On a recent winter afternoon, waiters streamed in and out of the kitchen at the high-end Daryaganj restaurant near Delhi’s airport.

The clinking of silverware and light Hindi music filled the ambiance as Alok Ojha finished his lunch. He had just had one of the restaurant’s most popular offerings: butter chicken.

At any North Indian restaurant in the world, it would be amiss to not find butter chicken on the menu. With a rich tomato gravy laden with cream, succulent chicken and a hint of spices, it is one of India’s best-known curries. “It presses all the buttons that are needed to be pressed for a tasty meal,” food writer Marryam H. Reshii said.

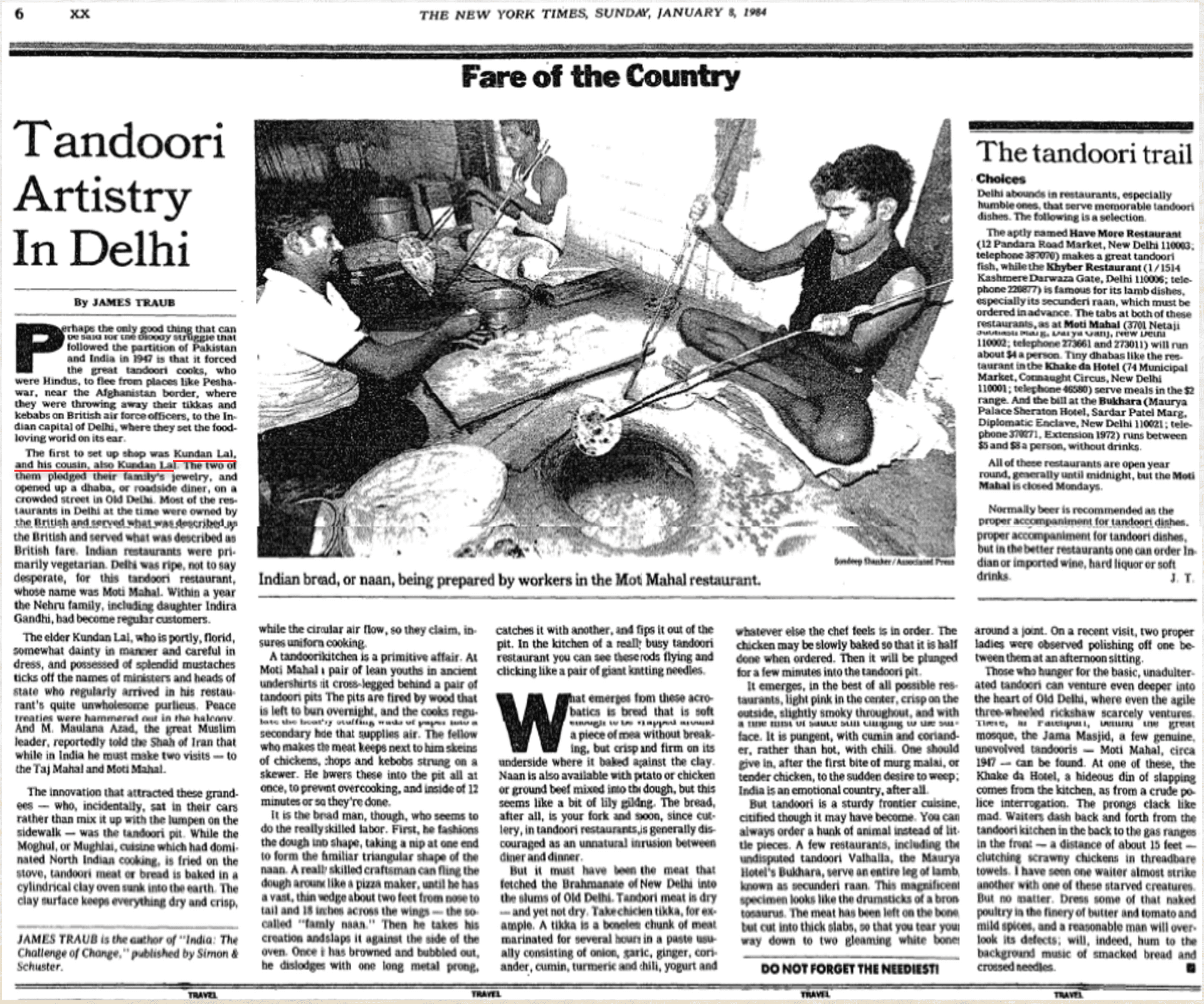

The origins of butter chicken can be traced back to India’s independence — or even before, depending on who you ask. And it’s the subject of an ongoing lawsuit in India, with Daryaganj and another restaurant, called Moti Mahal, battling it out in court. The fight is between the families of two men who came to Delhi from Peshawar in present-day Pakistan after India’s bloody partition in 1947. Both men shared a first name, Kundan Lal, and ran a restaurant together for decades before parting ways amicably.

Daryaganj, whose owners are the defendants in the case, offers something called “the original 1947 butter chicken.” It is a deep orange gravy made of hand-crushed ripe tomatoes, butter and on-the-bone chicken cooked in a traditional tandoor clay oven.

“Typically it tends to be very heavy,” Ojha, the customer, said. “[But] it wasn’t heavy, yet it was very, very tasteful. So, I really enjoyed it.”

Dueling stories

