Any economic crisis will impact poor and working-class people first and with the strongest repercussions. But in Sri Lanka, where inflation hit 61% last month, people across the economic spectrum are being squeezed. Essentials such as gas and medicine have become hard to find, even for thosewho have the means.

As recently as 2016, the World Bank called Sri Lanka a “development success story.” After the country’s civil war ended in 2009, the gross domestic product in the middle-income nation was rising, and poverty was on the decline.

“There was a lot of reason to be optimistic,” said economist Anushka Wijesinha, co-founder of the public policy think tank Centre for a Smart Future.

He pointed to decades of investment in social infrastructure, health and education, and a tourism industry that was taking off. Foreign and domestic investments had started to flow and jobs were being created in the apparel industry and other sectors.

But that postwar optimism was relatively short-lived, and has all but evaporated today. The country’s economic crisis has sent the quality of life plummeting in the Indian Ocean island nation of 22 million people.

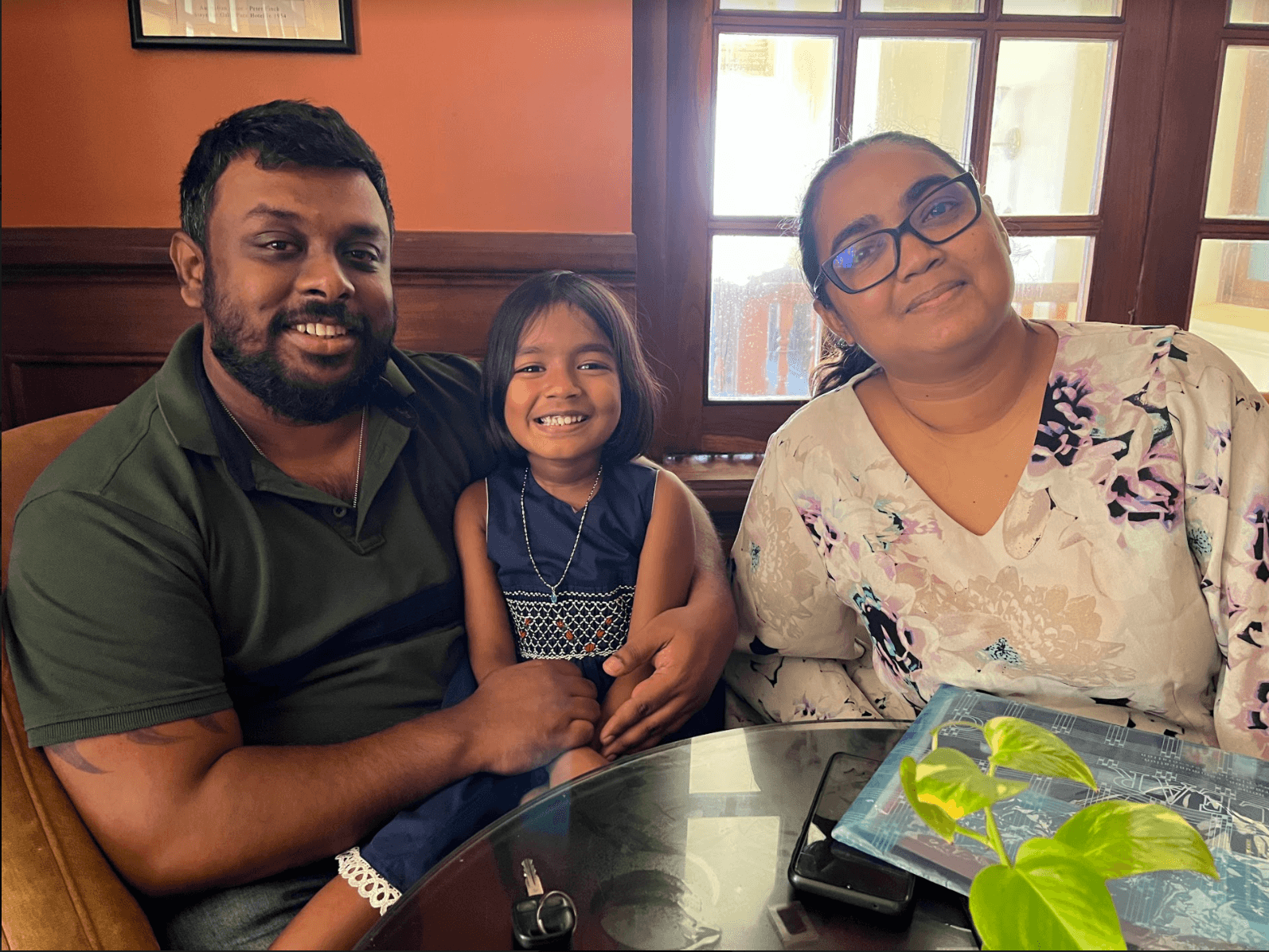

Piumi Mark and Alexander Mark, for example, who both work in online marketing outside of Colombo, found themselves unable to get to the hospital a few months ago. Piumi Mark had food poisoning.

“We didn’t have fuel to [get to the hospital] in our own car, so we were struggling for a good three hours to find a cab.”

“We didn’t have fuel to come in our own car, so we were struggling for a good three hours to find a cab,”Piumi Mark said on a recent afternoon.

