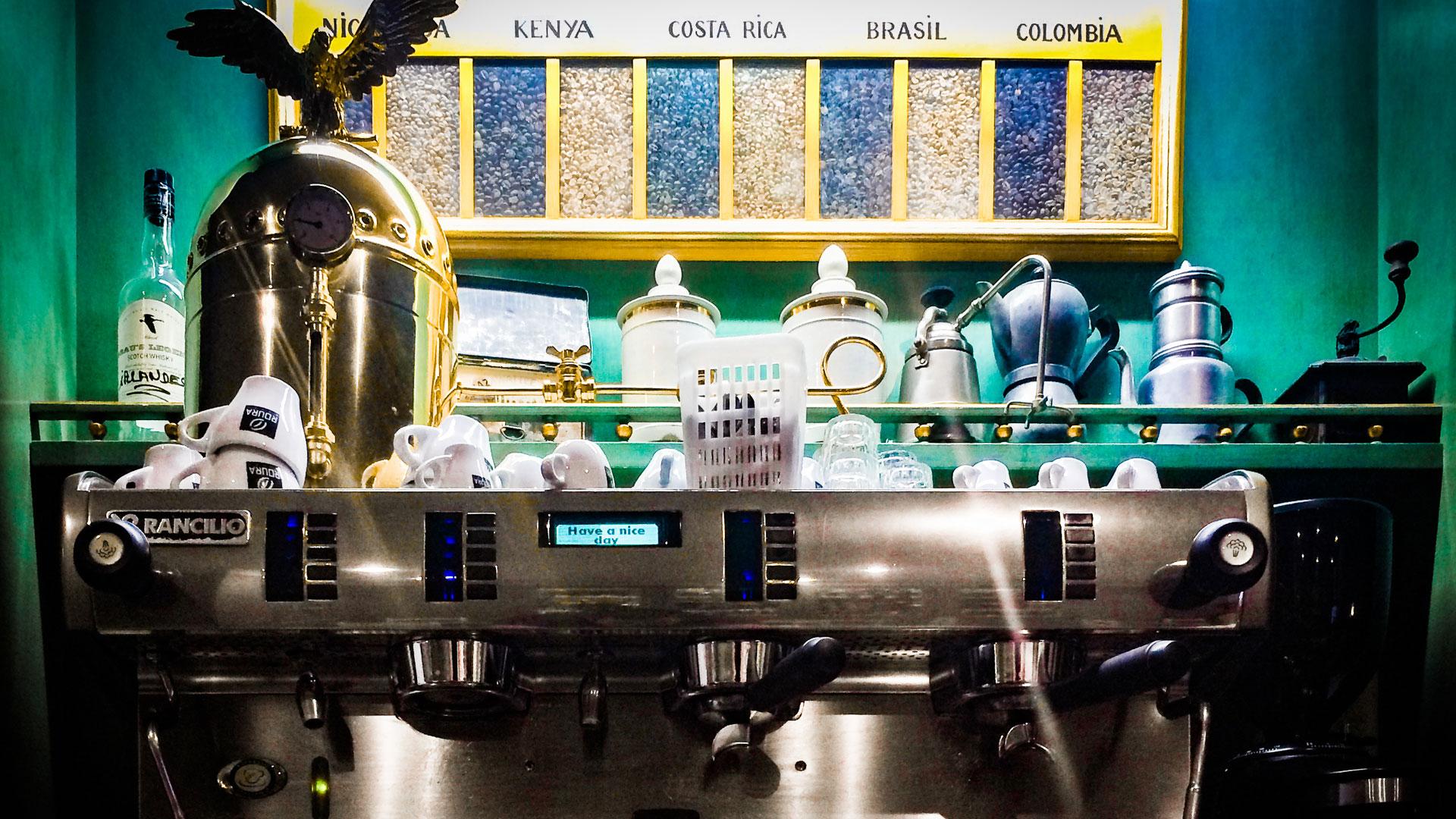

It’s a typical weekday afternoon at Red Emma’s coffee shop in Baltimore, Maryland. A handful of people sit chatting over wooden tables in the large open dining area.

