What’s it like to be a migrant farmworker? One anthropologist lived and worked alongside them.

Anthropologist and doctor Seth Holmes with Triqui children in the mountains of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

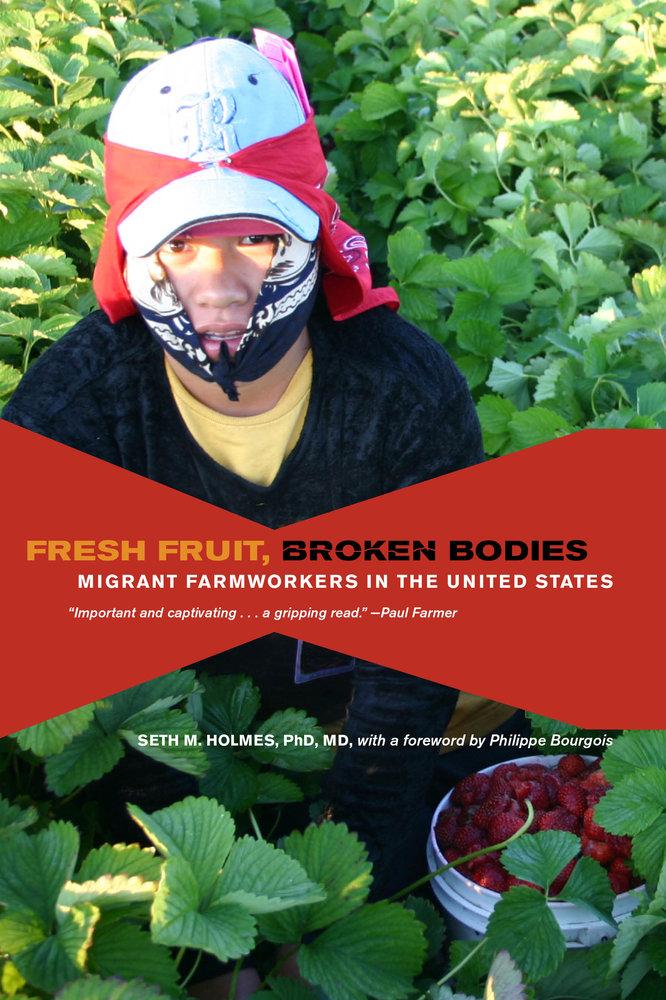

Seth Holmes, a doctor and anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, spent more than a year and half with migrant farmworkers from Mexico — many of them are from the same isolated town in the southern state of Oaxaca — for his book “Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States.”

He met a number of people during his research, from farm owners and doctors to crop inspectors. But he largely focuses on the daily life of the farmworkers — their journeys across the US-Mexico border, away from tough economic conditions back home, and what life is like in the fields along the West Coast of the United States.

Holmes, who lives in San Francisco, spoke with The World’s Monica Campbell about his work.

Q: What led you to this research?

I’d been interested in our food system for a long time and in learning what’s behind the food that we eat. I’d also been interested in the relationship between the United States and Latin America. So this project of living with an extended family of Triqui people from a village in Oaxaca — moving back and forth between their home village and farms up in the US — was a way to look into all of those aspects of our food system: including relationship between the US and Mexico, and the health of people who can be marginalized in our society.

This group of indigenous, native Mexicans was especially compelling to me because they hadn’t been migrating to the US for very long and the process of doing that from their village was taking place at that moment. It wasn’t an old stream of migrants.

Q: Where did your work lead you? You traveled quite a bit.

I worked two summers on the Tanaka Farm up in Washington state, and then I pruned vineyards whenever we could get work in California’s Central Valley in the winter. I also worked alongside parts of the farmworker’s family back in Oaxaca, who were harvesting corn and taking care of the goats and oxen.

Q: How did the owners of the farm in Washington state react to your research proposal, to pick berries on their farm?

At the time, I was a graduate student of anthropology and a medical student, taking about a year and half to do this participation-observation research. I explained to the Tanaka owners that I wanted to pick berries and live in the labor camp and experience it all for myself because that’s how anthropology field work functions. He asked me, “Are you sure you want to pick yourself and do you want to be paid and treated like the other workers, keep up with everyone?” I told him that I did.

I wasn’t good at it, but that was an important part of learning about how the migrant farmworkers experienced some of this. A few times while I was picking, managers or supervisors would walk by me and ask the rhetorical question, “Are you still glad you chose to pick?” But a lot of those same people, when they walked through the fields, if they came and talked to me at all, would also pick some strawberries and put them into my bucket to keep me from falling too far behind. So they were simultaneously making fun of me a bit for doing that work, but also trying to help me keep up.

Q: What was your daily routine like on the farm?

