Educators in France advocate for better Holocaust curriculum

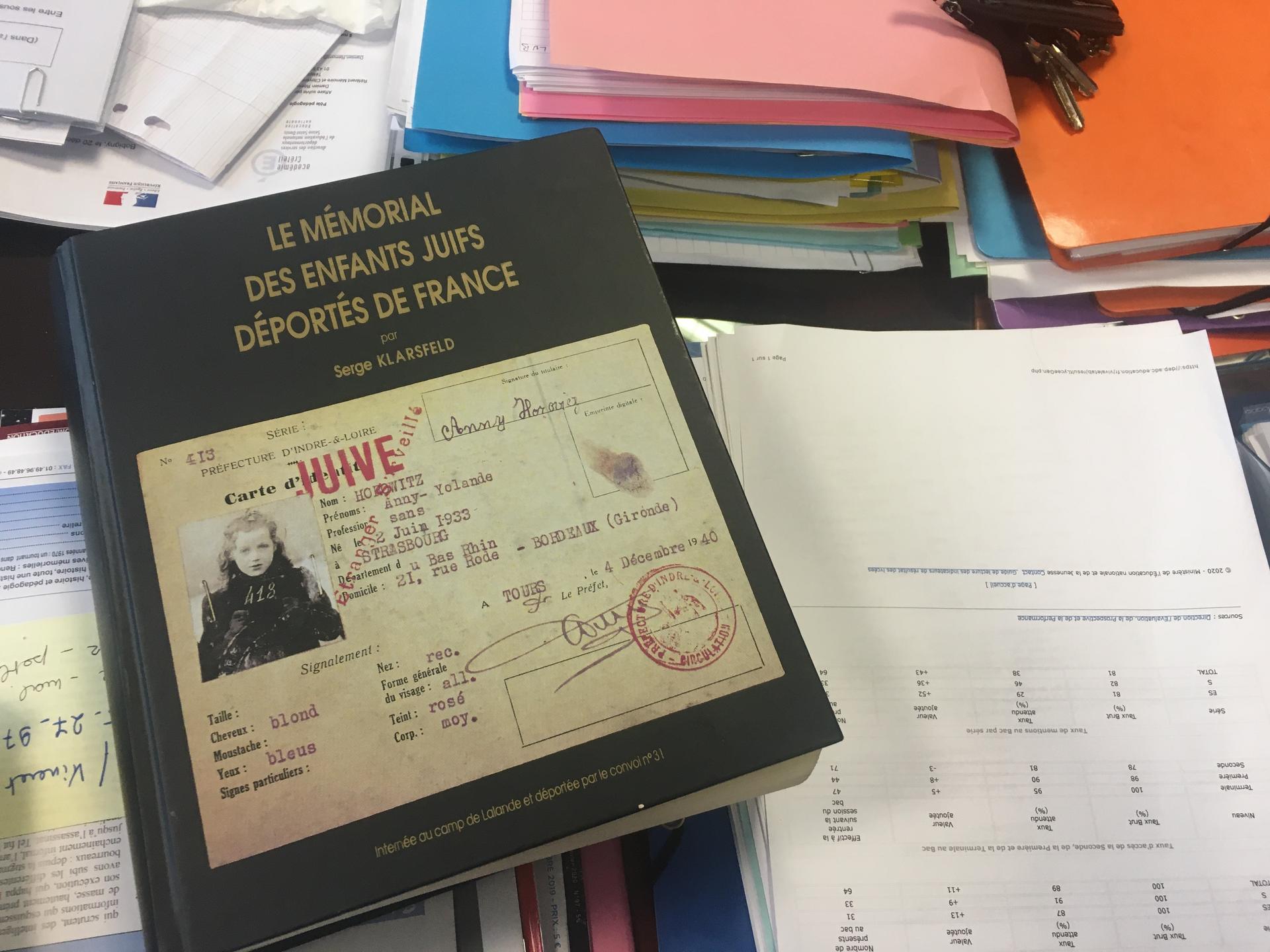

Around 11,400 children were deported from France during the Holocaust. Students at Alliance Pavillons Sous Bois will spend time tracing the history of individual child deportees as part of the school’s Holocaust curriculum.

“Does anyone know where the president is today?” history teacher Iannis Roder asked his students at Collège Pierre de Geyter, a middle school in the working-class Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis on Jan. 27.

“Is he in Iraq? The US?” some students asked. Roder shook his head. “Did nobody listen to the radio this morning?”

It was the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration and death camps in Poland, and French President Emmanuel Macron was paying his respects to victims and survivors at the Mémorial de la Shoah in central Paris.

Roder invited The World to join him in asking the students some more basic questions to test their knowledge of the Holocaust. Like, “Who here has heard of the Holocaust?” It seemed like a basic enough question.

Related: Protests continue in Paris amid pension reform debate

The radio silence that followed the question, however, suggested otherwise. Teaching about the Holocaust is required in French schools, but students often know very little about it, and as Roder can attest, filling that gap is no easy task. And with anti-Semitism on the rise in France, educators like Roder are calling for a better curriculum.

