Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has affected every aspect of society, including the country’s health care system.

Widespread drug shortages have left patients and doctors pleading for donations online and resorting to second-choice treatment regimes. More than 100 medications and medical supplies are in shortage across the country, according to the Sri Lankan Ministry of Health, including the rabies vaccine and saline bags.

Sri Lanka imports at least 80% of its drugs and medical supplies, and the economic crisis has left it with inadequate foreign reserves to pay for them.

The problem caused widespread concern starting in March, when the country completely ran out of many common medications, including chemotherapy drugs and heparin, a blood thinner widely used during surgery and to prevent clotting.

Dr. Anver Hamdani, who since April has been charged with addressing the drug shortages for Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Health, said that 14 vital items and 312 essential items went out of stock. His office started to solicit donations from international agencies, foreign governments and individuals, in the form of cash, drugs and medical supplies. And though the situation improved, hundreds of items still remain in short supply.

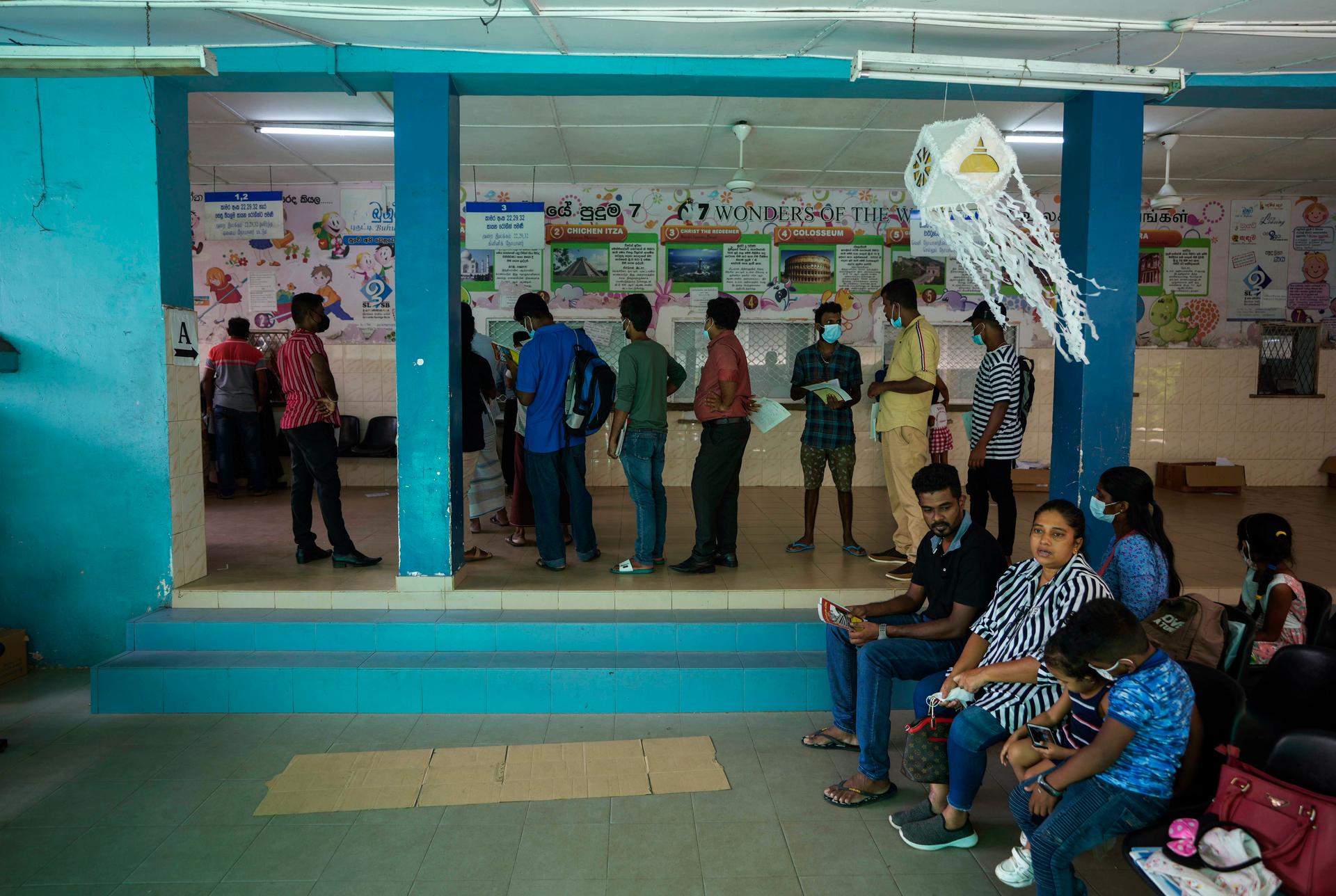

Private pharmacies are stocking fewer drugs. At government pharmacies, where drugs are free for customers, some medications are simply out of stock.

Colombo resident Kamaldin Soodin said that the three prescriptions his wife needs are no longer available at the government-run pharmacy where he usually goes, so he has to pay for them at a private pharmacy now. He can only afford to buy enough medication for two weeks at a time.

Meanwhile, Rageesh Wellalage, an anesthesiologist in southern Sri Lanka, explained that his hospital is out of two common IV antibiotics and is running short on catheters and suture materials — sterile surgical threads used for stitches — prompting them to ask patients to provide their own.

“We have to ask the patient to get the suture material from outside,” Wellalage said, including patients who need a C-section to deliver a baby. “Otherwise, we can’t start the Cesarean section.”

The country’s fuel crisis is causing similar challenges. One man outside a hospital in Colombo said that he had to find the fuel for an ambulance to transport his son after a serious motorcycle accident. His son’s leg ended up needing to be amputated.

Fuel shortages are also preventing or delaying doctors, nurses and technicians from getting to work.

Shaheem Fazmi said he waited all day at a clinic in Colombo seeking treatment for injuries sustained in a crash because his doctor was hours late.

“We need a certain number of staff to run an operation theater,” said Dr. Thilina Kannangara, who works in the northern district of Kilinochchi and spoke on behalf of the Government Medical Officers’ Association, a union representing most of Sri Lanka’s doctors.

When the staff doesn’t have gas, he said, routine surgeries get delayed.

“Let’s say usually [for a surgery] [what] we can do in one week’s time, we might have to wait two weeks.”

According to the doctor’s union, some hospitals have put nonemergency surgeries completely on hold.

According to the Ministry of Health, about a quarter of the country’s drugs and medical supplies are now coming in as donations.

“Running a national health care system on donations is only a temporary short-term fix,” said Vasan Ratnasingam, a spokesperson for the doctor’s union

He worries that if global goodwill dries up, Sri Lanka’s entire health care system will be in “severe crisis.”

Related: Amid fuel crisis in Sri Lanka, bicycling is no longer a ‘poor person’s mode of transport’