Earth’s hottest decade on record marked by extreme storms, deadly wildfires

A woman collects belongings from her damaged home in the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian on the island town of Marsh Harbour, Bahamas, on Sept. 3, 2019.

Deadly heat waves, wildfires and widespread flooding punctuated a decade of climate extremes that, by many scientific accounts, show global warming kicking into overdrive.

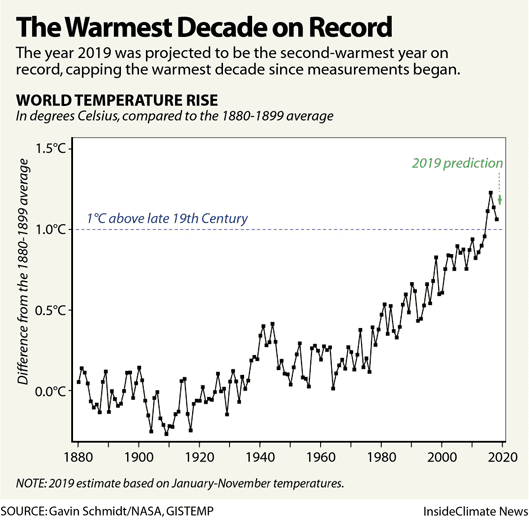

As the year draws to a close, scientists are confidently saying 2019 was Earth’s second-warmest recorded year on record, capping the warmest decade. Eight of the 10 warmest years since measurements began occurred this decade, and the other two were only a few years earlier.

Arctic sea ice melted faster and took longer to form again in the fall. Big swaths of ocean remained record-warm nearly all year, in some regions spawning horrifically damaging tropical storms that surprised experts with their rapid intensification. Densely populated parts of Europe shattered temperature records amid heat waves blamed for hundreds of deaths, and a huge section of the US breadbasket region was swamped for months by floodwater.

And wildfires burned around the globe, starting unusually early in unexpected places like the UK. They blazed across country-size tracts of Siberia, fueled by record heat, flared up in the Arctic and devastated parts of California. Australia ended the decade with thick smoke and flames menacing Sydney and a record-breaking heat wave that sent the continent’s average temperature over 107 degrees Fahrenheit. Again and again, scientists completed near real-time attribution studies showing how global warming is making extremes — including wildfires — more likely.

Even more worrisome, scientists warned late in the year that many of these extremes are linked and intensify each other, pushing the global climate system ever-closer to tipping points that could lead to the breakdown of ecological systems — already seen in coral reefs and some forests — and potentially trigger runaway warming.

“Every decade or half-decade we go into a new realm of temperature. When you look at the decadal averages, it becomes pretty obvious that the climate of the 20th Century is gone. We’re in a new neighborhood,” said Deke Arndt, chief of the Climate Monitoring Branch at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

“When I look at the patterns, the thing that always comes back to me is, we share one atmosphere, one climate system with people we will never meet. When we poke it here in our part of the world it can have mammoth consequences elsewhere,” he said.

The record heat and weather extremes are affecting millions of people worldwide, said Omar Baddour, who helped compile a World Meteorological Organization report showing that more than 10 million people were displaced by climate extremes in just the first half of 2019. In addition to extreme weather, warming can increase the risk of mosquito-borne diseases like malaria, rising sea levels and erosion can make coastal areas uninhabitable, and increasing heat can harm agriculture and water supplies communities rely on.

“It’s really serious. We are getting into a self-sustained loop of global warming that could lead to 3 to 5 degrees Celsius (5.4 to 9°F) of warming by the end of the century,” he said. “We have been recording 2,000 to 3,000 excess deaths from heat waves. This is really becoming a disaster. Humans are suffering.”

