Chileans have long struggled with a water crisis. Management practices are partly to blame, study says.

Chile has been facing a megadrought for more than a decade, with central regions receiving 30% less rainfall than usual over the past 13 years.

Around 8% of Chile’s population does not have access to clean drinking water or proper sewage systems, according to the Chilean Ministry of Social Development.

For years, people believed that climate change was to blame. But a recent study published in the Switzerland-based journal Water found that this shortage was not only due to the megadrought, but has also been caused by water misuse and management practices established under the country’s current legislation.

Related: Why Chile moved ahead with COVID vaccines for the very young

That includes the process of diverting water sources away from populated areas toward crops instead — like avocados — that require a lot of moisture to grow.

Veronica Vilchez, a farmer who lives in the area, said that a truck delivers between 20 and 40 liters of water a day for her family. That’s only enough for each family member to take a two-minute shower.

This is despite a court ruling from March 2021 that set a minimum of 100 liters per day per person for Petorca.

“We don’t have people here who enforce the ruling,” Vilchez said.

She added that she lives with five other family members and that they all have to find creative ways to reuse the water multiple times.

“I clean the floor with the same water I use to wash my hair, do the dishes and water the plants,” she said.

“Our horses, cows, sheep, they are all dying. Schools are closing and people are moving away because there is no water.”

“In Petorca, it smells like death,” she said. “Our horses, cows, sheep, they are all dying. Schools are closing and people are moving away because there is no water.”

