Scientist uncovers species of ocean plants that flee from predators

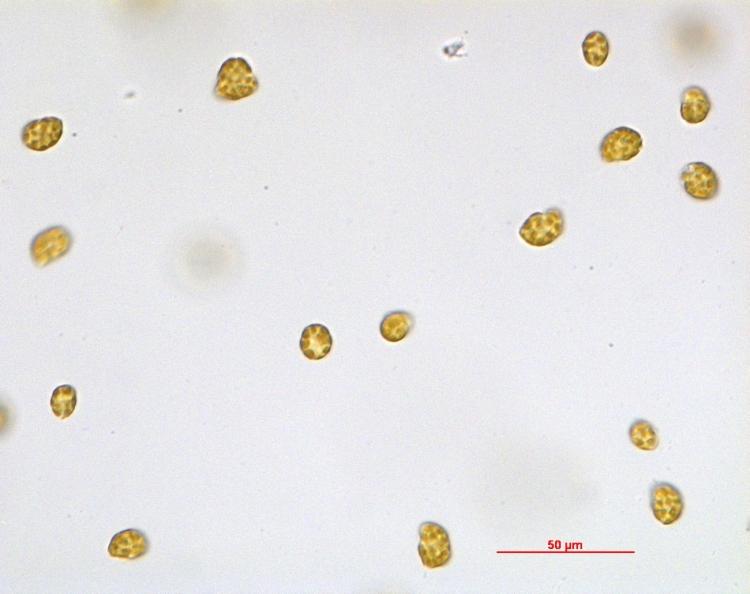

This little plant, Heterosigma akashiwo, is smart enough that when it senses a predator in the area, it flees to an area of safety. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons.)

Plants are capable of incredible things: they supply the earth with oxygen, sequester carbon dioxide and provide us with shade on a hot sunny day.

And now, scientists at the University of Rhode Island have uncovered a surprising new talent in a group of tiny ocean plants — the ability to run away. That remarkable discovery was made by Susanne Menden-Deuer, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island.

This particular plant is not really a plant as we might think of it, but rather a species of phytoplankton that functions much like a plant. It takes the sunlight’s energy and inorganic carbon and produces organic carbon like sugars and the oxygen that we breathe.

“They’re microscopic algae and even though they’re microscopic, they’re so numerous,” Menden-Deuer said, “the power of these numbers and the large area covered results in these microscopic organisms having a tremendous impact on our earth’s ecosystem.

“They generate about half of the oxygen that is breathable in the atmosphere,” she said.

Menden-Deuer’s research focuses on the relationship between predators and their prey. In the course of this research, she was trying to determine if a certain class of predators was able to distinguish between food that was good for it and other food.

“Can it distinguish between, say, a salad and a bag of Doritos, for example,” she said. “These are all single-celled predators. They’re just about the same size as their food, they’re just about as numerous as the phytoplankton.”

So Menden-Deuer set out to map these single-celled predators and the phytoplankton, and how their presence influenced each other.

“By looking at the differences in behavior when they are together and when they are separate, we can tell if things like do they respond to each other,” she said.

They found that not only does the presence of the predator cause the phytoplankton to swim away, but even the mere indication that a predator has been in the area will cause them to relocate. Often, that means going to an area of the ocean that is less salty, an area where the predator can’t survive.

“In our experiment, if the algae could reach an area of low salinity, we call that the low salinity refuge, then indeed the algae could survive,” Menden-Deuer said. “If we force the predator and the prey together in one tank, we don’t allow the algae to swim away anywhere, then the predator will eat all of the prey within about one day.”

Conversely, without the predators in the tank, the algae could roughly double in population every day. And if the algae can flee, they’re still able to roughly double in population — every other day.

“That’s really a key finding of this study is that this fleeing behavior is very effective in increasing the survival of the algae,” she said.

Menden-Deuer said this is the first known example from the plant kingdom of a plant affirmatively fleeing from a predator, versus developing defenses — like thorns — to keep predators at bay.

She added that this discovery gives her hope that, despite the vastness of the ocean, humans stand a chance of unraveling the complexity and understanding how the complex systems work together.

The next step will be looking at other species of phytoplankton to see if this is unique to the heterosigma akashiwo species — or if its more widespread.

“The species we were studying is at times extremely successful in the ocean at making very dense surface slicks that are visible from low-flying aircraft,” she said. “Part of what motivated our study is that we wanted to look at what makes this species so successful.”