“We’ll have to rephrase it,” Roder said to the class. “What about the Jewish Genocide? Do you know what that means?”

Several students nodded. “Oh yeah, the Jewish deportation! I think I’ve heard of that,” one student answered as others nodded their heads in agreement. But when asked how many Jews died in the Holocaust, the confusion started all over again as the class shouted a chorus of guesses.

One boy responded in a joking tone, “1 million … 3 million … or what about 9 million.” Nobody gave the correct answer: 6 million.

“They don’t know anything about the Holocaust,” Roder admitted once class ended, and his students went out to recess. “They don’t speak [about the Holocaust] with their families.”

This isn’t their history, he said. Most students at this school are first-generation French, with families that come from North and sub-Saharan Africa such as Morocco, Algeria and Senegal.

Luckily for these students, Roder is a leading figure on Holocaust education in France. In March, his students will start a rigorous, 15-hour curriculum on the history of Nazism and the Holocaust. They’ll even spend time learning about France’s collaboration with the Nazis, something the French government denied until 1994. Roder said his curriculum goes far beyond the basic requirements of France’s National Education Ministry. “If I do what the program of the National Education Ministry says, [the students] will finish this year by not knowing anything.”

Related: France sets deadline to return 26 objects to Benin by 2021

In January, the US-based Claims Conference, an organization that fights for justice for Holocaust victims, published an alarming survey about French millennials’ knowledge of the Holocaust, which found that 25% of respondents either hadn’t heard of the Holocaust or weren’t sure if they had. Another 44% thought 2 million or fewer Jews were killed during the genocide.

Jacques Fredj, director of the Mémorial de la Shoah, says the survey fails to address the progress France has made in Holocaust education.

“We have about 100,000 kids coming to the memorial every year,” he said. The memorial works closely with the National Education Ministry to educate students and teachers about the Holocaust.

“We don’t have a problem with teaching the Holocaust in France because you know it’s mandatory. We have a commemoration, we have lots of interests, we have movies and a lot of books.”

“We don’t have a problem with teaching the Holocaust in France because you know it’s mandatory,” Fredj said. “We have a commemoration, we have lots of interests, we have movies and a lot of books.”

Today, France’s National Education Ministry requires educators to teach students about the Holocaust at four points during their education — in primary school, middle school and twice in high school. That mandate is far better than what is taught by certain European neighbors. In Italy, Holocaust education is only required in students’ last year of high school, and in Belgium, there is no required Holocaust curriculum in the Flemish-speaking part of the country.

Though, according to the same survey sponsored by the Claims Conference, 41% of respondents said France’s Holocaust curriculum could be improved.

While the Mémorial de la Shoah is responsible for training around 7,000 teachers every year, Roder estimates that the average teacher will only spend about two hours on Holocaust studies. Other teachers, he said — particularly in the working-class suburbs — may skip the curriculum entirely because they feel unprepared for how to answer questions from students who may cast doubts on the history of the Holocaust. Roder remembers dealing with this issue himself when he first started teaching 20 years ago. “I remember a student who said Hitler was a good Muslim, for example,” he said. “I don’t remember exactly what I did, but I was very shocked.”

A new challenge for Jewish educators

At a nearby, private Jewish school, teachers are tackling a different challenge when it comes to educating students about the Holocaust. To make up for the gaps in public school curriculum, Sarah-Laure Attias, the director at Alliance Pavillons Sous Bois, said the Jewish students here need to be extra prepared.

Related: France moves to make reproductive technology legal for all

“For us, it’s a matter of training our students so when they go out and meet people who aren’t Jewish, they can tell them with confidence that the Holocaust not only existed, but it was a universal problem — not a Jewish problem.”

“For us, it’s a matter of training our students so when they go out and meet people who aren’t Jewish, they can tell them with confidence that the Holocaust not only existed, but it was a universal problem — not a Jewish problem,” Attias said.

As the last generation of Holocaust survivors dies out, Attias said, the responsibility of students to carry on their message is more important than ever. Anastasio Karababas, a history teacher at Alliance Pavillons Sous Bois, specializes in Holocaust studies. His students will spend about 30 hours on the Holocaust this year, culminating in a visit to Auschwitz in Poland. At the end of their education, the students will also visit the Yad Vashem memorial museum in Israel. Karababas said he worries about France today, especially when he looks at posts on social media.

“We can read things like, ‘No 6 million … it’s not possible. Jews use those numbers to make war against the Palestinians or to impose their opinion around the world,’” he said.

Related: Young people in Poland are rediscovering their Jewish roots

A 2018 study from the World Jewish Congress found that conversations on social media denying the Holocaust had doubled compared to the same period in 2016. The study also found anti-Semitic posts had increased by 30%. In another survey from the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 95% of French Jews said they believed anti-Semitism on social media was a problem.

Back at the public school, Roder’s students ran out the door — all except for one who approached Roder with a concerned look on his face. “It’s not normal that we don’t know any of this,” he said, frightened by what he has just learned, but also by his own ignorance.

Roder reassured him that he will learn all this come spring. But in other French classrooms, the question lingers. What are French teachers and the French education system doing to make sure that “never again” does, in fact, mean never again?

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?