7 of the most badass women who ever lived (who you’ve probably never heard of)

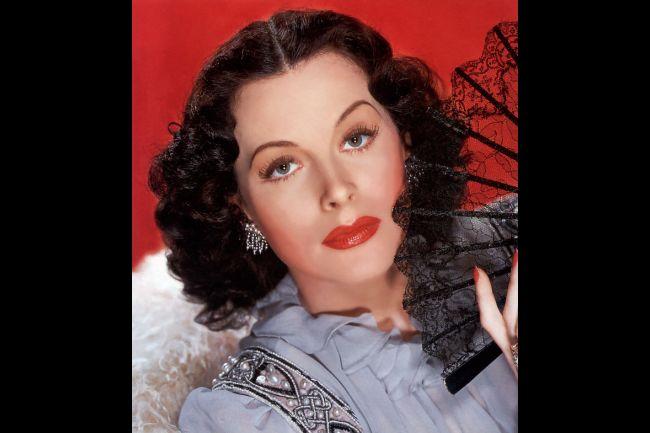

Hedy Lamarr, an Austrian inventor who paved the way for cellphones, WiFi and most of modern life.

For centuries, women all over the world have fought and ruled, written and taught. They’ve done business, explored, revolted and invented. They’ve done everything men have done — and a lot of things they haven’t.

Some of these women we know about. But so many others we don’t. For every Joan of Arc, there’s a Mongolian wrestler princess; for every Mata Hari, there’s a Colombian revolutionary spy; for every Ada Lovelace, there’s a pin-up Austrian telecoms inventor.

More from GlobalPost: 8 reasons Uruguay is not all that

The women who shaped our planet are too many to mention, so here are just a few of the most frankly badass females of all time.

1. Khutulun, Mongolian warrior princess

![]() A modern-day Khutulun takes aim in Ulan Bator. (Koichi Kamoshida/Getty Images)

A modern-day Khutulun takes aim in Ulan Bator. (Koichi Kamoshida/Getty Images)

In the 13th century, when khans ruled Central Asia and you couldn’t go 10 minutes without some Genghis, Kublai or Mongke trying to take over your steppe, women were well-versed in badassery. In a society where skill on a horse and with a bow and arrow was more important than brute strength, Mongol women made just as stout herders and warriors as their men.

One woman, however, had the combination of both skill and might. Her name was Khutulun, and she was not only a devastating cavalrywoman but one of the greatest wrestlers the Mongols had ever seen. Born around 1260 to the ruler of a swathe of what is now western Mongolia and China, she helped her father repel — repeatedly — the invading hordes commanded by the mighty Khublai Khan, who also happened to be her great uncle. Her favorite tactic was to seize an enemy soldier and ride off with him, the explorer Marco Polo recounted, “as deftly as a hawk pounces on a bird.”

Off the battlefield and in the wrestling ring, Khutulun went similarly undefeated. She declared that she wouldn’t marry any man who couldn't beat her in a wrestling match; those who lost would have to give her their prized horses. Suffice it to say, Khutulun had a lot of horses. By the time she was in her 20s and a spinster by Mongol standards, her parents pleaded with her to throw a match with one particularly eligible bachelor. According to Polo, she initially agreed, but once in the ring found herself unable to break the habit of a lifetime and surrender. She overpowered her suitor who, humiliated, fled; she eventually chose a husband from among her father’s men and married him without submitting him to the evidently impossible challenge to out-wrestle her.

More women who fought:

Boudica, the original Braveheart. She led her tribe of British Celts in a bloody, and ultimately doomed, rebellion against their Roman occupiers.

Tomoe Gozen, one of Japan’s few known female warriors, who fought in the 12th century Genpei War. She was described as a peerless swordswoman, horsewoman and archer, with a taste for beheading her enemies.

Mai Bhago, the 18th-century Sikh Joan of Arc. Appalled to see Sikh men desert their Guru in the face of Mughal invaders, she shamed them into returning to battle, defeated the enemy, became the Guru’s bodyguard and later retired to devote herself to meditation.

Maria Bochkareva, a Russian peasant who fought in World War I. She formed the terrifyingly named Women’s Battalion of Death and won several honors, only to be executed by the Bolsheviks in 1920.

Nancy Wake, the New Zealand-born British agent who commanded more than 7,000 resistance fighters during the Nazis’ occupation of France in World War II. She became the Gestapo’s most wanted person, and the Allies’ most decorated servicewoman.

