Three PV-1 planes fly by Kiska Volcano during the Allied invasion of Kiska on August 15, 1943.

It’s one of the least likely pieces of land you can imagine anyone fighting over: an uninhabited, treeless, sub-Arctic island 1,100 miles away from the Alaskan mainland. But according to Canadian military historian Brendan Coyle, the Japanese couldn’t afford to ignore Kiska or its sister island, Attu, during World War II.

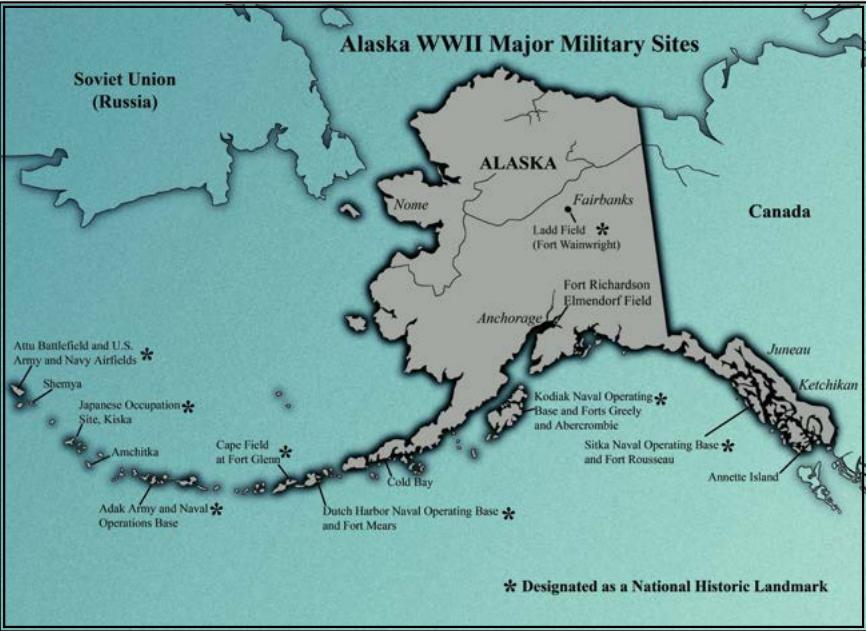

“One of the concerns was that the Americans would 'island hop' all the way to Kiska and Attu and use them as bases from which to hit Japan,” Coyle says.

The Americans were equally concerned about what would happen should Kiska fall into Japanese hands.

The story of the obscure struggle over this remotest of territories is the subject of Coyle’s new book, Kiska. He says the Americans had their work cut out for them defending the island:

“Part of the problem was no infrastructure on the islands," Coyle says. "The Americans had to build everything from scratch, the bases, and that the islands themselves are very inhospitable.”

Exactly how inhospitable? “They get these terrific winds up there that blow to probably over 100 miles an hour,” Coyle says. “It’s perpetually cold and windy and foggy and there’s a good reason why nobody lives there, I guess, because of that.”

Yet the Japanese ultimately sent 7,500 troops to live on Kiska after they seized the island on June 6, 1942. To give you a sense of this number, that was a tenth of Alaska’s entire population at the time.

The Japanese invasion was supposed to be part of a larger effort by the Japanese to take Midway island near Hawaii and destroy the US Pacific Fleet. While the other two efforts were complete failures, the Japanese managed to hang onto Kiska for some 15 months. During their time there, the Japanese built barracks, tunnels and roads. They dug miles of trenches. The Allied troops dropped seven million pounds of bombs on Kiska in an effort to dislodge them.

But the most shocking part of Kiska’s story wasn’t the occupation by the Japanese, but what happened when Allied forces came to take it back.

“What happened was the Americans threw up a blockade around the island, so there were no ships or support for the Japanese getting in and out," Coyle says, but "the Americans withdrew to rearm and refuel their vessels. And in that time, the Japanese were actually able to abandon Kiska within a matter of hours."

Still, this was a good thing, right? The unexpectedly peaceful end to the Japanese occupation?

Not quite: In heavy fog and wind, the American and Canadian troops who moved in to retake the island began shooting at one another, not realizing the Japanese were already gone. This battle without an enemy lasted two days. “What did happen is that some 25 Allied troops did get killed in friendly fire," Coyle says.

Between the fighting and the booby traps and mines the Japanese left behind, more than 300 men ended up dying in the Battle of Kiska.

Today, Kiska is known for a different kind of invasion that's also a result of World War II: rats. And that’s what finally got Brendan to Kiska after years of trying.

“I always wanted to get up there, and it’s impossible to get up there,” Coyle says. “It’s easier to actually get to Antarctica.”

Coyle ultimately crossed paths with a biologist studying the rats’ impact on the native habitat, and Coyle was able to sign on as a field assistant for $20 a day. It gave him a chance to document the ghostly remnants of Japanese shipwrecks and downed fighter planes during the 51 days he spent on the island last summer.

The wind, the cold, the rats, the isolation. I had to ask Brendan: Did he really have to go to Kiska to write this book? I mean, isn’t that what Google Earth is for?

“Yeah,” he says with a laugh, "but there’s nothing like being there.”

Let’s take his word for it.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?