China’s American canal could sacrifice Nicaragua’s great lake

Local residents wade into the shallow waters of Lake Nicaragua, the largest in Central America, with the volcanic island of Ometepe in the distance. Many are worried that the lake will be contaminated by the country's new $50 billion Chinese-backed Pacific-Atlantic canal project. The government says the environmental impact will be minimized and outweighed by the project's econmic benefits.

Imagine a Hawaiian island rising up out of a huge lake and you’ve got something like Nicaragua’s Ometepe. It’s the largest island in Central America’s largest lake, Lake Nicaragua. It’s where Luvys and Dayton Guzman grow plantains in the dark soil nutured by the volcano Concepción and water their cows on a black sand beach.

It’s a pretty sleepy place, which is why Luvys Guzman was surprised when a team of surveyors showed up a few months ago.

“They measured everything,” she says, “including our water tanks, laundry, houses and sheds.”

Her husband says the visitors were open about their intentions.

“They told us they wanted the farm for a five-star hotel,” Dayton Guzman says.

Guzman says the surveyors also visited his in-laws next door and other nearby farms. He says he and his wife don’t want to sell at any price. But they may not have a choice.

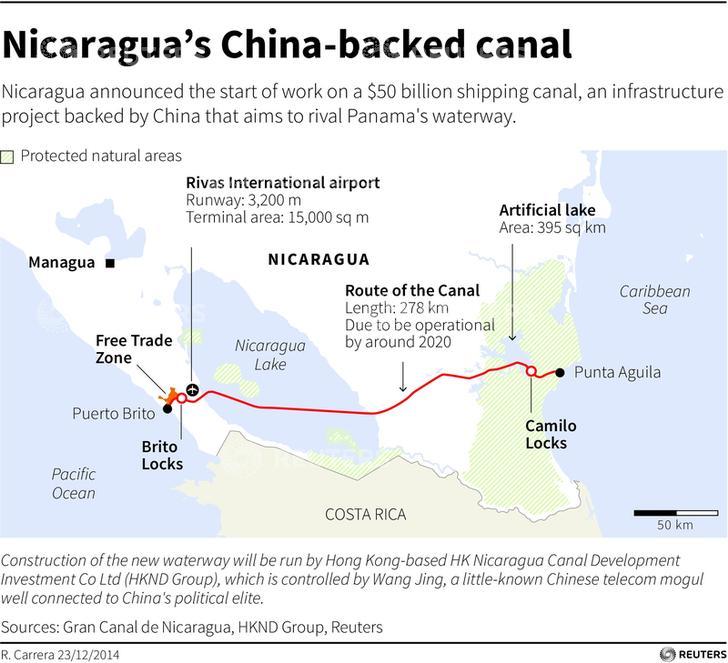

The Nicaraguan government has resurrected a 100-year-old plan to dig a canal across the country from the Pacific to the Atlantic to compete with the Panama Canal. Work began on the Chinese-financed project in December, and the route will go right through Lake Nicaragua.

A 100-year concession the government has granted to a company from Hong Kong allows the firm to take any property it needs for the canal or related projects, including two new ports, a free trade zone and resorts.

Which leaves the Guzmans and their neighbors at a loss.

He and others here are also worried about the project destroying the ecosystems in and around the lake.

The government says building the canal will create tens of thousands of new jobs and be a huge boost to the economy of the second poorest country in the Americas.

And President Daniel Ortega has said he’s not concerned about harming the lake because it’s already contaminated.

Guzman says that’s just not true. “Before the canal project, we never heard the lake was contaminated” he says.

Naturalist Roger Obregón, who works at Ometepe’s Charco Verde Nature Reserve, shares Guzman’s concerns.

“It’s obvious there will be a huge impact on the lake,” Obregón says.

The reserve is home to herons, migratory birds, and ecologically important wetlands. Obregon grew up on Ometepe and says he’s an “aficionado” of nature, but also says he cares about conservation because people here need access to natural resources to survive.

The big question about the canal, he says, is how much the builders will mitigate the damage.

The government has promised to finish an environmental impact study by April. But it’s refused to stop the project in the meantime. The Great Inter-Oceanic Canal, as the project is officially called, is part of Nicaragua’s National Human Development Plan. And project spokesman Telémaco Talavera, president of the Agrarian University of Nicaragua, says the government already knows how the risks and benefits will play out.

“Of course it will have an environmental impact,” Talavera says. “But the overall impact will be highly positive, we’re completely convinced of that. … We need to grow more and create better living conditions.”

[[{“fid”:”81106″,”view_mode”:”image_on_right”,”type”:”media”,”link_text”:null,”field_deltas”:{},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Ometepe Fisherman Santos Lopes says he’s worried about the impact of the canal on the lake but he trusts the government of president Daniel Ortega. \”If the Comandante says we can’t fish but will give us jobs, I’m OK with that,” he says.”,”title”:”Lopes”,”height”:598,”width”:900,”style”:”line-height: 1.538em;”,”class”:”media-element file-image-on-right”,”data-delta”:”4″},”fields”:{}}]]Still, Talavera says the canal builders will take care to protect the lake and avoid the most environmentally sensitive areas.

And some on Ometepe are willing to give the government the benefit of the doubt. In the village of Mérida, Santos Lopes and his son toss fish into a big rubber bucket for sale to their neighbors at 75 cents each.

Lopes is 55, and during the Nicaraguan revolution in the 1980s he says he fought with the leftist Sandinistas, the party now in power and pushing the canal project.

He’s been fishing on Lake Nicaragua for the last 30 years.

“This has been my work,” Lopes says. “It’s supported my family.”

Lopes is worried that the canal will harm fishermen. But he also trusts President Ortega, the former revolutionary leader. “If the Comandante says we can’t fish but gives us jobs,” Lopes says, “I’m okay with that.”

He says he and his family will leave their nets and boats behind and go to work.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?