Globe-spanning heat waves

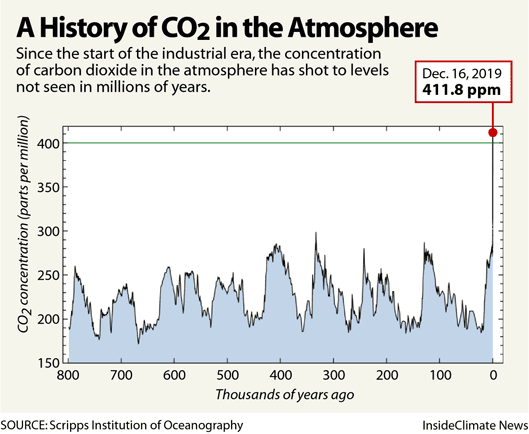

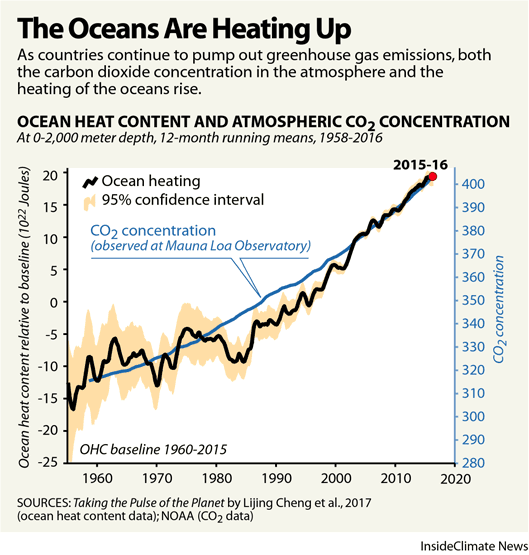

It was clear long before the decade started that human activities were driving global warming. The inexorable heat-trapping effect of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases is heating Earth dangerously, and there is no slowdown in sight. Record CO2 emissions were reported again this year, due largely to the burning of long-buried carbon, in the form of coal, oil and gas.

That CO2 can linger in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. Before the industrial era, the atmospheric CO2 concentration was around 280 parts per million. In 2010, it passed 390 ppm. This year, it reached 415 ppm at its seasonal peak, a level not seen on Earth since at least 3 million years ago, when global temperatures were 3 to 4 degrees Celsius warmer than now, sea level was 65 feet higher and evidence suggests beech trees grew near the South Pole.

Perhaps nothing points more clearly at the link between greenhouse gases and global warming than the surge in heat waves during the past decade, starting in 2010, when North America, Europe and Asia all experienced extreme record-high temperatures at the same time.

In its 2010 global State of the Climate report, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration described the event as a global heat wave lasting from June through October, with record high temperatures spanning the Northern Hemisphere. In June of that year, well-above normal temperatures spanned the globe.

The US was hit by extreme heat waves the next two summers, and a year later, Australia experienced what became known as the “Angry Summer,” with a seven-day span when the country’s average temperature each day exceeded 102°F.

The 2013 heat wave in Australia was one of the first, but not the last, to be linked directly with global warming. By 2017, when the Lucifer heat wave blazed across Southern Europe, scientists said it was made 10 times more likely by global warming. By the end of the decade, climate attribution studies showed that extreme heat events in 2018 and 2019 wouldn’t have been possible without global warming.

Research during the 2010s also showed the links between heat waves and droughts, like the dry spell that gripped California for five years, as long spells of above-average temperature lead to massive evaporation of moisture from soils and plants.

‘Like the world was on fire’

Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann singled out fire as a gut-wrenching manifestation of the changing climate.

“It literally felt like the world was on fire,” he said. “The unprecedented extreme weather events we saw once again that were undoubtedly fueled by human-caused planetary warming. The year 2019 really drove that home.”

“My alma mater (UC Berkeley) was closed down due to the California wildfires at the same time the location of my upcoming sabbatical (Sydney, Australia) was blanketed in smoke from simultaneous brush fires. Australia and California aren’t supposed to have simultaneous fire seasons. But now they do,” he said.

Global warming dries out forests, making them more flammable and enabling flames to spread faster. Warmer nighttime temperatures in recent decades also mean that fires don’t die down after the sun sets, and warmer temperatures contribute to fire conditions lasting longer.

