After escaping turmoil in Sri Lanka and Nigeria, her next hurdle was surviving LA schools

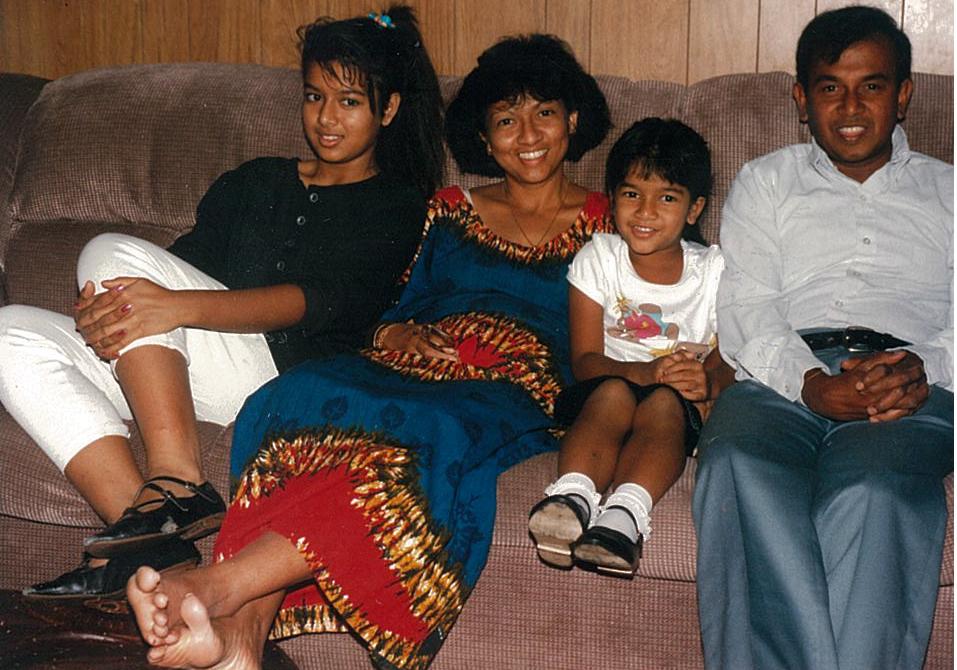

Author Nayomi Munaweera was born in Sri Lanka, and then moved with her family to Birnin Kebi, Nigeria, to avoid civil war. Here Munaweera stands with her mother, Mali, and younger sister, Namal.

Some immigrants can trace a straight line from their native land to the US. Others have a more winding path.

Take Nayomi Munaweera’s journey: She was born in Sri Lanka in 1973, but a brewing civil war convinced her family to move to Nigeria when she was 3. Then, a military coup hit Nigeria in 1984.

“We had to leave quite abruptly,” she says. Next stop: Los Angeles. “It was September, so we were immediately enrolled in school,” Munaweera says. “I think I was in a state of shock for at least three months.”

