Massive sinkholes appear in farmers’ fields in central Turkey due to climate change and drought

A few weeks ago, in a cornfield just outside Cafer Ata’s house, the earth opened up. A round, sharp-edged sinkhole, about 10-feet deep, now stands in the ground as if cut by a knife.

Ata, a sheepherder, shakes his head incredulously. Although sinkholes have randomly appeared in central Turkey’s agrarian breadbasket in the past, they’ve started to show up with alarming frequency.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” he said in Turkish. “It’s bad. God have mercy.”

Sinkholes are a global geological phenomenon with many causes, but the recent uptick in Turkey’s central Konya region is largely attributed to rapid groundwater loss as farmers tap deep underground wells to irrigate fields amid a nearly three-yearlong drought.

Related: Drought in Iraq and Syria could totally collapse food system for millions, aid groups warn

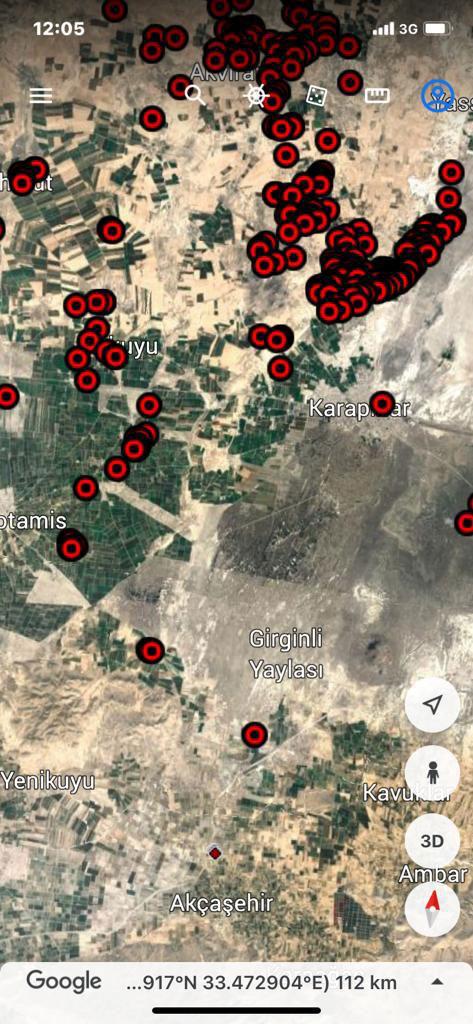

Researchers have cataloged more than 2,200 sinkholes in the area — more than 700 of which are deeper than 3 feet. The largest are hundreds of feet deep.

Back at Cafer Ata’s home, his wife Atiye Ata serves cups of strong, sweet tea.

Cafer Ata said he knows of at least one neighbor who fell into a sinkhole. It took two days to get him out. Sheepherders now must keep a mental map of each sinkhole, so their animals don’t fall in while they’re grazing in open fields.

Atiye Ata said that the past three years have been so dry that it’s hard to find green pastures at all.

“We keep buying hay from the market,” Atiye Ata said.

Every year, they sell some of their flock to buy animal feed, reducing their profits. It’s not a long-term fix.

“We can go hungry, but we won’t let our animals go hungry,” Cafer Ata said.

The winter landscape surrounding the the Atas’ home is a mix of dry, parched browns and swaths of deep emerald green, framed by distant mountains.

Just off the road in front of the village, a fenced-off sinkhole measures about 3-feet deep.

The area historically grew much of Turkey’s wheat, but farmers later shifted to more water-intensive crops like sugar beets and corn.

Those who can afford it install underground water pumps to irrigate their fields, but the area’s groundwater is limited. Every year, particularly in times of drought, they find themselves drilling further to reach the water. In doing so, they prime the ground above for a looming collapse.

Related: ‘The sea is throwing up’: Turkey’s record sea snot outbreak signals severe underwater pollution

“In the Konya Basin, there are 35,000 registered, legal pumps that pull up groundwater for irrigation. There are three times as many illegal, unregistered ones.”

“In the Konya Basin, there are 35,000 registered, legal pumps that pull up groundwater for irrigation. There are three times as many illegal, unregistered ones,” said Fetullah Arık, a geologist and director of the Sinkhole Application Research Center at Konya Technical University.

“This means that the groundwater is practically running out,” Arık said.

In an open field surrounded by industrial parks, Arık pointed out various types of sinkholes across the ground. The tiniest could easily be mistaken for an animal’s burrow. Others are modest and rounded, from the size of a watermelon to one that could fit a large bathtub. Some sinkholes appear suddenly — others start small and grow slowly.

Related: Seed keepers in Turkey revive old farming methods to confront new climate threats

Learning to predict sinkholes

Arık and his team are developing ways to predict where sinkholes will appear, using ground-penetrating radar and soil samples. Some sinkholes grow along underground fault lines that can be measured and studied.

“We can also tell in residential areas: If there are tiny cracks on door frames or the garden stairs, it can be an indicator of sinkhole changes. This way, we can mostly predict where they will appear,” Arık said.

By developing risk maps and cataloging their findings, Arık is trying to make the case to business owners and government representatives that sinkholes aren’t just a threat to farmers.

One field, for example, is a former marsh, drained to make way for factories. Each one could have structural problems if a sinkhole appeared beneath it. No confirmed fatalities related to sinkholes have yet been reported, but property damage is an issue.

“Even if there’s a small sinkhole in a field, it’s really difficult to find anyone to work there, or to find agricultural machinery to work there. They’re afraid that something could happen,” Arık said. “It’s a significant economic loss.”

Longer droughts, higher temps

The problem seems to be mounting.

Climate change predictions for central Turkey include longer droughts and higher temperatures. Last year, Turkey’s wheat production fell by 14%, according to the Turkish Statistical Institute. Even red lentils had to be imported, after a 30% loss.

Still, farmers in the Konya area insist that they must pump water from wells in the ground.

In a village outside the town of Karapinar, an area with one of the highest concentrations of sinkholes, dairy farmer Mustafa Baldanoğlu said that in his childhood, the town would get plenty of rain.

But today, after almost three years of drought, they rely on the wells to grow animal feed.

“We used to draw water from 20 meters down. Now, it’s from 55 [meters] to 60 meters below,” Baldanoğlu said.

Sinkholes appear in the village with relative frequency, but neighbors say most are small enough to be repaired.

Baldanoğlu supposed that water could be piped in from the neighboring towns, but that would also have to come from groundwater.

“There’s no alternative,” Baldanoğlu said.