When the Chinese government banned the use of disposable plastic in restaurants this year as part of its newest five-year plan, it unwittingly attracted criticism from a very vocal group — bubble-tea drinkers.

That’s because when drinking bubble tea, the straw is essential. How else can you suck up all those chewy tapioca balls?

Related: China announces a new ban on single-use plastics

Most restaurants and cafes in China were using conventional polypropylene straws before the ban, and they made the switch to paper straws en masse.

But customers were having none of it.

Paper straws are no good, said Xiao Cao, while sitting with his girlfriend at a trendy tea shop in Shanghai, drinking his daily cup of bubble tea. If you use them for too long they get all soggy. It affects the taste, he said.

Bubble-tea chains quickly offered up another straw option, made from PLA, a plant-based bioplastic. But the complaints from bubble-tea drinkers had already started a national conversation about straws.

Related: Bahamas Plastic Movement founder wins Goldman Prize

China has been tackling its waste problem over the past decade. They banned waste imports from the US and other Western countries, and in 2019, they piloted a waste-sorting scheme to separate food waste from other waste.

But landfills and incinerators are still overused.

Related: China’s ‘Operation Empty Plate’ targets food waste

Zhang Miao, founder of a nongovernmental organization focused on waste reduction, says the ban on disposable plastics has created a loophole, and now sales of PLA bioplastic are way up.

Yes, PLA is technically biodegradable under certain conditions, she said, but most people can’t tell it apart from conventional plastic and they just end up in the trash together, so the problem isn’t solved.

Recycling also lacks infrastructure, she said. She recommends government support for the development of a formal recycling system to get a better handle on plastic waste.

Manufacturers have a role to play, too. The World visited a straw factory in Yiwu, a city near Shanghai, to see how the ban has impacted their business.

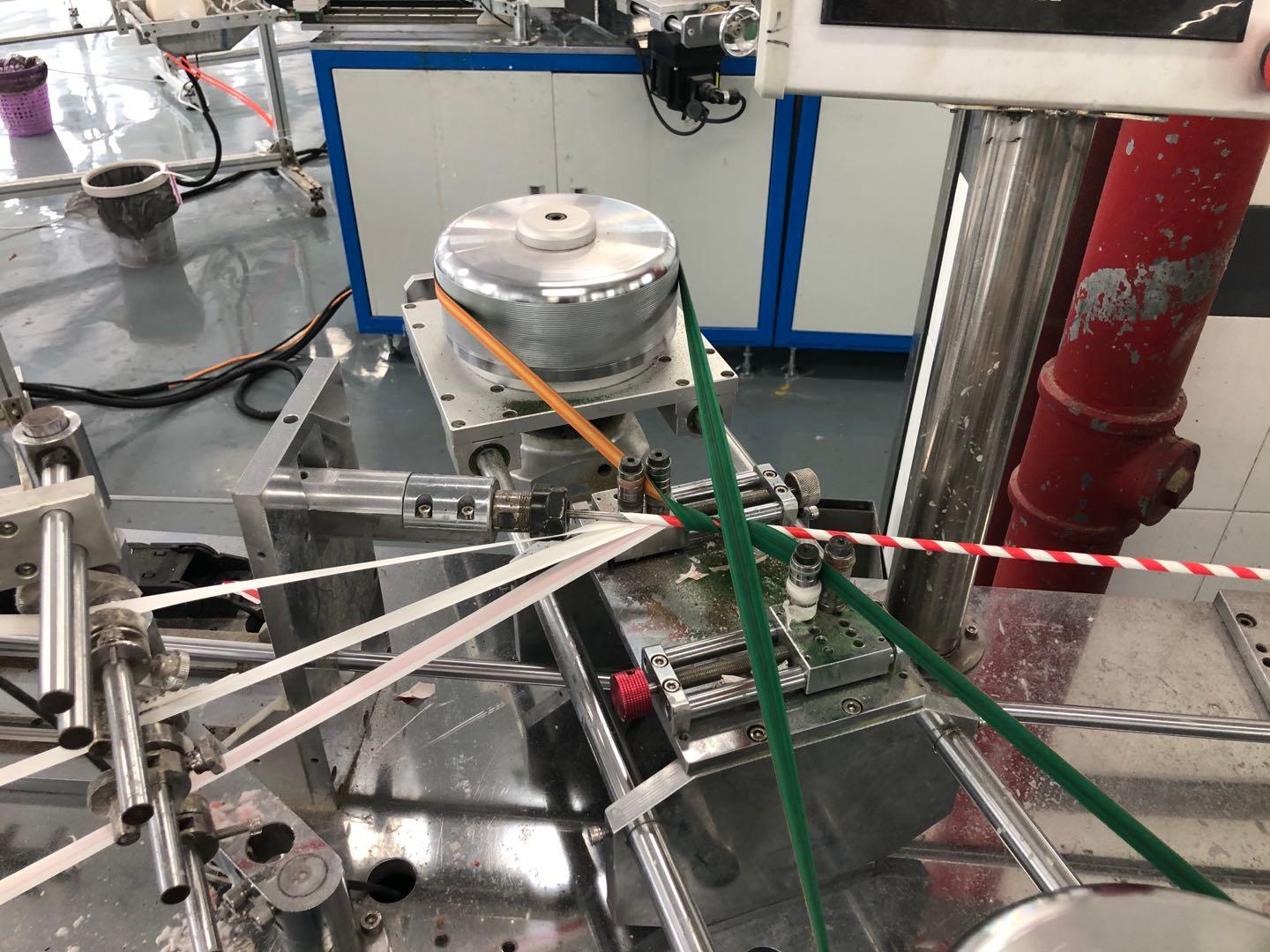

On the factory floor, machines spew out colorful straws as workers collect and bundle them into boxes. But instead of producing conventional plastic ones, now they mostly make paper and PLA straws, instead.

Factory worker Yun Lei works on three machines at once. As reams of red and white paper ribbons pass through the machine, they’re dipped in glue and wrapped around a metal dowel like a candy cane, and then cut into straw-length pieces. Yun waits until the straws pile up and then packs them into boxes, handling as many as 300,000 straws a day.

Factory tour guide Lou Zhongping, known in these parts as the “King of Straws,” said that after the plastic straw ban, his business is doing better than ever. Lou is the chairman of Soton Straws.

Lou was a member of the study group that recommended the government ban on disposable plastic straws.

There’s always going to be a market for straws, but the industry has to push for change, he said.

Last year, during the pandemic, Lou replaced his machines with new ones to make paper and PLA straws. And he made another switch — he dropped his export business, for the most part, and focused on the China market instead.

Production is now up, and because the cost of these new materials is higher than conventional plastic, he can charge more, too.

Lou heads to the showroom, full of reusable straws made of metal, heavy-duty plastic, bamboo, wood, glass and even some made from wheat stems.

It’s not that plastic straws themselves are bad, Lou said, just the way we use them. Still, his research team is trying different materials to wean people off their disposable habits.

One straw made from corn and pumpkin starch is colorful, he said, and edible, too! They taste like raw pasta and last an hour in cold drinks, he said, chewing on one to demonstrate.

But there’s a design flaw — the straws will melt in a cup of hot bubble tea.

Environmentalist Zhang Miao said there are no easy solutions.

More people are paying attention to plastic waste, she said, but customers are so used to cheap, and convenient plastic that it’s going to be hard to change habits.

The Chinese government carries on, with plans to ban plastic bags and disposable plastic in hotels in the years ahead.