Daryaganj was founded in 2019 by Amit Bagga and his friend Raghav Jaggi as a tribute to Jaggi’s grandfather Kundan Lal Jaggi. The new restaurant is named after a neighborhood in Old Delhi where Kundan Lal Jaggi ran his own restaurant many decades ago. It was there that he invented butter chicken, Bagga says.

It’s a story that Daryaganj proudly prints on its menus. But Monish Gujral doesn’t buy it. He’s the grandson of Jaggi’s former business partner and namesake, Kundan Lal Gujral

“It’s unfair to attempt to, you know, steal [the] legacy of Kundan Lal Gujral,” he said. He insists that butter chicken was invented by his own grandfather and that it predates India’s independence.

In the 1920s, Gujral says his grandfather used to run a restaurant called Moti Mahal in Peshawar where he introduced tandoori chicken — cooking the meat in clay ovens usually used for bread. But “there were challenges to maintaining the succulency of the kebab because they would dry out sitting by the tandoor,” Gujral said, adding that, by the evening, they would become unfit to serve to customers.

To avoid wasting food, Gujral said his grandfather came up with the idea of putting the chicken in a curry. Instead of the commonly-used brown onion gravy which can be quite pungent, he opted for the more subtle tomatoes to let the chicken shine. “The tomatoes don’t overpower the dish,” he said, and have an earthy taste. And that’s how butter chicken came about, he insists.

When India was partitioned, Kundan Lal Gujral came to Delhi and started a new restaurant with fellow refugee Kundan Lal Jaggi and another partner. But at that point, butter chicken had already been invented, Gujral said. “As a partner, you can’t claim a right to an invention that has been done much before.”