She and Alexander Mark were having an afternoon drink at a seaside Colombo hotel with their 6-year-old daughter Kendra in tow.

Alexander Mark called the situation hopeless: “We have vehicles at home. We have money to buy fuel, and we can’t,” he said. “There’s nothing you can do. It’s a very bad feeling.”

Nationwide gas shortages have left their car stuck in the garage. They can’t even take their daughter on vacation over her school break and have delayed trying for another child because of the crisis.

Self-described “foodies,” the family used to frequent Colombo’s best restaurants. Now, they eat at home and have cut down on their food consumption to combat a ballooning grocery bill.

“For us, we have cut down a lot,” Piumi Mark said. “But for [our daughter], we try to give her as much as we can.”

Their recent drink at a hotel — in a combined trip to central Colombo that included work meetings and a family visit — was the first such treat in months.

“The current situation is horrible. Even we are feeling it, ” Alexander Mark said. “So, we always feel, ‘What about the others who can’t even afford what we can afford?’”

Postwar economic growth

Sri Lanka’s postwar economic growth was built on consumption and debt spending on public infrastructure projects, economist Wijesinha said.

When the pandemic hit, tourists stopped coming to the country and remittance payments declined. The COVID-19 crisis, combined with ill-timed tax cuts, an import ban on fertilizers and risky fiscal policy, all left the country unable to pay its bills.

Then in May, the country defaulted on its debt. Inflation was at 61% in July, and now, the country doesn’t have enough currency in reserve to import basic necessities, creating widespread shortages of food, fuel and medicines.