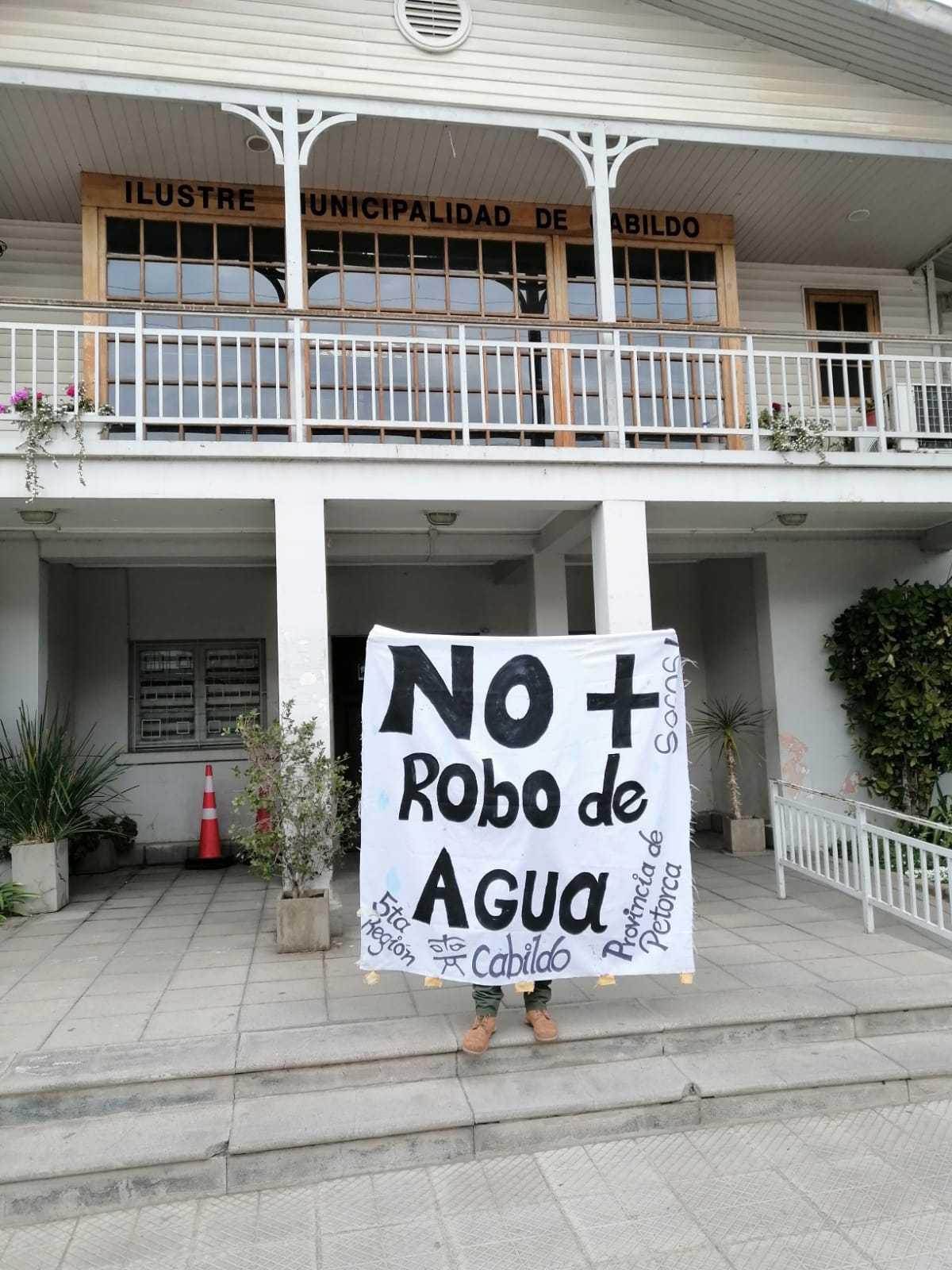

Vilchez is part of the organization Mujeres Modetima, a group of women activists who deliver water to nearby communities. But while people are suffering from severe water shortages, she said that she can see, from her window, rows of green trees from the avocado plantations covering the hills nearby.

Related: Electricity rates have skyrocketed in Brazil. The govt says the water crisis is to blame.

As a major avocado exporter, Chile produces nearly 220,000 metric tons of avocados per year, and the majority of them grow in Petorca. Avocado producers pump thousands of liters of water per second to irrigate the area, according to Chilean hydrologist Pablo Garcia-Chevesich, a professor at the University of Arizona.

He said that Chile is one of the few countries in the world that allows full privatization of water.

“Just because a water course is flowing, in Chile, you can get the water rights from a river, and they give it to you for life, for free,” he said. “And then you can [divert] that river and use it [for] your convenience.”

It’s a water code that goes back to the early 1980s under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Now, 90% of the country’s fresh water rights are held by private companies.

Related: In Mexico, shuttered cemeteries mean financial ruin for thousands of flower farmers

Chile’s economy, being the largest in South America by per-capita gross domestic product, is built on water-intensive, extractivist industries, principally mining and agriculture.

So, García-Chevesich discovered that the root cause of Chile’s water crisis is overconsumption of water by the agriculture and mining industries, not climate change.

“The pattern is the same: A big exporting company arrives, takes all the water rights, drills very deep wells, [diverts] the rivers, and that means the aquifers deplete, the rivers dry out and the farmers don’t have any more water,” he said.

“The final purpose for the freshwater is to create profit, not to provide welfare for citizens.”

“The final purpose for the fresh water is to create profit, not to provide welfare for citizens,” he added.

Meanwhile, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric is now proposing a new constitution that would prioritize water for human consumption. It would also allow the government to suspend the rights of usage on threatened water sources.

But the plan needs a two-thirds majority in Congress to pass before it can be put to a national referendum for voters to decide on.

Garcia-Chevesich said that while deprivatization of water is a long overdue policy in Chile, it won’t solve the existing water emergency: “We will have to look at different sources of water, like [conducting] desalination, for example.”

He also said the country urgently needs an education program about the water crisis as well as a national ration plan.

In April, the governor of Santiago, Claudio Orrego, did announce a possible four-tier alert system to ration water to the city of nearly 6 million people.

Related: Iran’s ‘system is essentially water bankrupt,’ says environmental expert

“We’re in an unprecedented situation in Santiago’s 491-year history where we have to prepare for there to not be enough water for everyone who lives here,” Orrego said.

The four stages of the proposal, which hasn’t been implemented yet, will be based on the capacity of the Maipo and Mapocho rivers. The process will begin with public service announcements, moving onto restricting water pressure and ending with rotating water cuts of up to 24 hours.