Singing the Song of the Nubian Diaspora

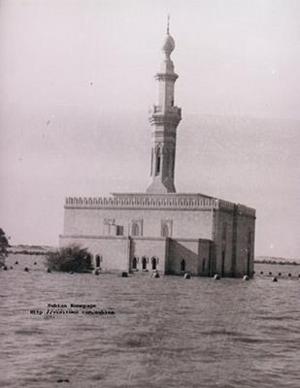

A 1964 image showing a drowned mosque in the Nubian city of Wadi Halfa. (Photo taken from the book “The Nubian Exodus” by Hassan Dafallah)

The area of Northern Sudan and Southern Egypt is the land of the Nubians – an ancient people that go as far back as the 8th century BC Kingdom of Kush. They built a flourishing civilization along the Nile.

With the building of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt came the flooding of the Nubian villages to the north and south, and an exodus of refugees poured into both countries.

Today, many of the sons, daughters and grandchildren of that displaced generation form a diaspora scattered around the world. And some have continued to tell their story through poetry, song and music in a Nubian arts revival of sorts right here in the United States.

The flooding of the Nubian city of Wadi Halfa is a historic event Professor Arif Gamal of UC Berkeley knows intimately. Gamal was a child when his family’s village was about to be submerged. He recalls the day they had to move. “It was a sad, sad day,” he said. “My father left to be with his family, his mother and the villagers. Everything – all their belongings – were wrapped and put into one of the wagons of the train and they all found it in the houses allotted to them.” Reports from that day say that on their way out of town, the people of Wadi Halfa stopped at the town cemetery to bid a final farewell to their deceased family members whose graves would soon be under water.

Gamal has cherished memories of his grandmother’s house, his beloved pet goat, and the pebbly sand between his toes as he ran around his grandmother’s yard barefoot. He says the sadness of that day gave birth to a lyrical and musical genre that emerged from that mass displacement. Nubian “Songs of Return” – poetry and songs reflecting a profound sense of longing for the flooded Nubia – for the Nile, for the land, the palm trees. The songs, Gamal says, were very emotional and romanticized Nubia. Many songs, for example, refer to “fenti,” meaning dates. “All over the Nile you had these date palms,” Gamal says. “You go to the new displaced regions – none of them had a date.” So they sang about them.

Late Nubian music icon Hamza Eldin, a friend of Dr. Gamal, introduced Nubian Songs of Return to the West in the 1970s. The song, “Nubala” sings the praises of flooded Nubian cities like Wadi Halfa and Abu Simbel. His 1982 album “Songs of the Nile” is also a tribute to Nubia.

Those sentiments – and that sound – are being revived, and reinvented today in the United States by a new generation of Nubian-American artists.

Sudanese born musician Alsarah heads a Brooklyn-based band, Alsarah and the Nubatones. She moved to the United States when she was just 12. Alsarah grew up in a family of music lovers, and when she thought to start her own musical career, she didn’t veer toward punk, hip hop, or indie rock like her peers – she sought out her roots and drew on folk songs from Nubia.

Her song “Nuban Uttu”, she says, is a Nubian anthem that calls for unifying the Nubian people after their dispersal.The song isn’t in Arabic, the official language of Sudan. Instead, Alsarah performs it in the ancient Nubian dialect. Singing in her ancestral language is important to her because, as she says, “the dialect and languages are being lost in my generation, the music is really inaccessible to us. There are not enough recordings, or bands that perform it outside the Egypt-Sudan areas.”

Take the I-95 about 190 miles south of where Alsarah is, and you can visit one of the Washington DC area’s many music venues, and see Mosno Elmoseeki, but not without his guitar. He also came from Sudan to the US as a teen, through Egypt, and reflects his Nubian roots through his beats and accompanying instruments like the “tar” drum. He says he had to create his own genre of music – he calls it “Desert Rock”– infusing acoustic alternative rock with Nubian melodies and beats. One example, “Land and Sea”, tells the story, in English, of the character “Desert Boy,” as he debates whether or not to migrate to a foreign land.

Mosno also sees himself as a stereotype breaker, and says he is tired of the constant negative media coverage of Sudan.

Mosno says he wants to help create a new cultural narrative about Sudan through his music “instead of just hearing about the genocides.” In his song “No Kingdom,” written for the soundtrack of the new film “Faisal Goes West,” about a young man from Khartoum migrating to Dallas, Mosno sings tenderly over his guitar and the beat of the tar drum.

“I came here to build a home,

exchanged all my dreams for bricks and stone,

so heavy that it broke my throne,

I’m a king with no kingdom.”

In her rendition of the Ahmed Muneeb song “Bilad Aldahab” or “Land of Gold”, the chorus means “I am human and my address is the land of gold.” For Alsarah, that reflects a sense of lost identity. “How do you identify once you’ve lost your homeland?” she says. “Where does identity now go?”

That sense of a lost identity is shared by NYU student and acclaimed spoken word poetry slammer Safia Elhillo. In her powerful poem, Atlantis, she nearly weeps in grief as she compares the flooding of her ancestors to Hurricane Katrina, and laments what she sees is a neglect of her peoples’ history.

What might be striking to many is how these young Nubian Americans – who have never seen Nubia – are so attached to it and passionate about it. As Alsarah says, “I have felt that longing to go home, to a home you know doesn’t exist. “

But, Nubians like her, Mosno, and Elhillo make sure it exists through their art.