A second HIV patient has been ‘cured,’ but researchers say reducing cases is still the top priority

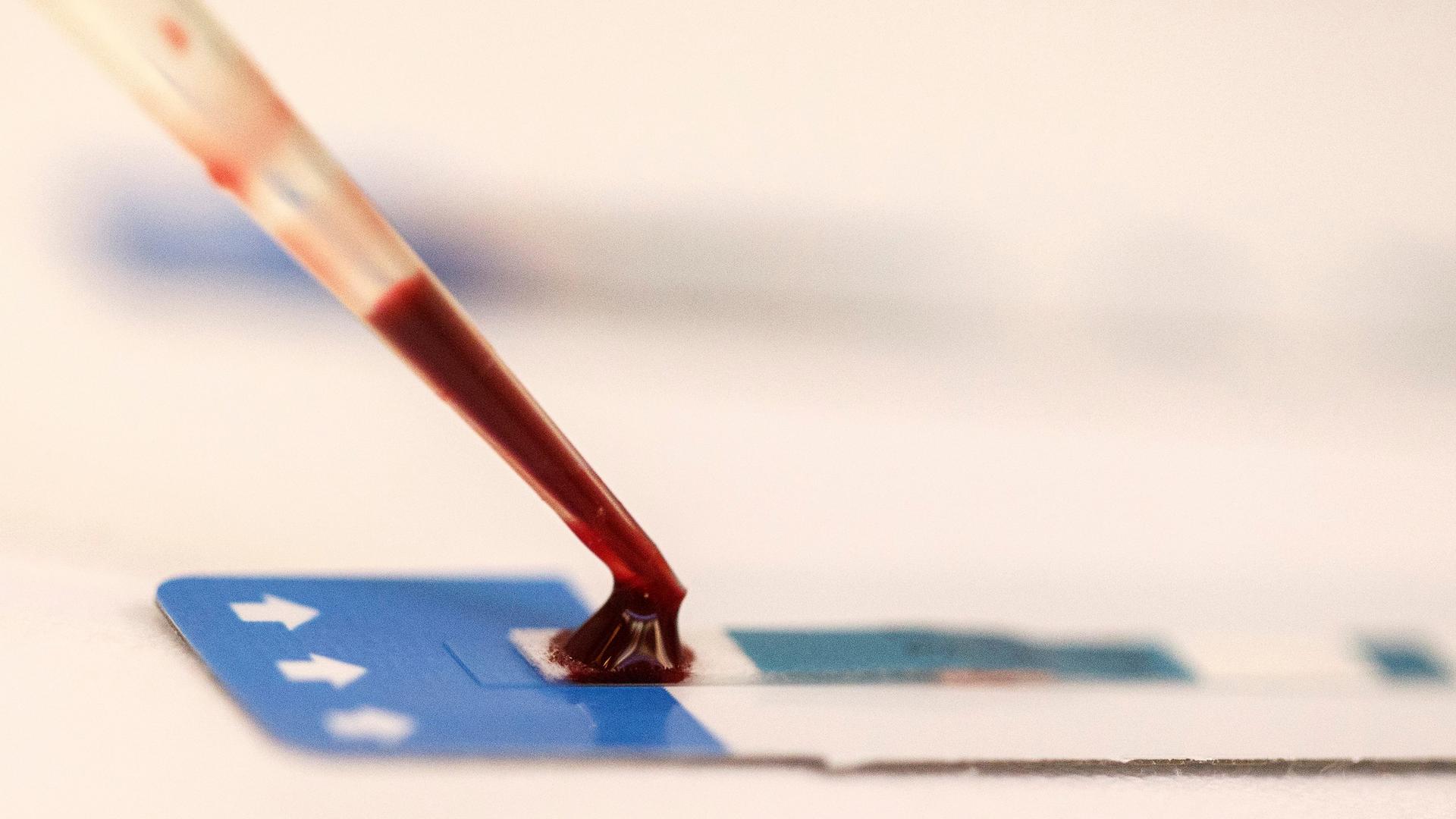

A nurse tests a blood sample during a free HIV test at a blood tests event in Bangkok Sept. 20, 2014.

The early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis were terrifying, especially for the gay community.

But today there may be some reason for excitement — what some are calling a “cure” for HIV.

A man referred to as the “London Patient” underwent aggressive, experimental treatment, and he’s been in remission for 19 months.

This is now the second time that scientists have been able to essentially cure a patient who has the virus.

The research is being presented at an HIV/AIDS conference in Seattle, Washington.

Sarah Fidler and Richard Hayes are two HIV researchers from London who they spoke to The World’s Marco Werman from Seattle about what the potential for a cure means to the 37 million people living with HIV and AIDS around the world.

Related: In South Africa, HIV rates are rising in young women and girls

Marco Werman: Why is it too early to call this a cure? this is no doubt exciting news right?