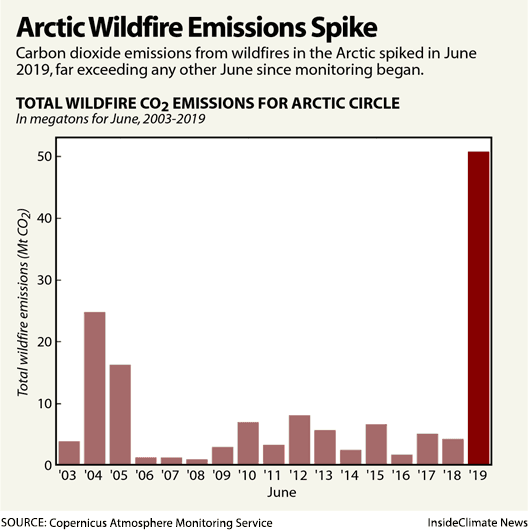

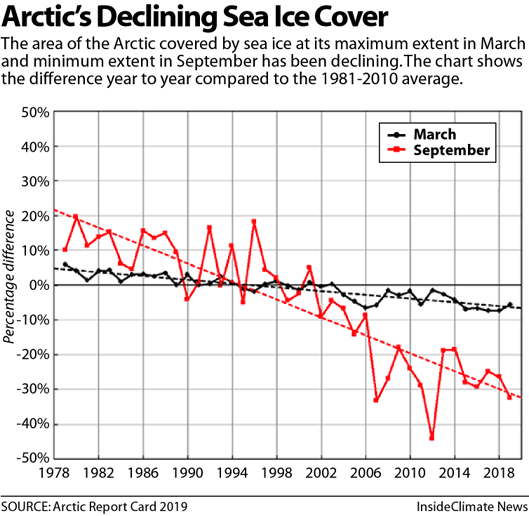

Wildfires are normally rare in the frozen realms of the Arctic, but the relentless retreat of reflective sea ice cover has enabled the sun to warm the Arctic Ocean and adjacent land areas. That dries the vegetation, making it susceptible to ignition, and the warmer atmosphere is triggering more storms with fire-igniting lightning strikes in the region.

As a result, CO2 and other emissions from Arctic wildfires were above average for several weeks in a row in 2019, said Mark Parrington, who tracks the fires for the European Union’s Copernicus Earth Observation Programme.

“The most unusual, and unexpected, fires in 2019 were poleward of the Arctic Circle,” he said.

The decade started with unprecedented wildfires in Siberia from July through September, fueled by a heat wave that climate researchers at the time called a black swan event, “well beyond the normal expectations in the instrumental record.”

The years since have brought more record blazes and devastation, including California’s deadliest wildfire season, in 2018.

This year, Europe saw its worst wildfire season on record. California was once again scorched during what should have been the start of the rainy season, and large parts of Australia were wracked by weeks of wildfires in November and December during a very early start to the fire season as temperatures again broke national records. Wildfire activity also surged unusually far north in Alaska, as climate researchers again warned that there is no reason to think the trend toward bigger and more destructive fires will change any time soon.

Intensifying hurricanes and record rainfall

On the other end of the climate spectrum from fire is extreme rainfall and flooding, and there was plenty of that in 2019, which was on track to be the United States’ wettest year on record, said NOAA’s Arndt.

“I think this year is an exclamation point of what we’ve seen a lot this decade. We’re having big rainfall storms, whether they are tropical or stuck weather systems,” he said.

Increasingly, scientists are linking extreme rainfall from tropical storms with global warming, including this year’s Hurricane Dorian, which picked up more moisture in the human-warmed atmosphere and pounded the Bahamas for nearly three days, stuck in a stagnant weather pattern that may have been caused by global warming, scientists said.