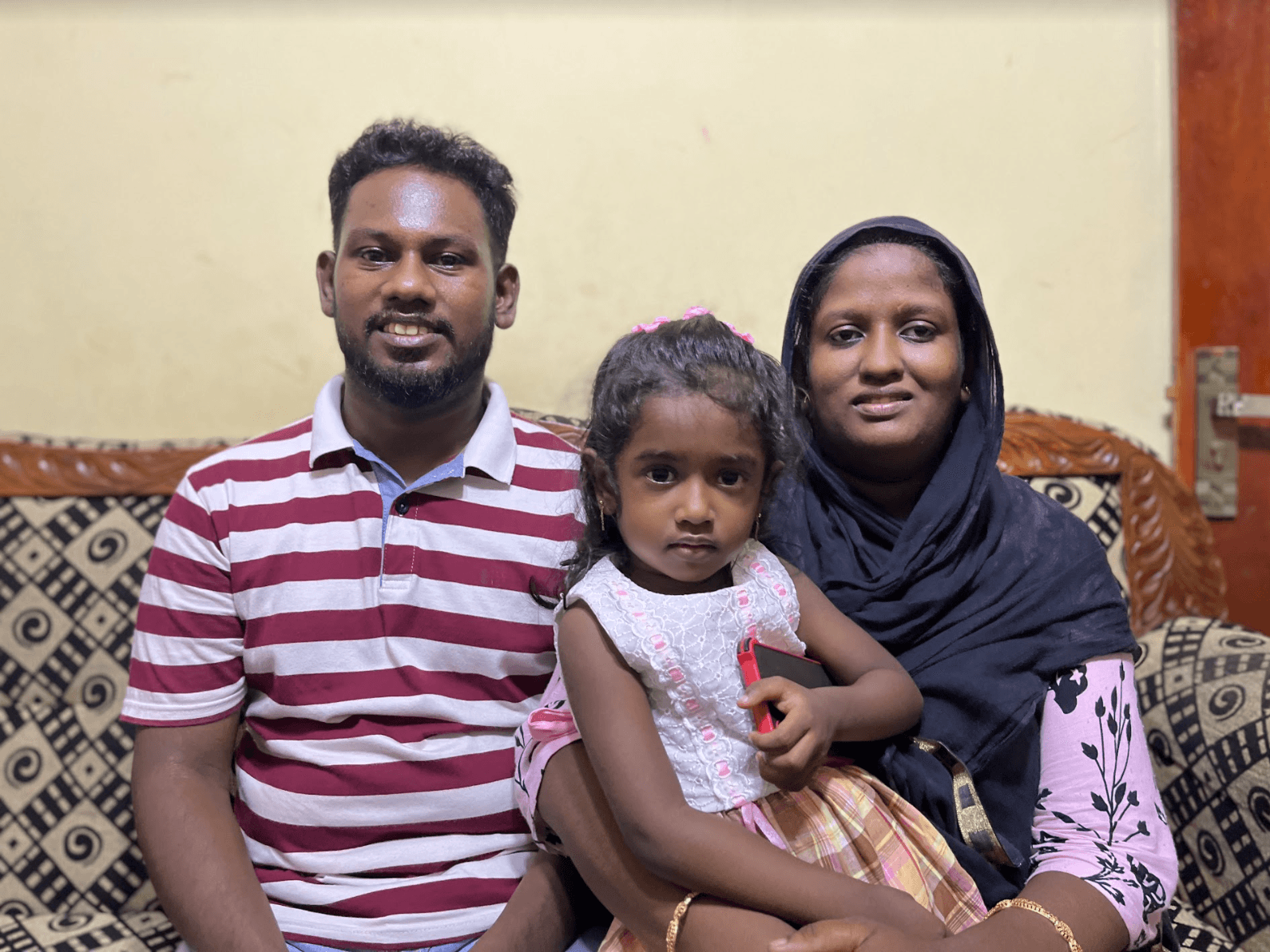

Mohammed Safry’s employment history tracks the country’s economic trajectory.

Mohammed Safry lives with his parents, wife and 3-year-old daughter in a two-bedroom home in the suburbs of Colombo. His mother has a garden out front, and his daughter likes to practice the alphabet with posters hanging up in the hallway.

Before the pandemic, Mohammed Safry was a chauffeur. And when tourists stopped coming to Sri Lanka, he traded in his car for a motorbike — to start making food deliveries. But by July, he was unable to reliably get gas for his motorbike, so he bought a bicycle instead. That’s cut in half the deliveries he’s able to make.

While biking around the city, he said he’s doing mental math on his family’s income and expenses.

“If I’m riding my bike, I’m thinking, ‘What are we going to eat, how much can I earn?’” Mohammed Safry said from the couch in his living room.

Until this year, the family could buy whatever groceries they wanted and still have enough left over at the end of the week to go out to dinner, or do something fun.

But since the economic crisis started, it’s become a struggle just to put enough food on the table.

“Before I wasn’t worried about food,” Mohammed Safry said. “Now, I’m worried. Very worried.”

Before the economic collapse, the shoebox-size basket of produce in the family’s fridge on a recent day would have cost between 200 and 300 Sri Lankan rupees, less than a dollar at today’s exchange rate, Mohammed Safry said. Now, they’ve had to pay 1,700 rupees, or about $4.50.

The government’s official inflation rate for food in Colombo is 91% year-over-year in July, but many residents report grocery bills that have far outstripped that increase.

Plus, today, Mohammed Safry can only afford to buy his parents’ medications a few days at a time.

Cooking over firewood

Because there’s a cooking gas shortage nationwide, Mohammed Safry’s wife, Fathima Rukaiya, had to start cooking over a woodfire in their backyard.

