An oceanographer tells why it will be so tough to find missing Flight 370 in the Indian Ocean

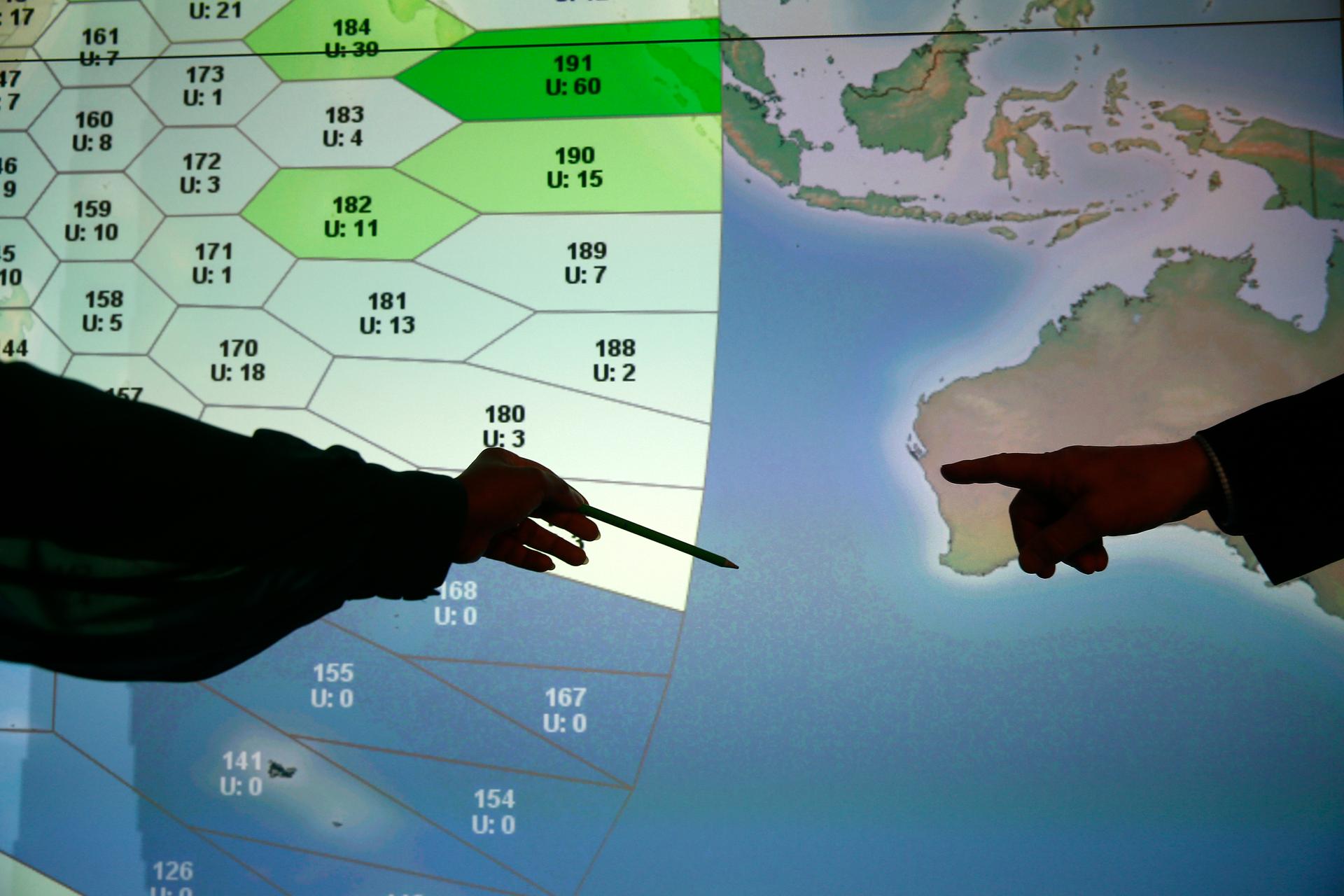

In the days after MH370 disappeared, staff members at the satellite communications company, Inmarsat, in London point to an area in the southern Indian Ocean where they believe the flight ended.

A needle in a haystack is a metaphor that's been used a lot to describe the challenge of finding Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. On Tuesday, Air Marshal Mark Binskin, Australia's deputy defense chief, told reporters at a military base in Perth that they're still trying to determine where the haystack is.

Meanwhile, planes sat idle behind him, grounded because of bad weather over a wide swath of the Indian Ocean about 1500 miles from Perth.