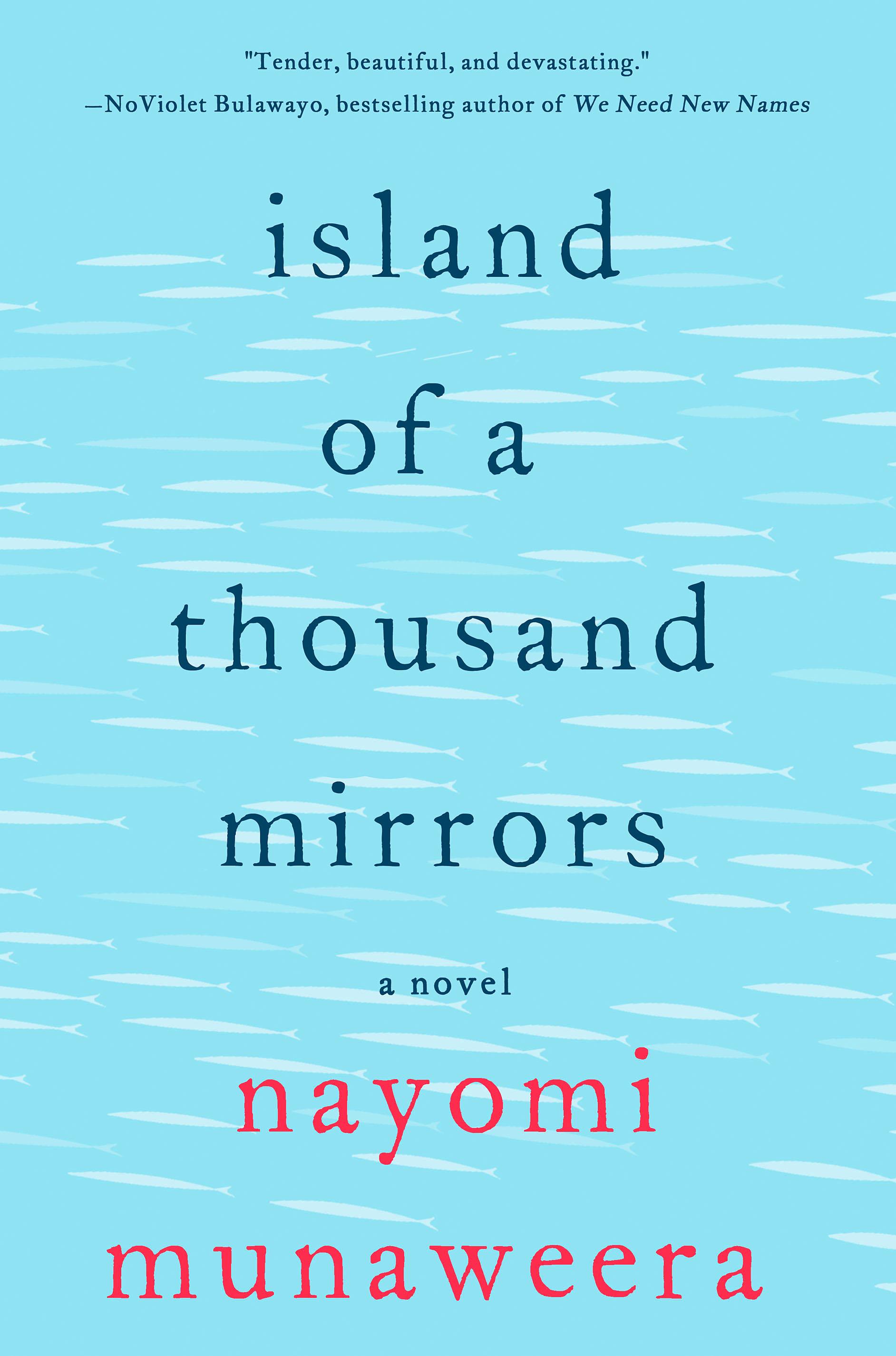

She has definitely found her footing in America. Today, Munaweera is a 41-year-old writer in Oakland. She just published her first novel, “Island of a Thousand Mirrors,” about life during Sri Lanka’s civil war and, in parts, about migrating to the United States.

But when she came to the US at age 12, Munaweera remembers feeling confused about the basics. “I remember being at a party and another Sri Lankan girl saying, ‘So are you from LA?’ And I literally didn’t know that LA meant Los Angeles, so I said, ‘No. Uh, I don’t know?’ I was very confused, and all of the other kids started laughing. But I literally did not understand, really, where I was, or the greater geography of the state or the country."

At school, she also became acutely aware of the rich-poor gap.

Back in Nigeria, she wore a school uniform. But in LA, there was no dress code at her public school. The income divide was clearly displayed and, at the time, Munaweera’s family fell into the low-income category.

“We were quite poor,” she says. “My parents had to start all over again.” During their first few months in LA, her dad worked nights as a parking lot attendant before finishing the series of exams that allowed him to work in the US as a civil engineer — his profession in Sri Lanka and Nigeria.

He eventually moved up the ranks in the LA transportation system. Munaweera’s mom worked as a pre-school aide and now owns several Montessori schools. But during their first days in the US, things were scarce.

“I remember specifically I had two pairs of jeans, a green sweater, a pink sweater, and, I think, two shirts. Those were my choices,” she says. “And these other girls were showing up in school with a new outfit every day.”

Then there was hairspray. “That was new to me!" Munaweera says. "We didn’t have that at the time in Nigeria. We lived in a really rural area there." But the demands were clear: “It was the ‘80s, so you learned about Aquanet."

Also unacceptable: hairy legs. “In neither Nigeria nor Sri Lanka at that time would it have been something to remark upon,” she says. “But in an American high school or junior high school, this was a big deal. You had to shave your legs, you had to shave your armpits. So there was much more attention on the body in a certain way. And these are just lessons you learn and just watch and you learn how to emulate.”

The library was one refuge. “I think the thing that really saved my life in terms of this migration is books,” she says. In rural Nigeria, there was little access to books in English.

“So when I came to America, it was just a feast, the fact that I could go into a library,” Munaweera says. “It was such an incredible feeling of liberation. I mean it was like church! 'Oh my god, I can take any book out that I want?' I think that’s really what was my salvation and has been throughout my life.”

Below, you can read an excerpt from "Island of a Thousand Mirrors" on Scribd.