Executive actions can be contentious all over the world

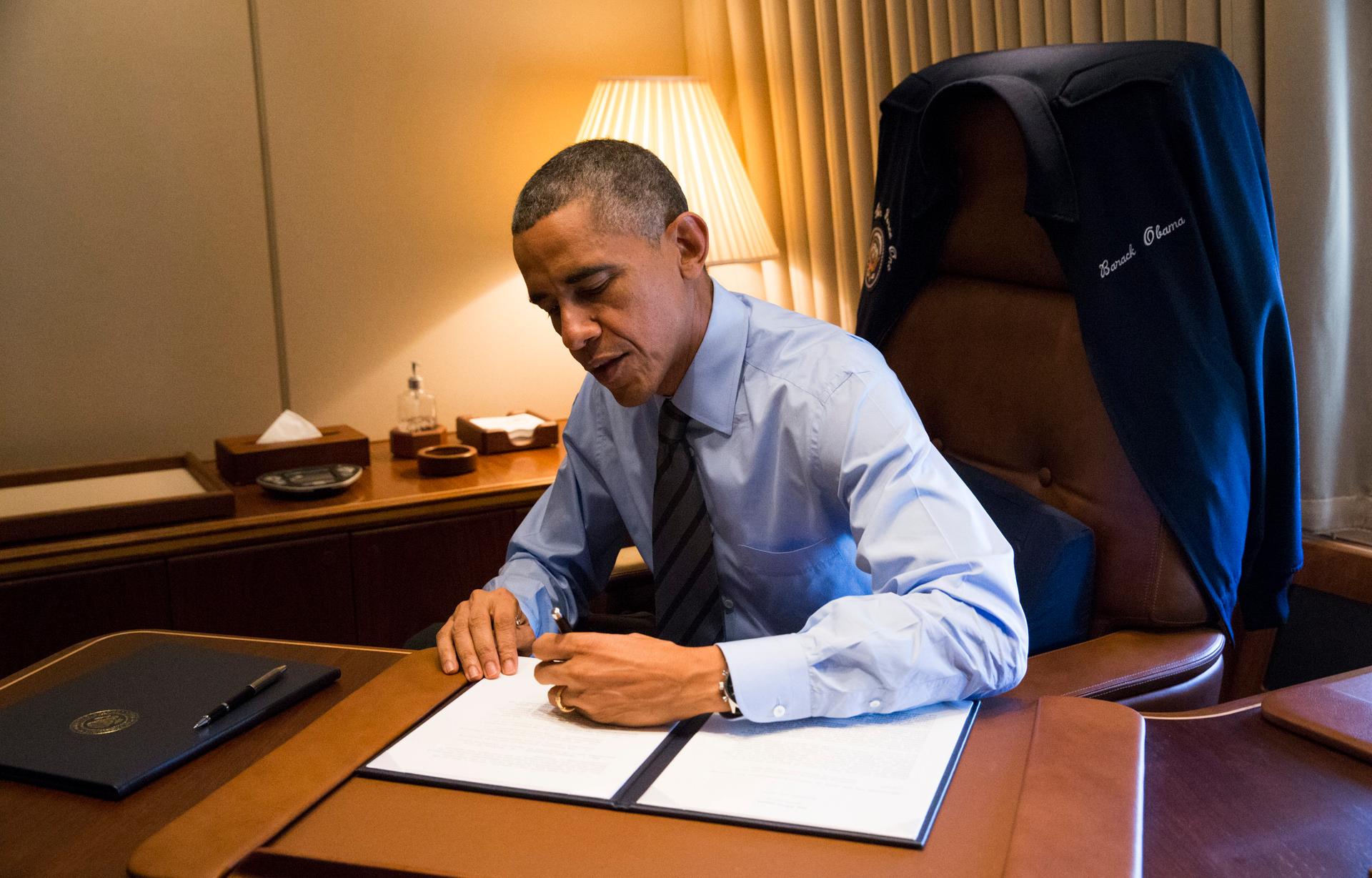

President Barack Obama signs two Presidential Memoranda associated with his Executive Actions on immigration aboard Air Force One on November 21, 2014.

President Barack Obama invoked his executive authority on Thursday to shield as many as five million undocumented immigrants from deportation. Some people are hailing Obama's actions as the biggest changes to immigration policy in decades, but some Republicans on Capitol Hill are calling the moves impeachment-worthy.

House Speaker John Boehner called the president "Emperor Obama" on Thursday, while other conservatives called the executive action undemocratic. That may be by American standards, but how about in other countries?

"If you look around the world at presidential systems — at places where there's a directly elected president that exercises real authority, it's actually more common … for executives to make law by decree in most every democracy than in the US," says John Carey, a professor of government at Dartmouth College.

One recent example in the news comes from Venezuela, where President Nicolas Maduro used his decree power this week to enact as many as 28 new laws. They included a luxury tax, a vice tax and the establishment of new economic development zones.

Carey says the Venezuelan Congress has delegated sweeping authorities to the presidency to make law by decree. As a result, he says, "President Maduro is consistently doing things like re-setting tax rates, in some cases expropriating private firms and making really broad economic policy by decree."

Those decrees come with a major cost, he says: "It reduces transparency enormously, and it allows the Venezuelan legislature to avoid the deliberative process."

A showdown in Indonesia may be a closer parallel to the United States. Joko Widodo, Indonesia's president, recently issued a decree to re-establish direct elections for provincial governors and mayors. The outgoing legislature had abolished them before Widodo took office last month in an effort to undermine his administration.

"The president is taking a unilateral action and effectively daring the legislature to overturn it," Carey says, a situation not too far off from the one in the US over immigration. Obama addressed what he sees as Congress' unwillingness to act, telling lawmakers upset with his executive actions that "I have one answer: pass a bill."

Carey says the view unsurprisingly comes to down to which side of the aisle you're on, no matter what the country: "If I like his policy I call it more democratic. If we agree with the decree it’s a democratic action. If we don't agree with it, it's a usurpation."

Carey suggests taking a longer view. "The struggle between the executive and the legislative branches of government over the boundaries of each other's authority was built in intentionally," he says, "That's going to be a perennial part of American politics. And, by the way, it’s a perennial part of politics in many systems around the world."