We would start picking really early in the morning, before the sun came up, when it was dark and wet and cold. We would have on all our rain gear, hats and rain jackets. I often didn’t really feel like I was awake yet. I would start picking as fast as I could. I remember that as the sun rose, maybe an hour or two later, I would hit a point where I felt like I can’t do this; I can’t be bent working this fast with my arms without really moving my legs for this long. I remember writing in my journal one day, “This feels like pure torture.”

The Triqui people I lived with picked strawberries seven days a week. I picked one or two days a week, and the rest of the time did interviews and observations on the farm. The nights before I picked, I always felt stressed and kind of sick to my stomach from being aware that it was unlikely that I would be able to pick the minimum weight the next day.

I got better over the course of picking two seasons, but I was never as fast as many of the Mexican farmworkers. I would feel stressed and embarrassed, but I knew I wasn’t going to lose my job, whereas if the other farmworkers missed the minimum weight, they’d have a second chance and then [if they didn’t make the minimum weight once more] they’d be fired for good. I knew on some level that my livelihood didn’t really depend on how many strawberries I picked.

Q: As a doctor, how were you aware of the strain of the work on your body?

I remember every morning feeling like my legs were falling asleep and blood wasn’t able to get where it needed to go. And when I would fill up three buckets of berries and carry them to be weighed — as soon as I stood up to weigh the buckets — the blood would rush back into my legs.

I definitely felt sore at the end of the day, and I had Tylenol and ibuprofen. I also belonged to a local gym. Often, the night after working, I would go to the gym and sit in the hot tub and let some of the soreness go. All the while, I was very aware of this difference between me and the Mexican migrants.

Q: How do you consider the terms “farmworker” and “migrants” and how they are used, including by the media?

There are several different ways that migrant farmworkers are categorized that play into their work and their lives and their bodies not being valued as much. One example is how legal professionals or the media talk about “skilled” and “unskilled” labor. Strawberry pickers are classified as unskilled labor, but my experience picking next to them is that they are very skilled and they are very fast, whereas I was very unskilled in that situation. Our society appears to value certain types of people and certain types of labor more, and it does not appear to value the labor that goes into our food.

Another example of how the terms “migrant”, “migrant worker”, or “immigrant worker” are used unequally is that these are not used to talk about wealthy tech workers here in San Francisco who come from all over the world to work at Google, Twitter, and DropBox. But when we say “migrant worker” we tend to refer to people doing manually labor on farms, and when we say “farmworker” it seems that should mean anyone who works on the farm — the owner, the mechanic, the engineer, the person who went to business school, and the people picking. But “farmworker” always has the connotation of manual laborer and usually people from Latin America doing that work. So the categories of “unskilled labor,” “migrant worker” and “farmworker” all get conflated and this helps reinforce the idea that these people are not as valuable, that their labor is not as valuable, that their health is not as valuable.

Q: What did you hear—among farm owners and workers—about the state of US immigration policy and how it affects agriculture?

When I heard the farm owners talk about farmworkers, they often talked about wanting workers to have permission to be here so that they could count on having enough labor each year, as opposed to worrying that people wouldn’t make it across the border or would get deported.

The farm owners I knew were hopeful that immigration reform would help their labor situation be more predictable.

At the same time, when I interviewed farm owners, they talked about the idea that any ethnic group that starts picking berries or harvesting food after a few generations is no longer going to be doing that. There was this recognition that working on the farms is so bad that no group is going to want to do it indefinitely.

One sad thing that I’ve seen is that some farms have moved to having machines pick their berries, instead of having the work for human labor be more sustainable. It seems sad to realize that the work is hard for humans and then to take it away for all the humans and give it to machines, instead of realizing that it’s hard for humans and try to figure out how to make the situation better.

Q: How has this research affected your own grocery shopping and eating habits?

I’ll never feel the same about berries. Before I worked on farms, I thought that strawberries and blueberries were kind of pure goodness. They are healthy, all natural, especially if you get them organic and local, and it’s only something good. But then I learned that the experience of the people and the bodies that go into providing our grocery stores with these products is really negative and harmful and even violent. Oftentimes, the benefits from those berries go to us, the consumers, and to someone else, whoever owns the business label. But they often don’t go to the individual farmer who owns the farm, and definitely not to the farm worker.

When I go shopping, I look for a few local farms that treat their workers well. If I see those berries, I get excited and I’ll buy them. If I don’t see those berries, then it’s harder to feel 100 percent good about what I’m buying. It’s hard to know where things come from. If a berry label says they’re from Watsonville that could be because the farm is from Watsonville. But it is more likely because the company label is in Watsonville, while the farm itself is in a different state. It’s not a straightforward process buying fruit these days.

I’ll also look periodically at the UFW website to see what’s going on and which farms have contracts and which don’t. There’s also the new Equitable Food Initiative. You can buy produce with the EFI label that you know meets conditions set by certain migrant labor organizations. I do my best to buy produce from farms with UFW contracts, EFI labels or that I have learned from some other source treat their workers well.