Xiomara Castro is the first female president of Honduras, a small Central American country about the size of Louisiana. Today, Castro is one of only two women leading countries in Latin America. It is not an easy job in Honduras, a country long considered to be one of the most sexist and violent against women in the region.

Outside of a mall in the capital city of Tegucigalpa, many people blamed Castro for rising inflation.

“It’s great that she’s the first female president,” said Jessica Kuthe, a mall employee. “But in this last year and a half, she hasn’t done much for the people,” she said. “We, poor, can’t even eat beans. The price of everything has gone up too much, and minimum wage hasn’t gone up with it.”

Castro’s government did increase the Honduran minimum wage by 9.8% in February. But clearly, times are hard.

Activists say the bar is that much higher for Castro, simply because she is a woman.

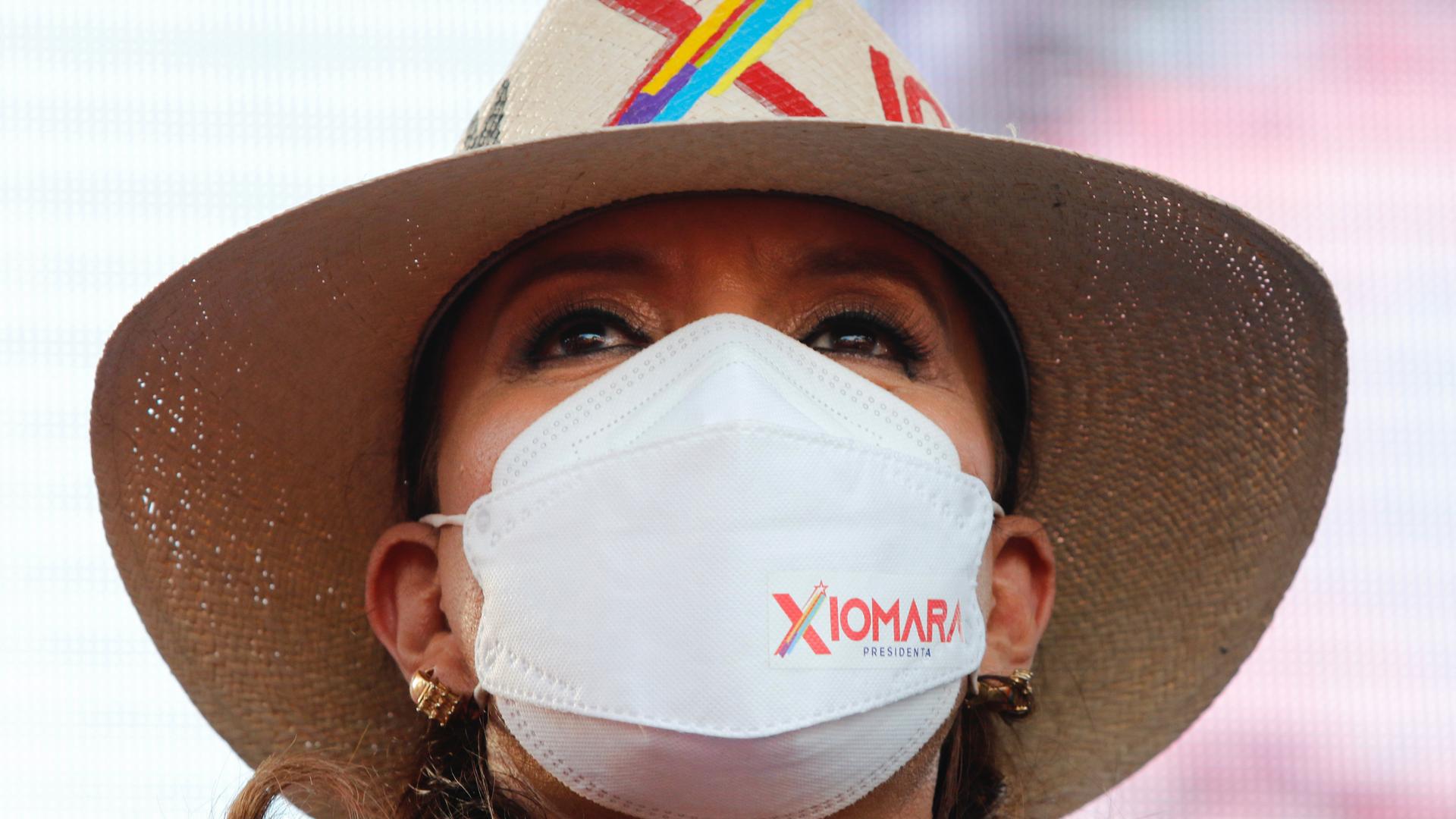

Early last year, Castro was inaugurated in a wave of hope after the Honduran people had experienced years of challenges. Honduras had been rattled by a coup, accusations of rigged elections, human rights violations and violence against women. The previous president, Juan Orlando Hernández, was extradited to the United States after being indicted on drug trafficking and firearms charges.

“Honduran women, I will not fail you,” Castro promised in her first speech. “I am going to defend your rights. You can count on me.”

This was a big promise.

“If we look at the number of femicides, if we look at the number of teenage pregnancies, Honduras has one of the highest rates in the region,” said Alice Shackelford, the UN resident coordinator for Honduras. “There is tremendous violence against women and girls, which is the fruit of a deep-seated patriarchy.”

Two months into her administration, Castro signed an agreement with Shackelford pledging to end violence against women and girls in Honduras.

Castro also approved the use of the emergency contraceptive morning-after pill in March. But the rollout has been slow.

“The president is committed to women’s rights,” Shackelford said, “but there has been pushback. Conservative groups are pushing back. So are anti-women’s rights groups. And they are present in Congress and even in different parts of the government institution itself, which makes it very, very difficult to advance.”

