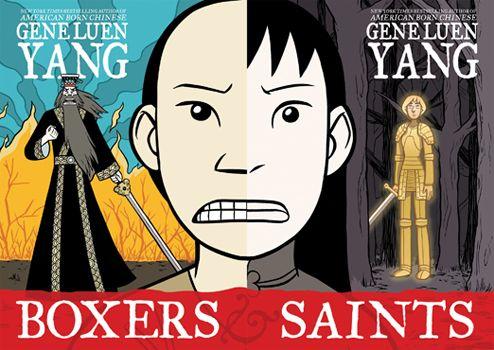

Gene Luen Yang puts China’s Boxer Rebellion in vivid, explosive color in his new graphic novel

In the 21st century, the face of rebellion is often the face of youth. But that's not really a new phenomenon. It was the same way in China at the dawn of the 20th century.

The Boxer Rebellion began in 1898 when Chinese peasants, feeling threatened by the incursion of Western business people and Christian missionaries, formed a secret society called the Yihequan (“Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). The group aimed to purge China of all foreign influence. They became known as “boxers” because they practiced certain boxing and calisthenic rituals they believed made them invulnerable. They killed more than 30,000 Christian converts and Western missionaries before international intervention crushed the rebellion.

Gene Luen Yang’s new graphic noel, Boxers & Saints, follows two fictional Chinese teenagers on opposing sides of the conflict. A boy named Little Bao grows up to become a boxer. On the other side is a young woman named Four-Girl. She's born into a traditional Chinese family that doesn't accept her and converts to Catholicism.

The Boxers, Yang says, were a “ragtag army of poor, illiterate teenagers from the Chinese farmlands who believed that they could call the Chinese gods down from the skies and these Chinese gods would give them superpowers."

In the book, there are dramatic scenes in which the peasants turn into warrior-gods. In these scenes, the illustrations suddenly become large, the colors more intense, the faces terrifying. The book becomes more like a comic book at those moments and less of a graphic novel.

Yang says the dual nature of the book expresses his ambivalence about his own identity as an Asian American Christian.

“Like a lot of Asian American Christians,” he says, “I grew up within this tension between Western belief systems and Eastern culture.”

Just as importantly, Yang is also a huge comic book fan.

“That was one of the ways I found a connection with these Boxers, these teenagers from over 100 years ago,” he says. “These young men first learned about the heroes of Chinese mythology through Chinese opera. China has this long tradition of opera and it's very colorful, it's very dramatic and very stylistic.”

Yang explains that when he read about Chinese opera's place in these young men's lives, he saw a lot of connections between Chinese opera and American superhero comics.

“Both of these media,” he says, “tell stories about heroes who dress in bright colors, who have superpowers, who fight these epic battles for the fate of the world. The way American geeks latch onto superheroes is sort of the way these young men in China latched onto Chinese opera. They felt hopeless and angry and they expressed and dealt with their hopelessness and anger by identifying strongly with these heroes that they watched on stage.”

Yang thinks Asian American kids, and immigrants’ kids in general, may find reflections of themselves in superhero characters who often navigate between two worlds.

“That's something that my Asian American comic book friends and I talk about a lot,” he says. “There are a lot of Asian Americans involved in comic books right now, in every level of the medium. We wonder if, in a lot of ways, we're attracted to this medium because we grew up with these stories of American superheroes. Every American superhero negotiates between multiple identities. Batman isn't just Batman, he's also Bruce Wayne.”

Yang is just as passionate about education as he is about comics. Yang still works as a high school administrator, even with his recent success, his numerous honors and a terrific steady job as the writer of "Avatar: The Last Airbender" comic book series.

Years ago, he was a full-time high school teacher. Yang says it would difficult for him to imagine leaving education completety.

Asked if being a big-time graphic novelist gives him street cred with the high school kids, Yang laughs.

“Not at all,” he says, “It's hard to impress teenagers that you see on a daily basis.”

Hard to impress teenagers — that’s a given in almost any culture.

Boxers and Saints was a finalist for the 2013 National Book Award and was recently nominated for the LA Times Book Prize in the Young Adult Literature category.

This story is based on an interview by PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen, where you'll find other coverage of popular culture, design and the arts.

In the 21st century, the face of rebellion is often the face of youth. But that's not really a new phenomenon. It was the same way in China at the dawn of the 20th century.

The Boxer Rebellion began in 1898 when Chinese peasants, feeling threatened by the incursion of Western business people and Christian missionaries, formed a secret society called the Yihequan (“Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). The group aimed to purge China of all foreign influence. They became known as “boxers” because they practiced certain boxing and calisthenic rituals they believed made them invulnerable. They killed more than 30,000 Christian converts and Western missionaries before international intervention crushed the rebellion.

Gene Luen Yang’s new graphic noel, Boxers & Saints, follows two fictional Chinese teenagers on opposing sides of the conflict. A boy named Little Bao grows up to become a boxer. On the other side is a young woman named Four-Girl. She's born into a traditional Chinese family that doesn't accept her and converts to Catholicism.

The Boxers, Yang says, were a “ragtag army of poor, illiterate teenagers from the Chinese farmlands who believed that they could call the Chinese gods down from the skies and these Chinese gods would give them superpowers."

In the book, there are dramatic scenes in which the peasants turn into warrior-gods. In these scenes, the illustrations suddenly become large, the colors more intense, the faces terrifying. The book becomes more like a comic book at those moments and less of a graphic novel.

Yang says the dual nature of the book expresses his ambivalence about his own identity as an Asian American Christian.

“Like a lot of Asian American Christians,” he says, “I grew up within this tension between Western belief systems and Eastern culture.”

Just as importantly, Yang is also a huge comic book fan.

“That was one of the ways I found a connection with these Boxers, these teenagers from over 100 years ago,” he says. “These young men first learned about the heroes of Chinese mythology through Chinese opera. China has this long tradition of opera and it's very colorful, it's very dramatic and very stylistic.”

Yang explains that when he read about Chinese opera's place in these young men's lives, he saw a lot of connections between Chinese opera and American superhero comics.

“Both of these media,” he says, “tell stories about heroes who dress in bright colors, who have superpowers, who fight these epic battles for the fate of the world. The way American geeks latch onto superheroes is sort of the way these young men in China latched onto Chinese opera. They felt hopeless and angry and they expressed and dealt with their hopelessness and anger by identifying strongly with these heroes that they watched on stage.”

Yang thinks Asian American kids, and immigrants’ kids in general, may find reflections of themselves in superhero characters who often navigate between two worlds.

“That's something that my Asian American comic book friends and I talk about a lot,” he says. “There are a lot of Asian Americans involved in comic books right now, in every level of the medium. We wonder if, in a lot of ways, we're attracted to this medium because we grew up with these stories of American superheroes. Every American superhero negotiates between multiple identities. Batman isn't just Batman, he's also Bruce Wayne.”

Yang is just as passionate about education as he is about comics. Yang still works as a high school administrator, even with his recent success, his numerous honors and a terrific steady job as the writer of "Avatar: The Last Airbender" comic book series.

Years ago, he was a full-time high school teacher. Yang says it would difficult for him to imagine leaving education completety.

Asked if being a big-time graphic novelist gives him street cred with the high school kids, Yang laughs.

“Not at all,” he says, “It's hard to impress teenagers that you see on a daily basis.”

Hard to impress teenagers — that’s a given in almost any culture.

Boxers and Saints was a finalist for the 2013 National Book Award and was recently nominated for the LA Times Book Prize in the Young Adult Literature category.

This story is based on an interview by PRI's Studio 360 with Kurt Andersen, where you'll find other coverage of popular culture, design and the arts.