The invasive emerald ash borer has killed millions of trees, but researchers hope a wasp can save some of the survivors

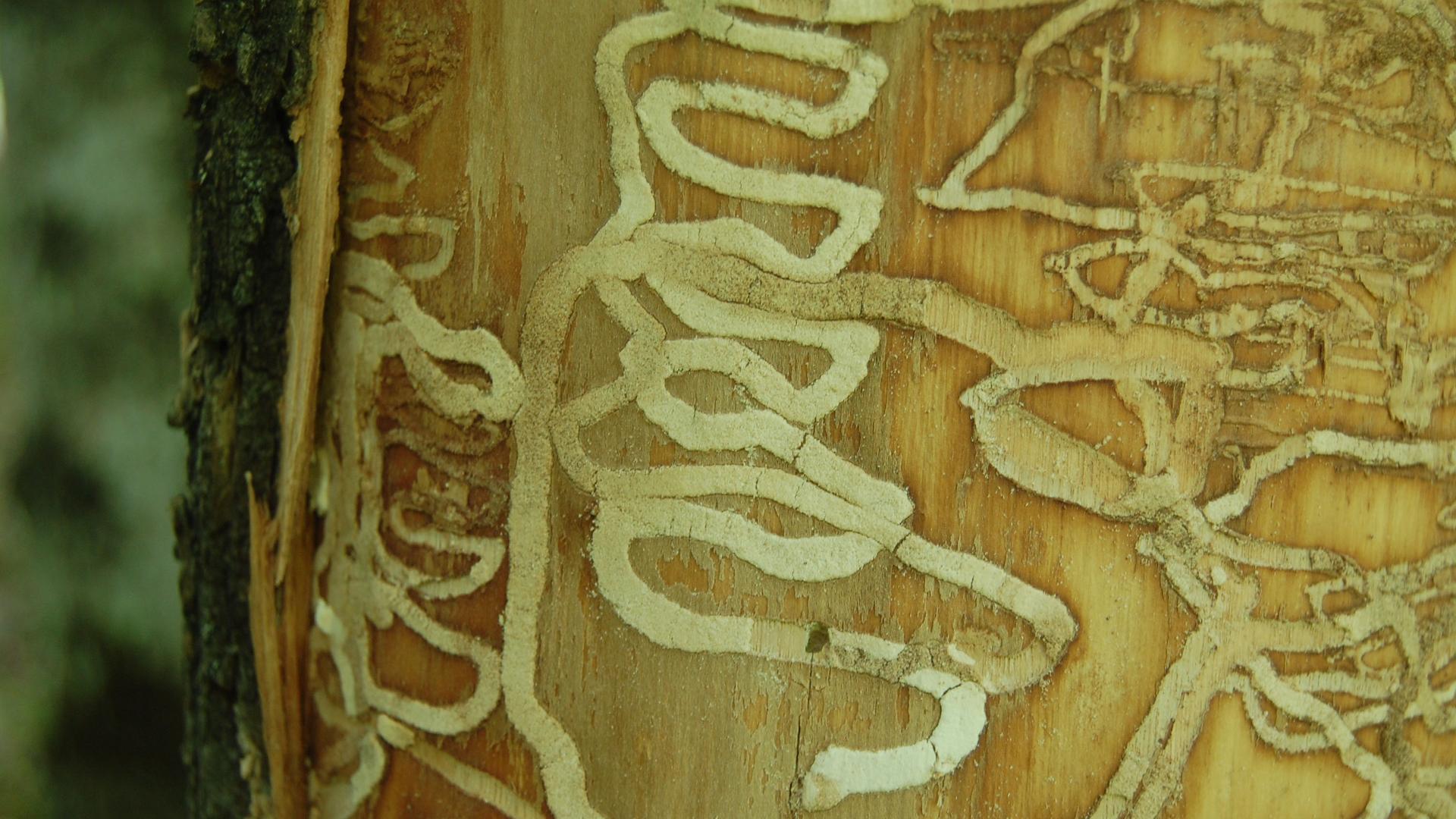

Emerald ash borer tunnels scar an infested ash tree near the Merrimack River in New Hampshire. The invasive insects have killed millions of ash trees in North America over the last decade. Now researchers are releasing a small parasitic wasp in a last ditch effort to save some of those that are left.