Behind the counter, barista Najee Haynes-Follins makes an iced Americano at the machine. She’s a member of the worker’s co-op that owns and runs the coffee shop, restaurant and bookstore.

“What do I love about coffee?” Haynes-Follins asked. “I have ADHD, so stimulants are useful to me and so if I’m gonna focus in the morning, I’m usually drinking a cup of coffee in order to keep me a little bit in line.”

She said Red Emma’s coffee prices have stayed roughly the same recently. But that it might not be for long, due to a major glitch in the global coffee supply. Brazil, the world’s largest coffee exporter, was hit by unprecedented extreme weather that seriously damaged coffee crops — which may ultimately drive up the cost of coffee around the world.

In late July, southern Brazil was hit by uncommon freezing temperatures. Snow blanketed many hillsides. In coffee-growing regions, frost covered the fields. In one video shared online, a farm worker inspects coffee plants that have been devastated by the frost in the state of Minas Gerais. The leaves are dead and brown. The coffee beans are black and encased in ice.

“On this property, we have lost 80% of the coffee crops,” coffee grower Flavio Figueiredo said. “In this region, I think 30 to 40% of the coffee plants have been damaged.”

Coffee producers estimate that almost half a million acres of coffee crops were hit by the frost. It was the worst Brazil has seen in 27 years.

“This is a really difficult year. … We haven’t seen anything like this in a long time. But we believe we are adjusting so that next year our harvest isn’t as bad as people are projecting.”

“This is a really difficult year,” said Celírio Inácio, the head of the Coffee Industry Brazilian Association. “We haven’t seen anything like this in a long time. But we believe we are adjusting so that next year our harvest isn’t as bad as people are projecting,” he said.

Brazil’s coffee crops weren’t just hit by the frost. They were also crippled early in the year by drought.

People in the industry worry that climate change will create more extreme weather events like these, making coffee production more and more unpredictable.

Related: ‘Where’s my stuff?’ Here’s why global supply chains are out of whack due to pandemic

“We have to be thinking about this. It’s really in our face, it can’t be ignored,” said Nani Ferreira-Mathews a part-owner of Thread Coffee roasters, another co-op in Baltimore, which supplies to Red Emma’s.

“The top two coffee-producing countries are Vietnam and Brazil, and if either of those two countries have any sort of weather issues or supply issues, it will affect the entire world market. We saw that in the ’90s and again now.”

“The top two coffee-producing countries are Vietnam and Brazil, and if either of those two countries have any sort of weather issues or supply issues, it will affect the entire world market. We saw that in the ’90s and again now,” she said.

In July, the coffee market price spiked to a seven-year high. The price of coffee futures now stands at about $1.93 a pound, up 50% from the beginning of the year.

Related: Backlash from bubble-tea fans after China bans plastic straws in restaurants

Ferreira-Mathews said you might not see a rise in prices at your local coffee shop just yet. Right now, the coffee circulating now was harvested when prices were low. But that is not going to last.

“I really do think we are about to see a very significant change in prices at cafés, because of the pandemic, paired with what will be a supply shortage coming out of Brazil,” Ferreira-Mathews said.

Related: ‘Drought has severely impacted livestock keepers’ in Afghanistan

Pandemic lockdowns upset worldwide trading systems, causing merchants all kinds of headaches.

“We are having export problems with the shortage of shipping containers, and now the much higher costs for ocean freight. This also brings uncertainty.”

“We are having export problems with the shortage of shipping containers, and now the much higher costs for ocean freight. This also brings uncertainty,” Inácio said.

Some larger companies, like Starbucks, said their prices will remain stable for the next year, because they purchase coffee beans 12 to 18 months in advance.

Meanwhile, many in the Brazilian coffee industry are concerned, not just for this year, but for the next, as it could take Brazilian coffee growers months — potentially years — to get back on their feet, if some plants have been permanently damaged.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on The World. Please take our 5-min. survey.