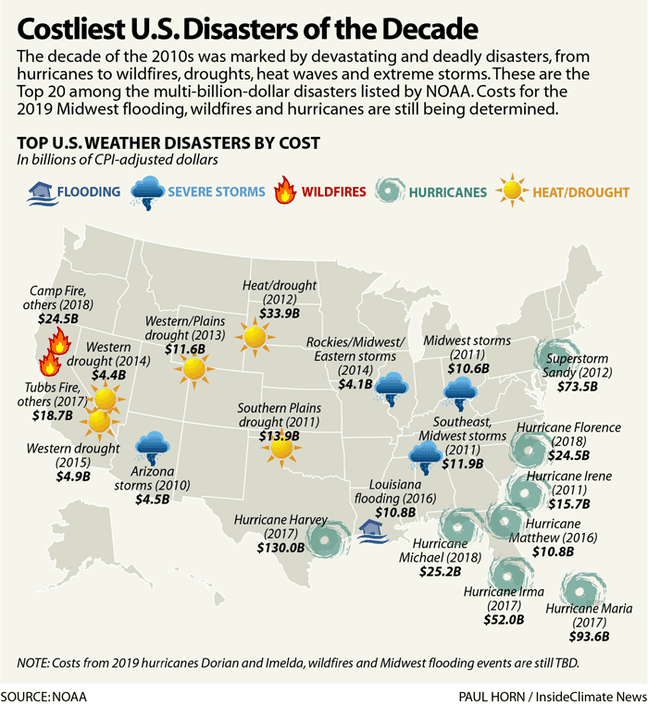

Hurricanes draw energy from warm ocean water, as Florida saw in 2018 when Hurricane Michael exploded in strength before hitting the town of Mexico Beach with 160 mile-per-hour winds. The hyperactive 2017 Atlantic hurricane season had been the most destructive on record with Hurricane Harvey, which flooded Houston with days of record rainfall, and Category 5 storms Irma and then Maria, which devastated Dominica, the US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

The links between inland flooding and global warming are also becoming increasingly clear, with several studies this past decade showing how a warmer atmosphere can bring more extreme rainfall and even change flood patterns. The Midwest saw what that can mean in 2019, when the region’s wettest January-to-May period on record brought record high water that devastated farms in several states.

Scientists said they also expect intensifying atmospheric rivers to increase flood risks during the West’s winter rainy season, while warming spring temperatures are raising the danger of rain-on-snow floods.

The big melt in Greenland and Antarctica

Earth’s icy realms are especially sensitive to global warming, and they’re adding to sea level rise that puts coastal areas around the world at risk.

“It’s a disaster in slow motion,” said climate scientist Jason Box, who focuses on the Greenland Ice Sheet. “We’re hearing a coherent signal across the board. The whole hydrological system across the Arctic getting hyperactive. There’s more rain, more snow, more melting, higher humidity and lower sea ice. But we’re not internalizing this enough,” he said.

“Is it denial? I don’t know. Is the human frog in the pot analogy? There’s an argument that humans have not evolved to deal with the long-term threats,” he said, adding that the human response to global warming seems to support that thesis.

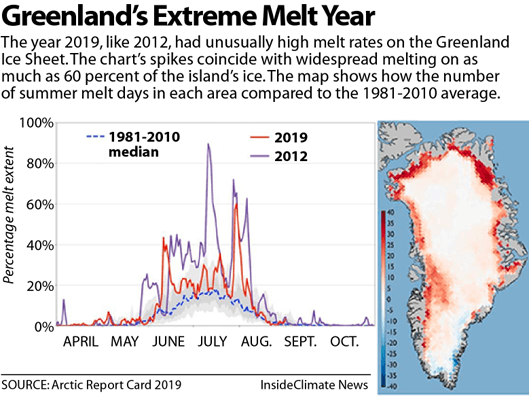

In 2019, Greenland saw widespread melting. It began with a very early start of the melt season followed by record warm air later in summer.

