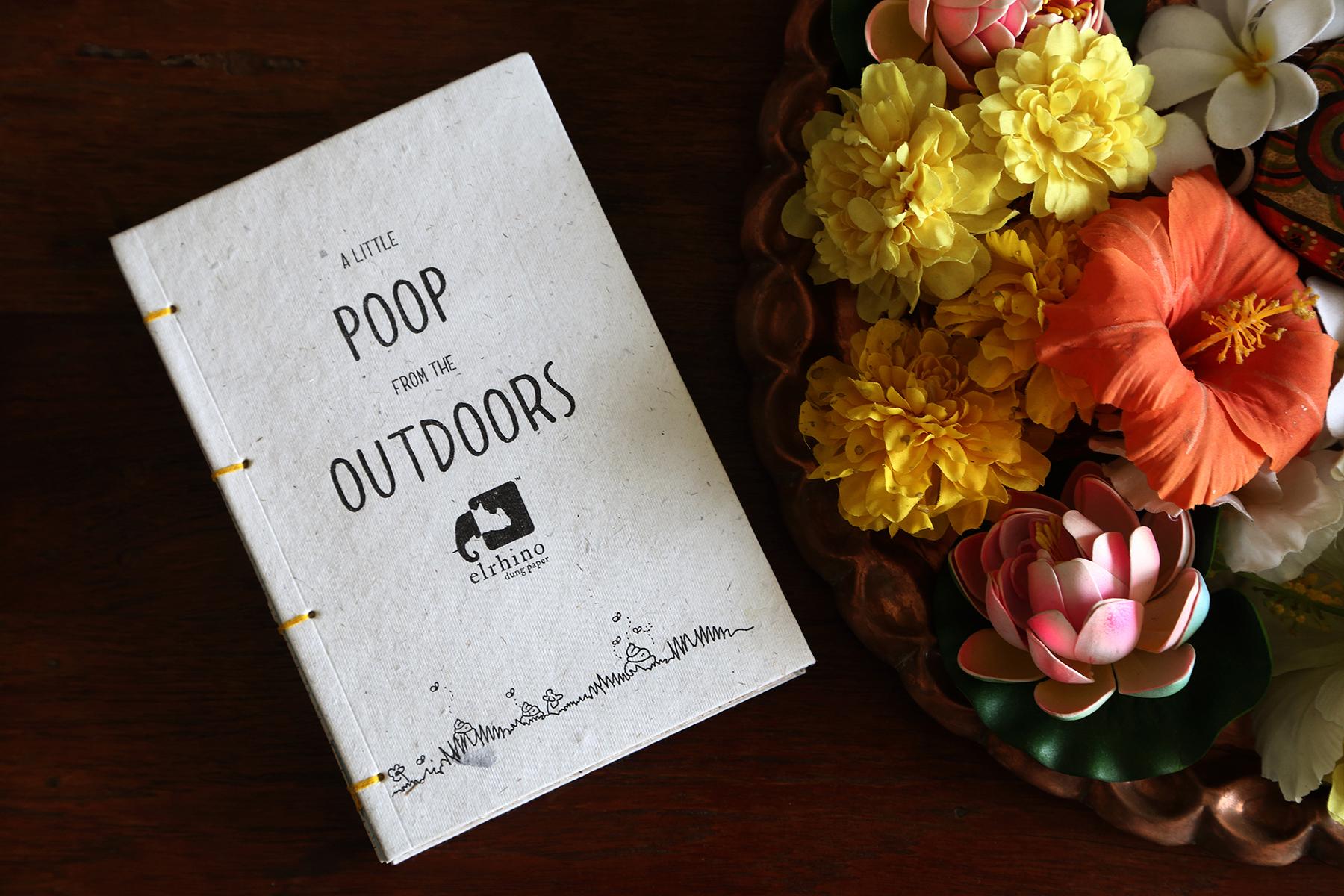

Bora, a retired coal mining engineer, got the idea for the paper factory after reading about a project that used elephant dung. He visited the elephant project, came back to Assam, and set up a business called Elrhino. It started with his wife’s kitchen blender and some window screens, but now employs 50 people. They gather the dung and other natural ingredients and work in the factory.

Bora avoids the national parks, where the dung is protected because it provides fertilizer for the forest. All he needs is the dung on the periphery, where rhinos are often seen plodding across village roads. Even using the relatively smaller amounts on periphery has made a difference in local attitudes toward the rhinos, says Bora’s daughter and business partner, Nisha.

“I can see the acknowledgement of the animal in their livelihood,” she says. “So for us that’s a great validation of what we’re doing.”

Bora says they’re also trying to make a broader impact. Elrhino sells rhino-dung paper, lampshades, diaries and other products as far away as Europe, and each item includes a message about the rhinos.

“Each one of those pieces of communication from me is a little bit of advocacy done,” she says. “[It’s] one person reading about the rhino and feeling concerned about it.”

For now, Elrhino’s business is growing, and Nisha and Mahesh Bora hope to eventually involve entire villages in spinning a stronger thread linking conservation, advocacy and the rhino paper.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)