Don’t let your vote get stolen — 5 essential reads about disinformation in 2020

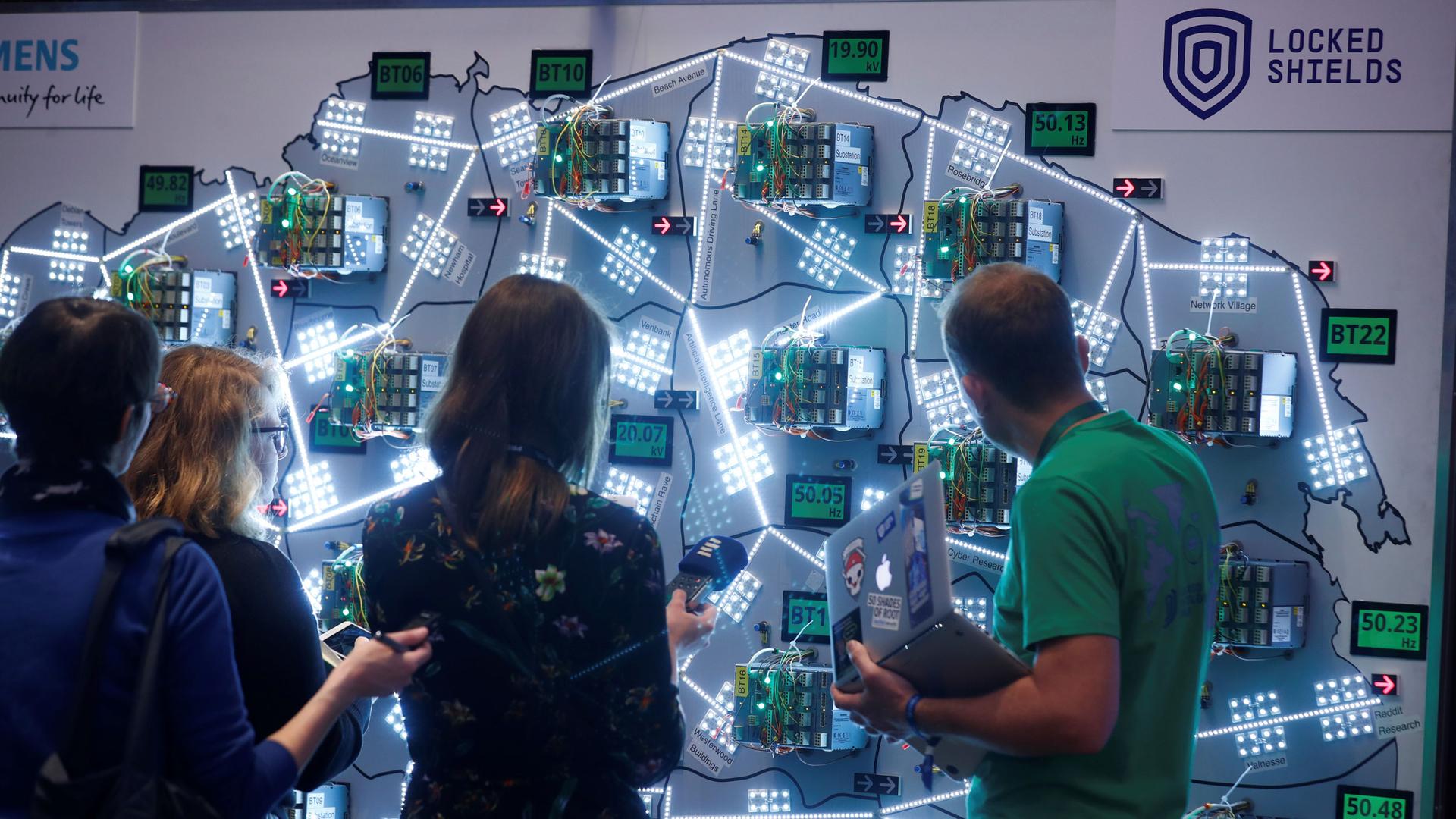

People look at the visualization during the Locked Shields, cyber defense exercise organized by NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, Estonia, April 10, 2019.

As the 2020 election season heats up, there will be a massive number of people competing for your vote. Only some of them will be legitimate candidates.

The vast majority will be information warriors, people who seek to confuse you about what is truth and what is fiction — the better to influence your thinking.

If you’re confused or misinformed, you may well vote in ways that serve their masters’ interests — or that simply sow further chaos and division in the US.

How do I know this? Because it happened in the US in 2016, and again in 2018 — and has been happening around the world.

Here are a few examples that authors for The Conversation have highlighted over just the past year — plus a couple of ideas about ways you might help protect yourself and your fellow Americans from information warfare.

1. Seeking influence in the Middle East

A propaganda arm of the Russian government publishes articles that appear on a leading Egyptian news site, reveals Nathaniel Greenberg, a scholar of Arabic at George Mason University.

The propagandists’ goal, Greenberg explains, is to make it more difficult for readers to tell the difference between propaganda and legitimate news reporting.

The effort “is part of a long-running Russian campaign to build influence in Egyptian media and elsewhere around the world — including in the US,” he writes.

2. Looking to the neighbors

Russia is also trying to influence European politics, writes Liisa Past of Arizona State University. She is a former Estonian government cybersecurity official who worked with her counterparts across the European Union to protect national and EU-wide elections.

As the 2019 EU Parliament elections approached, “hackers backed or controlled by Russia targeted EU government, media and political or nonprofit organizations,” she writes, including trying to hijack online accounts of “foreign and defense ministers across the continent.”

3. Learning from history

The people of the Baltic nations — Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia — have what may be the most experience fighting against disinformation campaigns. They’ve faced Russian propaganda efforts dating back to the 1940s, says cybersecurity scholar Terry Thompson from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

For decades, “the Baltic countries were subjected to systematic Russian gaslighting” — intentional misrepresentation of facts — “designed to make people doubt their national history, culture and economic development,” he writes.

Those countries’ solutions offer ideas for the US, Thompson suggests, “including publicizing disinformation efforts and evidence tying them to Russia. … The US could also mobilize volunteers to boost citizens’ and businesses’ cyberdefenses and teach people to identify and combat disinformation.”

4. It’s not just Russia

Lots of other groups are trying to manipulate voters’ minds in new ways. In the recent United Kingdom parliamentary elections, several political parties used what are being gently called “dirty tricks” to gain an advantage over their opponents, writes Cardiff University journalism professor Richard Sambrook.

For example, the “Conservatives rebranded their Twitter account to look like an independent fact checking account … [and] tried to ‘Google-jack’ the Labour Party’s manifesto launch with a fake news site.” They also doctored video to call a political opponent’s competence into question.

Other parties too — the Liberal Democrats and Labour — tried to misrepresent various facts to their advantages.

5. Fight bots, whatever their source

Regardless of where the information is coming from, remain on your guard against efforts to mislead you or confuse your thinking. Pik-Mai Hui and Christopher Torres-Lugo, computer science and information scholars at Indiana University’s Observatory on Social Media, offer some hope that people can protect themselves from misinformation and disinformation.

They and others in their research group have developed several different pieces of software that can help analyze automated propaganda efforts on Twitter. Lots of people have asked them to help identify Twitter bots acting in concert with each other.

“That is why, as a public service, we combined many of the capabilities and software tools our observatory has built into a free, unified software package, letting more people join our efforts to identify and combat manipulation and misinformation campaigns,” they write.

With a little computer know-how, you can spot new places where disinformation efforts are appearing — and steer yourself and others clear of their efforts to change your mind and steal your vote.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Jeff Inglis, Politics + Society Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.