After coal: A new book and documentary chronicle ‘stories of survival in Appalachia and Wales’

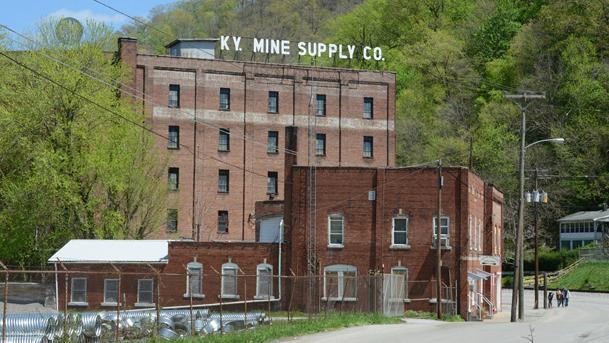

A Kentucky Mine Supply building in downtown Harlan, Kentucky. Many communities in Appalachia are struggling as coal production decreases.

Coal-producing regions in both the United States and the United Kingdom have been hit hard economically as coal production has dropped, leaving miners out of work and their communities with shrunken tax bases and fewer paying customers for local businesses.

These communities are the focus of a new book and documentary by Tom Hansell, called “After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales.” The book and the film tell the story of the After Coal Project, an initiative that seeks to bridge former Appalachian and Welsh coal mining communities.

Hansell writes about the need to support these communities and help them prosper, especially in this time of climate crisis, he says. Coal production has been declining for years and now many more communities could get left behind in the transition to a green energy economy.

“I believe that the only way to get deep and lasting solutions is to reach out first to people that have been part of an extractive economy, whether that’s the oil fields or the gas fields or the coalfields.”

“Obviously, we have to address the climate issue. That’s what the science tells us — and it’s crucial to do it sooner rather than later,” Hansell says. “At the same time, I believe that the only way to get deep and lasting solutions is to reach out first to people that have been part of an extractive economy, whether that’s the oil fields or the gas fields or the coalfields.”

Related: Spain’s coal miners continue to wait for their country’s ‘Green New Deal’

Communities that have been built up around a single industry need other options and perhaps extra support — particularly in the case of the coalfields, Hansell argues.

“The coalfields powered the United States for most of the 20th century,” he says. “There was coal that helped us win world wars; there was coal that helped build the strongest industry and economy in the world. And very little of that wealth was left behind. Most of that wealth went to corporations that were headquartered outside of the coalfields. There needs to be some system where some of that wealth gets returned and some of the opportunities that coal provided to the nation get returned and focused back in the coalfields … It’s really crucial to bring the most vulnerable populations along.”

Related: Britain built an empire out of coal. Now it’s giving it up. Why can’t the US?

One way to help restore these communities is through the support of local food and the arts, Hansell says. He was impressed at the amount of local farming that sprung up during the time of the After Coal Project. In a series of public forums Hansell conducted with local organizations to talk about what a green energy future might look like in their communities, people wanted to talk about farming, agriculture and local foods, he notes.

“It took me a while … to understand that when they were talking about diversifying the economy, that’s where they saw their assets,” he says. “Since that time, and even since … the After Coal Project was gone, local foods and local agriculture have really exploded in the coalfields.”

For example, he says, one former miner named Shane Lucas created a small farm on his family’s land that was connected with a network of farmers’ markets in Letcher County, Kentucky. That network has expanded and now includes a project in which the local healthcare agency uses some of its Medicaid expansion funds to offer “tokens,” in the form of prescriptions, for fresh vegetables from the farmers’ market. Patients turn in those tokens to local farmers like Shane Lucas and the farmers bring them back to the health care provider and get paid in cash.

“So, what you end up doing is dealing with issues like diabetes by increasing the amount of fresh vegetables [and] dealing with issues like economic development by supporting local farmers and supporting the local health care industry,” Hansell says.

In Branwen, Wales, Hansell spent time with the DOVE Workshop, an educational workshop with a small restaurant catering business and a childcare business housed in a former coal mine office. He found that unions were deeply involved in creating gathering spaces and providing continuing education services.

“There was a whole system of miners’ libraries and free courses after hours so that miners could continue their education and fully participate in civic life, which I thought was really interesting,” Hansell says. “And [there were] other kinds of cultural aspects of the unions, including male voice choirs or brass bands [that] are big things … in the UK.”

Likewise, in Appalachia, Hansell was able to work with the Southern Appalachian Labor School in Oak Hill, West Virginia. “They actually have taken over a former school in that town that had closed down due to school consolidation, and we did things like a fundraising dinner and film screenings,” Hansell says.

Hansell also created a music exchange, which brought musicians from Wales to the annual Seedtime on the Cumberland music festival at the Appalshop Media Arts Center in eastern Kentucky for a performance and a discussion, and sent performers from Appalachia over to Wales to their Hay Festival to do the same.

Hansell believes the exchanges between the communities have provided people a way to reflect and to brainstorm about the future. And while the per capita income in each place has not dramatically changed since the After Coal Project, he says the economies have diversified.

“I would say that both these conversations and the After Coal Project as a whole have increased the recognition of locally-driven organizations that are doing the work,” he says. “In terms of how it has participated in building a movement and supported the people that are in these communities on the ground doing the work — I feel pretty good about that.”

This article is based on an interview with Steve Curwood that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.