2. Nana Asma’u, Nigerian scholar

![]()

Sokoto Caliphate, the area of northern Nigeria where Nana Asma'u founded her network of women teachers. (AFP/Getty Images)

“Women, a warning. Leave not your homes without good reason. You may go out to get food or to seek education. In Islam, it is a religious duty to seek knowledge,” wrote our second historical lady, Nana Asma’u, who’s proof that the pen is mightier than the sword — and at least as badass.

Born the daughter of a powerful ruler in what is now northern Nigeria, Nana Asma’u (1793-1864) was taught from a young age that god wanted her to learn. And not just her — all women, too. Her father, a Qadiri Sufi who believed that sharing knowledge was every Muslim’s duty, ensured that she studied the classics in Arabic, Latin and Greek. By the time her education was completed, she could recite the entire Koran and was fluent in four languages. She corresponded with scholars and leaders all over the region. She penned poetry about battles, politics and divine truth. And, when her brother inherited the throne, she became his trusted advisor.

She could have settled for being respected for her learning; but instead, she was determined to pass it on. Nana Asma’u trained a network of women teachers, the jaji, who traveled all over the kingdom to educate women who, in turn, would teach others. (The jajis also got to wear what sounds like a kind of amazing balloon-shaped hat, which marked them out as leaders.) Their students were known as the yan-taru, or “those who congregate together, the sisterhood.” Even today, almost two centuries later, the modern-day jajis continue to educate women, men and children in Nana Asma’u’s name.

More women with a cause:

Huda Shaarawi, pioneering Egyptian activist who encouraged women to demonstrate both against British rule and for their own rights. Born in a harem at the end of the 19th century, she shocked 1920s Cairo by tearing off her veil in public. She went on to help found some of the first feminist organizations in the Arab world.

Edith Cavell, English nurse who treated German and British soldiers alike during World War I. Devoted to saving lives, she helped Allied troops escape from occupied Belgium, for which she was charged with treason by the Germans and sentenced to death by firing squad. She died after famously declaring: “Patriotism is not enough.”

Beate Gordon, American who ensured that women’s rights were enshrined in Japan’s constitution when it was rewritten after World War II. She was just 22 at the time, and sick of seeing Japanese women “treated like chattel.”

Lilian Ngoyi, one among many badass South African women who fought long and hard against apartheid. “Let us be brave,” she told fellow female activists, “we have heard of men shaking in their trousers, but whoever heard of a woman shaking in her skirt?” Confined to her house by banning orders, she died in 1980 without ever seeing the democracy she’d given her liberty for.

3. Policarpa Salavarrieta, Colombian revolutionary

![]()

Policarpa Salavarrieta, as painted by Jose Maria Espinosa Prieto.

‘La Pola,’ as she was called during her brief life, was by all accounts daring, sharp-tongued and defiant. She fought to free her land, in what is now Colombia, from Spain’s rule — all while pretending to sit in the corner and sew.

She was born sometime around 1790 and grew up amid rebellion, as resistance to the Spanish Empire strengthened across South America. By the time she moved to Bogota circa 1817, she was determined to play her role. Posing as a humble seamstress and house servant, she would offer her services to Royalist households, where she could gather intelligence and pass it on to the guerrillas; meanwhile, pretending to flirt with soldiers in the Royalist army, she’d urge them to desert and join the rebels. Oh, and she was genuinely sewing the whole time — sewing uniforms for the freedom fighters, that is.

She and her network of helpers (it seems there were several women like her) were eventually discovered. When soldiers came to take her, she kept them engaged in a slanging match while one of her comrades slipped away to burn incriminating letters. She refused to betray the cause and was sentenced to death by firing squad in November 1817. Dragged into the city’s main square to provide an example for anyone with thoughts of rebellion, she harangued the Spanish soldiers so loudly that orders had to be given for the drums to be beaten louder to drown her out. She refused to kneel and had to be shot leaning against a stool, her final words were reportedly a promise that her death would be avenged. Sure enough, she continued to inspire the revolutionary forces long after her execution.

More women who revolted:

Manuela Saenz, a contemporary of Salavarrieta, who became the co-revolutionary and lover of Simon Bolivar. Among other things, she helped him escape assassination; he called her the “liberator of the liberator.”

Vera Figner, a member of the 19th-century Russian middle-class who abandoned her social circle to train as a doctor abroad. She returned at the time of the revolution against the tsar and helped plot his assassination, before being betrayed, arrested, imprisoned and exiled.