A swampy forest in the floodplain of the Merrimack River is one of the first places in New Hampshire where the dreaded emerald ash borer was discovered. These days, Molly Heuss of the New Hampshire Division of Forestry and Lands knows just how to find the tree-munching beetles lurking in green and black ash.

Heuss pokes her draw knife at the bark of a slender ash with waning foliage revealing a bunch of small holes beneath.

“Each of these holes right here,” Heuss says, “when you peel back underneath, you can see the tunneling. The tunneling is actually what kills the tree.”

This ash is still alive, but in recent years, the emerald ash borer has chewed its way through tens of millions of ashes across 24 states and two Canadian provinces, and counting. The beetles were discovered in New Hampshire just last year.

Heuss says the half-inch adults feast on ash leaves and lay their eggs on the bark, then the larvae burrow through the bark and cut off the tree’s nutrients.

But here in New Hampshire, scientists hope to gain the upper hand by introducing a new method for controlling the pests. Heuss points out a blue plastic cup mounted on another ash. Inside the cup there’s a piece of filter paper covered with little emerald ash borer eggs. And each of the eggs is carrying a sort of biological time bomb.

“All of those eggs were infested with oobius,” Heuss says.

Oobius agrili is a parasitic wasp that researchers have just begun releasing here. The hope is that the wasps will do the same thing to the borers that the borers do to the trees — get inside them, and kill them.

The parasites are descendants of wasps brought to the US from China, where the borer is also from. And they are very tiny. “About the size of a pin,” says entomologist Juli Gould, of the US Department of Agriculture in Massachusetts.

“It does its entire development inside a one millimeter long emerald ash borer egg.”

The borers themselves were discovered in North America in 2002. They probably got here by stowing away in shipping crates. Scientists here knew nothing about them at the time, so Gould says they began working with colleagues in China to find a way to control the bugs.

It turned out there were lots of North American ash in southern China. Gould says those trees were infested with emerald ash borers, and the borers were infested with the wasps. So, she says, the Chinese scientists set to work following the lifecycle of both the ash borer and the wasp parasite.

Now, after years of research, the wasps are being deployed in New Hampshire and 17 other states.

Gould hopes they’ll help reduce the borers. But she knows they won’t save every ash.

“We really are not able to rear and release enough insects to save the mature ash trees in a forest,” she says, “because there’s millions of ash borer and we’re releasing thousands of parasitoids.”

But the releases themselves worry some scientists, like Deb McCullough, who studies the ash die-off at Michigan State University.

“I get very concerned about making sure we’re not introducing species that are going to affect non targets,” McCullough says.

There’s a long history of species introduced to fight exotic pests causing bigger problems themselves. So McCullough says more research should be done on using native species to control the ash borer.

But she also realizes the stakes are high and time is short. In some places more than 90 percent of mature ash trees have been killed. And that, she says, “is probably the biggest ecological catastrophe that a lot of the eastern forests have experienced in maybe even hundreds of years.”

But it’s just the latest example of an all-too common scenario.

In his lifetime, New Hampshire forester George Frame has had to adjust to a long line of casualties.

“What’s the world going to be like without ash trees, what’s the world going to be like without elm, and butternut and hemlock,” asks Frame, who works for the Society for Protection of New Hampshire Forests.

“And the list seems to get longer. … It’s something we have to adapt to.”

But Frame hasn’t given up on the ash.

“Nature is so varied,” Frame says. “There are some trees that have a way of repelling or at least resisting these things.”

Frame holds out hope that natural resistance, with the help of the wasps, will give some North American ash trees a fighting chance against the Asian beetles.