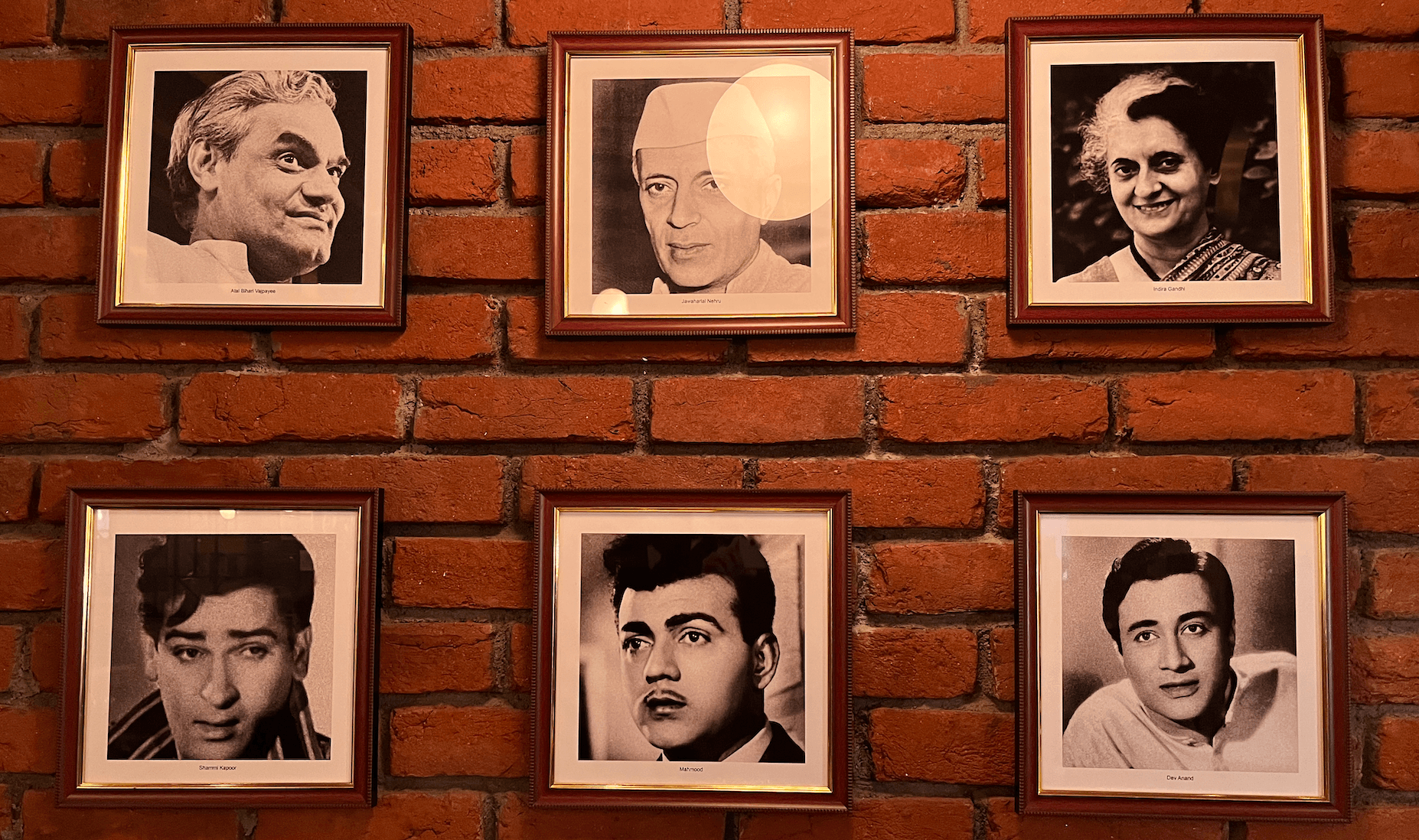

In newly independent India, Moti Mahal, the restaurant of the two Kundan Lals, quickly became one of Delhi’s best. Top politicians and film stars were its patrons. Food writer Marryam H. Reshii went there as a kid and remembers Kundan Lal Gujral, who she said used to walk around with a steel cup in his hand.

“He was the host of the restaurant because he knew everybody and their grandfathers. Most, most charming.”

In 1992, Jaggi left the business. There was no falling out between the two partners, and both have since died. Gujral’s grandson now runs the Moti Mahal brand. “As a custodian of the brand I will fight tooth and nail to protect my family’s legacy,” he said. However, the CEO of Daryaganj argues that the legacy is shared. “Legacy of butter chicken and dal makhani remains with all the partners who started the restaurant together,” Bagga said. “No one can take away legacy from each other.”

Now, it’s up to the Delhi High Court to decide. Moti Mahal is asking for roughly $240,000 in damages for copyright infringement and unfair competition. The CEO of Daryaganj calls the lawsuit “misconceived, baseless and lacking cause of action.”

“Indian food is for sharing.”

But some find this fight over a beloved delicacy distasteful. It goes against the spirit of Indian cooking, Reshii said. “Indian food is for sharing.”

After sampling the butter chicken at Daryaganj, customer Alok Ojha is planning to go to Moti Mahal soon. He and his colleagues are on a quest to find out which butter chicken is better.

“We’ll see what our individual verdict is,” he said.

The court’s verdict is at least a few months away, and the next hearing in the case is scheduled for May.