The Mirabal sisters, four siblings — Patria, Dede, Minerva and Maria Teresa — from the Dominican Republic who opposed dictator Rafael Trujillo throughout the 1950s. All except Dede were murdered by his henchmen in November 1960.

4. Ching Shih, Chinese pirate

An engraving believed to show Ching Shih.

We don’t know much about where Ching Shih came from. We don’t know where she was born, when, or even her real name. All we know is that once she burst into the public record at the start of the 19th century, she would make it a far more badass place.

She first appears in 1801, when she — then a prostitute aboard one of Canton’s floating brothels — was carried off to marry pirate commander Cheng Yi. Cheng wasn’t accustomed to doing much asking, but his lady love had conditions: she wanted equal share in his plunder and a say in the pirating business. The husband-and-wife team was a success, but lasted just six years before Cheng Yi was killed in a typhoon; at his death, his wife took over his name (Ching Shih means “widow of Cheng”) — and his fleet.

Now at the head of one of Asia’s biggest pirate crews, the Red Flag Fleet, Ching Shih revealed herself to be the brains of the operation. Her strength wasn’t in sailing — so she put the first mate in charge of the ships (having first instituted one of the strictest pirate codes ever seen before or since), and devoted herself to new ways to get rich on land. Extortion, blackmail and protection rackets all proved healthy, if not entirely honorable, sources of income. By 1808, her force had grown so formidable that the Chinese government sent its ships to defeat it; faced with the Red Flag Fleet’s firepower and Ching Shih’s inspired naval strategizing, the armada failed, as did those subsequently sent by the British and Portuguese navies.

Eventually China’s government offered a truce. Just nine years after she’d negotiated a pre-nup with her husband-to-be, Ching Shih managed to extract stunningly favorable terms from the Emperor: in exchange for disbanding her fleet, she won amnesty for all but a handful of her men, the right for the crew to keep their loot, jobs in the armed forces for any pirate who wanted it and the title of “Lady by Imperial Decree” for herself. She retired to Canton to open her own gambling den, married her second-in-command, and died a grandmother at the ripe old age of 69.

More women who did business:

Omu Okwei, a Nigerian businesswoman so successful she was crowned the “merchant queen.” In the late 19th-century, relying primarily on her own intellect, she built up a trade network to buy and sell between Africans and Europeans. By the 1940s it had made her one of the country’s richest women, with 24 houses and one of Nigeria’s first automobiles.

Victoria Woodhull, American stockbroker. Alongside her sister Tennessee, she set up Wall Street’s first female-owned brokerage company in 1870 and made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange. She was also the first woman to run for US president; I don’t need to tell you how that race worked out, for her or any other woman who’s attempted it since.

5. Gertrude Bell, British traveler and writer

![]()

Gertrude Bell on her travels in 1909.

We could characterize Gertrude Bell as the female Laurence of Arabia (“Florence of Arabia,” if you will). But that doesn’t really do her justice. Unlike T. E. Laurence, now better remembered in movies and adventure stories than in real life, well into this century “Miss Bell” remained a well-known figure in the country she helped create: Iraq.

Born in 1868 to a wealthy industrial family in northern England, she excelled in her studies at Oxford. After graduating with the first first-class modern history degree the university had ever awarded to a woman, she traveled the world — twice — became one of the world’s most daring mountaineers, taught herself archeology and mastered French, German, Arabic and Persian. Her intimate familiarity with the Middle East, whose deserts she explored and whose most powerful chiefs she knew personally, made her an invaluable recruit to British intelligence when World War I broke out. After the armistice, she became one of the driving forces of British policy in the Middle East. She mapped out the borders of what would become Mesopotamia and ultimately Iraq, she installed its first king, and she supervised who he appointed to his new government.

Just days before the government was inaugurated and her project was complete, Bell was found dead from an overdose of sleeping pills — whether accidental or intentional isn’t clear. One of her Iraqi colleagues once told her that the people of Baghdad would talk of her for a hundred years, to which she responded: “I think they very likely will.” By accounts, for better or worse, they have.

More women who explored:

Jeanne Baret of France, who in 1775 became the first woman to sail around the world. She did it disguised as a man so that she could assist botanist Philibert de Commerson, who was also her lover. One of them — quite probably Baret — discovered the bougainvillaea plant.