Sarah Fidler: It’s an interesting way forward in that it makes us believe that it is a possibility that HIV could be cured. But — this is my own personal feeling — there is a lot more important work to be done in the field rather than just exploring this one quite intensive and aggressive treatment. You know, we’ve got to look at the scale of the HIV epidemic. There’s nearly 40 million people in the world living with HIV and this is one man.

And Richard Hayes, how do you feel?

Richard Hayes: Well, like Sarah, I think this is interesting, well, exciting, I think I would say because it’s replicated what was seen was about 10 years ago when the Berlin patient was reported. So to have that finding replicated shows that it wasn’t just a one-off. But that’s a longer-term strategy and I think right now, we need to focus on bringing down the incidents of HIV globally.

Sarah, maybe you can just give us a little context on what a cure would look like in the West.

So there’s no doubt that a cure that could be more broadly applicable will involve antiretroviral therapy, which is what we have at the moment. But there may be additional tools that could either enhance the body’s own immune system to try and target these sort of residual cells, to get rid of them. And it may be that the patients who go through these sort of different strategies may not be officially cured — as in, you may be able to detect some virus still present. Which incidentally at the moment, is not the case with either the Berlin patient or this London case. So they are truly cured.

But there is another approach that may confirm what people are calling a remission — where we may be able to find virus in a blood test, but actually there’s no virus circulating around the body, which means that person’s immune system will function. And they, more importantly, are not also at risk of passing the virus onto their partners.

Richard, you and your colleagues have conducted research in Zambia and South Africa that stresses prevention and treatment. I mean, it’s not a cure but do you feel that it the reality of what needs to be focused on right now?

In theory, this is a very strong approach to bring down the number of new infections. What we’ve been doing is to test whether that can actually be delivered in practice, in these very challenging environments in southern Africa. And if it is possible, what effect does that actually have on the number of new HIV infections? The idea is that everyone in the whole community — and we’re talking about communities with severe HIV epidemics in Southern Africa …

And does that mean severe?

Well, it means that up to 20 percent or more of adults have HIV, which is obviously an extremely high rate. So one person in five. And a cure, to be honest, is going to be many years I think being developed. Meanwhile, we have this alternative approach: universal test and treat. The concept is to get them linked to the clinic where they are offered immediate antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Related: Why violence is linked to the rising rate of HIV in South Africa’s young women

What happened during the study what did you find?

Yes, so we worked in 21 communities. These were urban communities in Zambia and South Africa. And in two of those groups, we provided a very intensive communitywide intervention, where every house in the community was visited by our community health workers. They visited every household in the community to offer HIV testing and then they helped to link HIV positive individuals to the clinic and help them to get on to ART. And importantly, to stay on ART so that their virus will be suppressed. And you know, maybe I can ask Sarah to explain what we found in the trial and in terms of the results.

Sarah, can you explain that?

What we found at the end of the trial, which is what we are going to present tomorrow, is that the arms of the communities where they received our intervention we saw a significant reduction in the number of new infections when we compare those infections with our control communities. But I think our key message is that we need to do a lot more to support people knowing how … if we can do that, this is one very key way of reducing the number of new cases. And we think it’s really very relevant to many countries, particularly those countries living with high rates of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yes, so a reduction not a cure — and I don’t want to obsess about this word cure — but I mean is that combination intervention? Are you hopeful that can lead to essentially an elimination of HIV?

Hayes: I think it can work towards that. So remembering that there are nearly 2 million new infections a year. Even a 30 percent reduction on that would be several hundreds of thousands of people would be spared HIV infections. So we’re talking about enormous numbers here.

What is the reality though for patients on the ground? Because the treatment and prevention path looks ideal from the outside but there must be difficulties for patients that you’ve encountered.

Fidler: Testing for HIV and living openly with HIV is highly stigmatized still and just physically accessing care requires people often to take an entire morning or even a day off work. I mean, one of the things that we’re very keen to do is look at how scaleable this might be and of course whether it’s cost effective. Providing treatment for people living with HIV is a lifelong requirement and that sort of links together some of the things we’ve talked about but that’s why people are very interested in a cure for HIV because although because although the medicines for HIV are very very effective, we do need to take them every single day for the rest of your life. And if you’re a health care provider in a resource-limited setting where one in five of your population lives with HIV, that is an enormous burden in terms of provision of care as well as funding.

So what else do you want to see from cases like the London patient that will give you some more hope?

Fidler: I also work as a clinician in the UK. And the London patient is a very interesting — and as Richard says, it’s exciting and it’s inspiring — that this might happen, that it is actually possible to cure HIV. However, I think what we have learned from this case is we can understand a bit more detail about what it would require to make this into a more scalable approach. But I think we can learn from what we’ve seen in terms of the science of these kinds of approaches. That something that’s less dramatic may well allow us to keep people well off antiretroviral therapy longer term.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.