The rate and magnitude of Greenland Ice Sheet mass loss, and of ice loss globally, has been dramatic, said Twila Moon, a climate researcher with the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Various feedback cycles that hasten melting have become more visible, she said, “for example, when winter snow has melted around the Greenland edge, it reveals darker glacier ice. That darker ice more easily absorbs energy and more melt is created.”

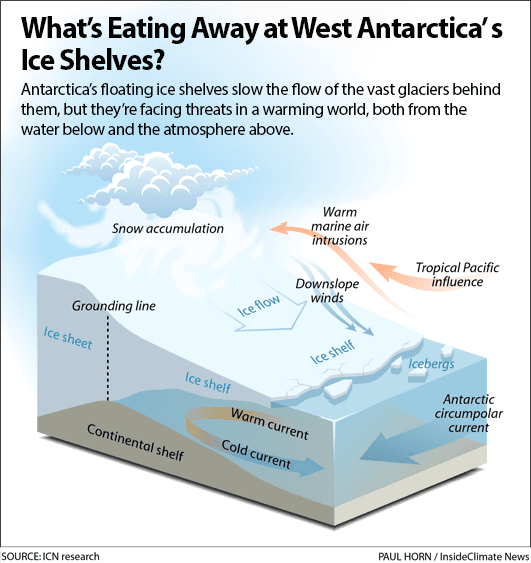

“It was only a couple of decades ago that we were realizing we needed to pay attention to the big ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica on shorter timescales,” she said. “This decade also brought a richer understanding of how the ice sheets interact with the ocean. Warm water at depth is very destructive for ice sheets.”

Warming oceans, in combination with shifting currents and winds, have started melting West Antarctica’s ice shelves from below, which can speed the flow of the land ice behind them to the sea and accelerate sea level rise. If just the West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to melt, it would raise global sea level by more than 10 feet, and there is now strong evidence that human-caused warming is accelerating that process, said ice sheet researcher Mike MacFerrin.

Antarctic sea ice, which hit a record low in 2019, has also been an interesting story, said Walt Meier, a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

For the first part of the decade, Antarctic sea ice expanded, “contrary to what one expects in a warming environment, he said. “However, in 2016, things completely reversed and by 2017 there was a record low minimum and a record low maximum extent, and 2018 followed with the second lowest minimum and fourth lowest maximum.”

“What happens in the future is hard to say, but with continued warming, the trends in sea ice will start to turn negative,” he said.

The last decade is also notable for Arctic heat waves and repeated low Arctic sea ice levels, Meier said. The past 13 years had the lowest Arctic sea ice extent in the satellite record.

Global warming took a big bite out of the world’s mountain glaciers in 2019, as well, with extreme melting especially evident in the European Alps, where scientists are closely tracking the retreat. Even after heavy winter snows, Swiss glaciers once again lost a record amount of ice.

“The biggest thing that emerged looking back over the last decade is the number of extreme years that seems to go completely beyond natural variability,” said Swiss glaciologist Matthias Huss. Nearly every year of the decade into the extreme melt category. Even massive, sometimes record-setting winter snowfall, can’t offset the melting from summer heat, he said.

In the Swiss Alps, about 20 percent of the total ice volume has been lost since 2010, reflecting a trend across the entire Alps. A study published this year showed if the current greenhouse gas emissions trajectory continues, more than 90 percent of the Alpine ice will be gone by the end of the century, affecting water supplies and power production as it disappears.

Tying it back to global warming

The 2010s were the decade that attribution science, which analyzes the connections between global warming and extreme events, came of age, particularly through the work of the World Weather Attribution program.

The program’s international team of scientists looked at a wide range of extreme events in the last few years. Every time they analyzed a heat wave, they found global warming fingerprints.

They found that the then-record setting global heat of 2014 was made 35 to 80 times more likely by global warming. In another study, they found that if global greenhouse gas emissions aren’t capped, heat waves like 2017’s “Lucifer” in the Mediterranean region will be the new normal by the middle of the century, and that the summer of 2019’s extreme temperatures in France would have been nearly impossible without global warming.

This story was originally published by InsideClimate News.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?