The pushback is also a sign of the divisions within Castro’s own government.

For example, Daniel Sponda, Castro’s own education minister, physically tore up a copy of the government’s new guide for gender inclusion in the classroom on a talk show in late June.

“We are not going to promote values that aren’t part of our society,” he said on air.

Sponda was reprimanded by the country’s human rights minister. But his actions were a sign of the deep divides over women and gender issues in Honduras.

“It’s a symbol of the pact with the church, and with the most conservative ideology in the country,” said Karla Lara, a radio journalist, musician and women’s rights activist based in Honduras.

Protests have hit southern Honduras in recent months against development projects and Castro’s plans for a new progressive tax reform.

In May, opposition congressional officials, who hold a legislative majority, railed against Castro and her party Libre, chanting “Libre never again.”

“They don’t want Castro’s government to succeed,” said Bertha Oliva, a human rights defender and the founder of the country’s Committee of Relatives of the Disappeared. “So, they go against anything she does. They can’t believe that a woman is governing, so they say that ex-president Manuel Zelaya is really pulling the strings.”

According to a recent poll, roughly half the country believes that claim. Castro is the wife of Zelaya, who was ousted in a coup in 2009. According to Oliva, saying he’s really the one making the decisions is offensive to Castro because it insinuates that she isn’t as capable of governing as her husband.

“There is no doubt that much of the attacks and the criticism of Xiomara are clearly a sexist and patriarchal expression,” Shackelford said. “There has been such a huge defamation and misogynistic campaign.”

Analysts agree that female leaders face this same prejudice and discrimination across Latin America. But in Honduras, it’s even more acute, and not just for Castro. Of the nearly 300 Honduran mayors, less than 6% are women.

Lara Bohórquez, of Honduras’ Center for Women’s Rights, said Castro is not perfect. But she’s also fighting an uphill battle.

“We know how hard it is to be a woman in politics. Many women political leaders suffer political, gender violence,” Bohórquez said. “There’s physical, verbal and sexual violence — all part of a strategy to stop women from participating in these spaces.”