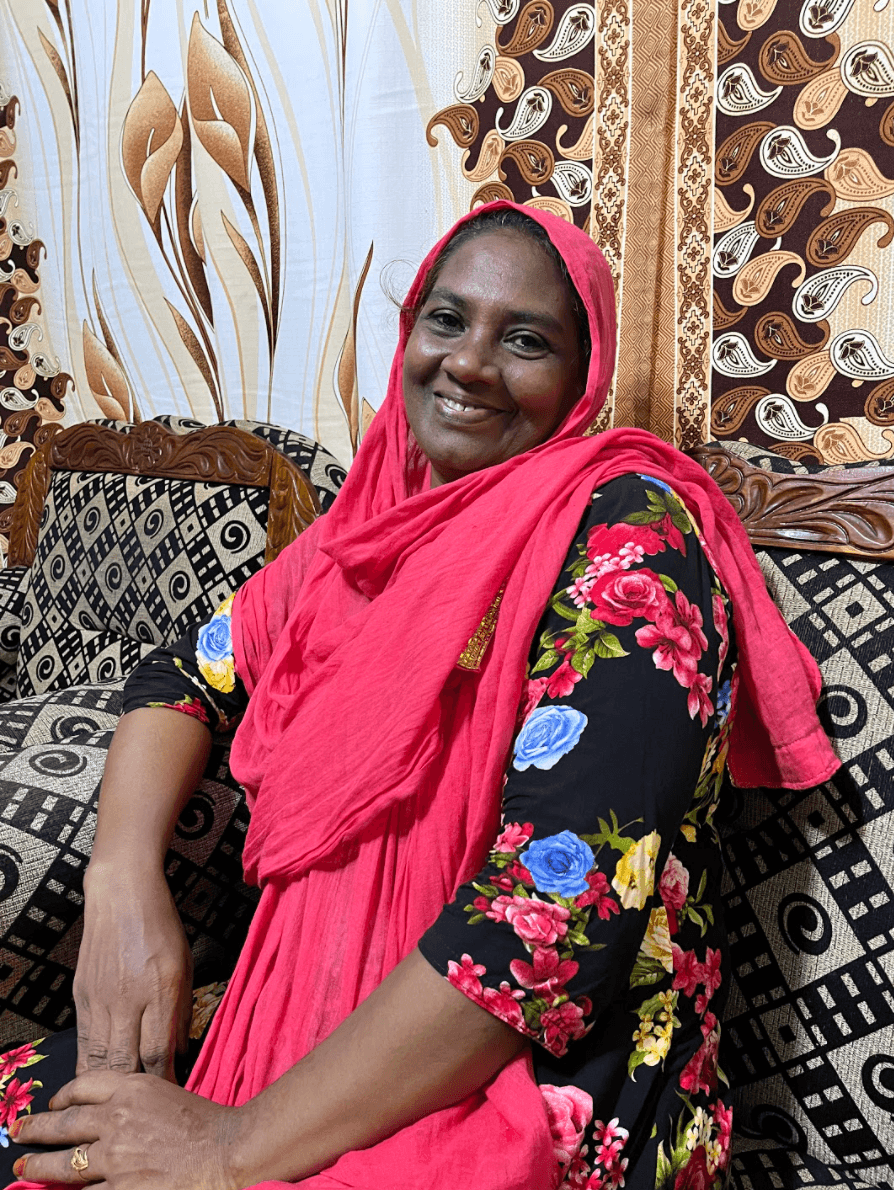

“When I was little, I saw my mother cooking on a wood-fired stove,” Faiza Safry said through an interpreter. “I never in my wildest dreams thought that this would happen, that the country would go backward like this.”

Also, the family worries about the Safrys’ daugher’s future.

Fathima Rukaiya hoped to eventually send her 3-year-old, Sara, to the fee-based school she attended, but now doesn’t know if that will be possible.

And she has a more fundamental concern.

“When we were young, we enjoyed life,” Rukaiya said through an interpreter. “But now, it’s very difficult to see how the children can enjoy anything. I’m angry that the situation has come to this.”

The road out of this crisis lies through a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund, which may take several months to finalize. It will almost certainly require Sri Lanka’s government to enact fiscal measures that will squeeze families like these even more.

“There’s a sense of dread,” economist Wijesinha said, wondering if it’s going to actually get worse before it gets better. “How quickly is that going to happen? Do we have what it takes to turn it around?”

Related: A community kitchen in Colombo feeds Sri Lankans in need