David Gallo, an oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, knows the ocean floor in these waters. He's taken part in expeditions in all the world's oceans and was one of the first scientists to use robots and submarines to explore the deep seafloor.

"It's something called the Southeast Indian Ridge, an underwater volcanic terrain with probably a lot of fresh volcanics at the crest, maybe active vulcanism," he says. Gallo says the water depth at the crest of the underground mountain range is a mile and a half and then goes down to the north and south to about three miles.

Gallo has spent his career underwater. He was part of the team that recovered debris from Air France Flight 447 that disappeared over the Atlantic Ocean in 2009. It took his team two years to find that wreckage. "The terrain is smoother than the Atlantic sea floor where we found the Air France [flight]. But the thing that's really different is that with Air France, we knew we were going to have days when we could have counted on bad weather. With the south Indian Ocean, you're lucky to have days when you can count on decent weather."

Gallo says the weather is always lousy in the area where they're looking for Flight 370, and that has enormous consequences for the expedition to find the wreckage.

"The site is about seven days steam from Perth, and you don't want to be out there for more than a month. So that leaves [between] two and three weeks to be on site," says Gallo. "If the winds are 60 miles per hour and the boat is going up and down thirty or forty feet with the swells and the tides, it's almost impossible to get any work done under those circumstances."

Add to that, he says, the fact that rough seas make it nearly impossible to launch or recover Autonomous Undersea Vehicles or AUVs, which have never been used in that part of the Indian Ocean.

And Gallo is frankly surprised that no debris has been found so far. "In every expedition I've ever been on, we see some bit of debris from the sea. In this case, the satellites have seen objects that the aircraft can't find. The aircraft have seen objects that the ships can't find," he says.

Gallo hopes that more information will lead to a narrower search area. "In the case of the Air France expedition, we spent two months looking in the wrong part of the Atlantic Ocean. So even if you have the right resources, if you're in the wrong haystack, you're not going to find anything."

Gallo says the haystack they're working with now in the search for Flight 370 is about the size of the North Atlantic. "It's immense."

A needle in a haystack is a metaphor that's been used a lot to describe the challenge of finding Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. On Tuesday, Air Marshal Mark Binskin, Australia's deputy defense chief, told reporters at a military base in Perth that they're still trying to determine where the haystack is.

Meanwhile, planes sat idle behind him, grounded because of bad weather over a wide swath of the Indian Ocean about 1500 miles from Perth.

David Gallo, an oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, knows the ocean floor in these waters. He's taken part in expeditions in all the world's oceans and was one of the first scientists to use robots and submarines to explore the deep seafloor.

"It's something called the Southeast Indian Ridge, an underwater volcanic terrain with probably a lot of fresh volcanics at the crest, maybe active vulcanism," he says. Gallo says the water depth at the crest of the underground mountain range is a mile and a half and then goes down to the north and south to about three miles.

Gallo has spent his career underwater. He was part of the team that recovered debris from Air France Flight 447 that disappeared over the Atlantic Ocean in 2009. It took his team two years to find that wreckage. "The terrain is smoother than the Atlantic sea floor where we found the Air France [flight]. But the thing that's really different is that with Air France, we knew we were going to have days when we could have counted on bad weather. With the south Indian Ocean, you're lucky to have days when you can count on decent weather."

Gallo says the weather is always lousy in the area where they're looking for Flight 370, and that has enormous consequences for the expedition to find the wreckage.

"The site is about seven days steam from Perth, and you don't want to be out there for more than a month. So that leaves [between] two and three weeks to be on site," says Gallo. "If the winds are 60 miles per hour and the boat is going up and down thirty or forty feet with the swells and the tides, it's almost impossible to get any work done under those circumstances."

Add to that, he says, the fact that rough seas make it nearly impossible to launch or recover Autonomous Undersea Vehicles or AUVs, which have never been used in that part of the Indian Ocean.

And Gallo is frankly surprised that no debris has been found so far. "In every expedition I've ever been on, we see some bit of debris from the sea. In this case, the satellites have seen objects that the aircraft can't find. The aircraft have seen objects that the ships can't find," he says.

Gallo hopes that more information will lead to a narrower search area. "In the case of the Air France expedition, we spent two months looking in the wrong part of the Atlantic Ocean. So even if you have the right resources, if you're in the wrong haystack, you're not going to find anything."

Gallo says the haystack they're working with now in the search for Flight 370 is about the size of the North Atlantic. "It's immense."