Isabella Bird, a 19th-century Englishwoman who went from sickly spinster to globe-trotting travel writer. She made her way through Asia, North America and the Middle East and was the first woman to be accepted into the Royal Geographical Society. She also famously refused to ride sidesaddle.

Kate Marsden, a British nurse who, in quest of a herb she had heard could cure her patients of leprosy, rode across Siberia on horseback in 1891. The herb didn’t live up to her hopes, but she founded a leprosy charity and wrote several books about her experiences.

6. The ‘Night Witches,’ Russian WW2 fighter pilots

![]()

Members of the 125th Guards Bomber Regiment, one of three all-female Soviet combat squadrons, in 1943 (AFP/Getty Images).

It was their enemies, the Nazis, who gave these women their nickname. Officially, they were the members of the Soviet Air Forces’ 588th Night Bomber Regiment. To the German pilots they fought, however, they were tormentors, harpies with seemingly supernatural powers of night vision and stealth. Shooting down one of their planes would automatically earn any German soldier the Iron Cross.

The legendary 588th was one of three all-female Soviet squadrons formed on Oct. 8, 1941, by order of Josef Stalin. The few hundred women who belonged to them — picked from thousands of volunteers — were the first of any modern military to carry out dedicated combat missions, rather than simply provide support.

The 80-odd Night Witches had arguably the toughest task of all. Flying entirely in the dark, and in plywood planes better suited to dusting crops than withstanding enemy fire, the pilots developed a technique of switching off their engine and gliding toward the target to enable them to drop their bombs in near-silence; they also flew in threes to take turns drawing enemy fire while one pilot released her charges. It was, quite frankly, awesome — as even their enemies had to admit. “We simply couldn’t grasp that the Soviet airmen that caused us the greatest trouble were in fact women,” one top German commander wrote in 1942. “These women feared nothing.”

More women who flew:

Amy Johnson became the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia, among other feats. “Had I been a man, I might have explored the Poles or climbed Mount Everest,” she wrote, “but as it was, my spirit found outlet in the air.” Johnson was killed making a transport flight for her country during World War Two.

Maryse Bastié, a pioneering French pilot who set several of the earliest long-distance records for women. She went on to found her own flying school near Paris.

Bessie Coleman, the first African-American to hold an international pilot’s license. Denied training in the United States, she traveled to France to qualify. She returned home to perform daredevil stunts under the stage name “Queen Bess.”

7. Hedy Lamarr, Austrian inventor

![]()

Hedy Lamarr (Marxchivist/Flickr).

We know, right: total babe. That’s why she had a two-decade career playing femmes fatale in Hollywood movies. But while the rest of her co-stars were sunning themselves, sleeping with each other or picking a substance to abuse, Hedy Lamarr was coming up with the system of wireless communication that would later form the foundation of cellphones, Wi-Fi and most of our modern life.

That’s only one of the many extraordinary things about Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, as she was born to Jewish parents in Vienna in 1914. Aged just 18, she courted scandal by appearing naked in the movie Ecstasy and simulating what may just be the first on-screen female orgasm (she attributed her performance to a humble safety pin, judiciously administered off-camera to her buttocks). Briefly married to a Nazi arms dealer (again: what?), she fled Austria for France and then Britain, where she met Louis B. Mayer and secured a $3,000-a-week contract with his MGM studio.

In between filming and at the height of World War II, she and a composer, George Antheil, came up with the idea of a “Secret Communications System” that would randomly manipulate radio frequencies as they traveled between transmitter and receiver, thus encrypting sensitive signals from any would-be interceptors. Their invention, patented in 1941, laid the groundwork for the spread-spectrum technology used today in Wi-Fi, GPS, Bluetooth and some cellphones. Ever inventive, Lamarr also came up with soluble cubes that would turn water into something like Coca Cola, as well as a “skin-tautening technique based on the principles of the accordion.” Cool.

More women who invented:

Eva Ekeblad, a Swedish noblewoman who in 1746 discovered how to make flour and alcohol from potatoes. Her technique is credited with making thousands of Swedes better fed.

Barbara Cartland, the British author best known for penning many — too many — romance novels, in 1931 helped develop a technique of towing gliders long-distance. It was used to deliver airmail and later transport troops.

Grace Hopper, a US Navy officer who devoted herself to programming after World War Two, led the team that invented the first program to convert normal English into computer commands. We owe her for the terms “bug” and “debug,” apparently coined when she had to pick moths out of an early computer.