For centuries, migrants have been said to pose public health risks. They don’t.

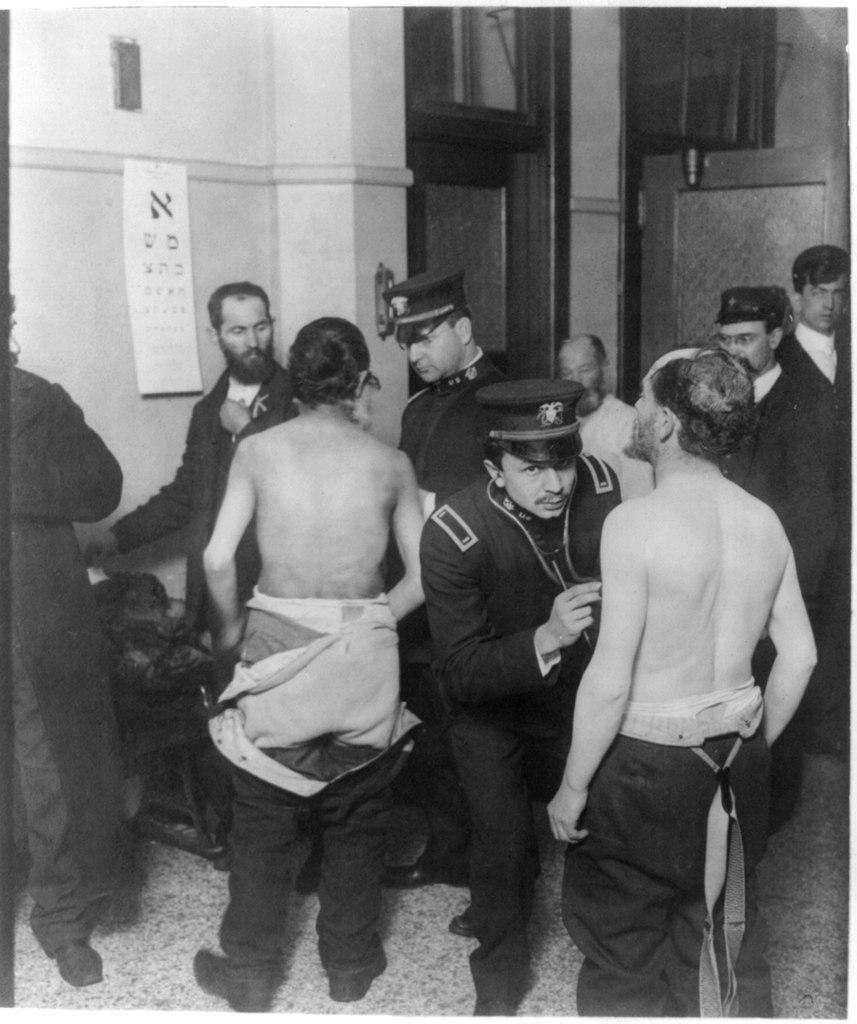

Immigrants undergoing medical examination at Ellis Island, New York, between 1902 and 1913.

The trope that migrants bring diseases that threaten immigrant-receiving countries is among the most pervasive myths touted in anti-immigrant discourse, and one justification of racist and humiliating policies directed toward immigrants throughout history.

Though there are some historical examples — such as the spread of disease from European colonizers — decades of research have debunked the idea that modern immigrants writ large pose an extreme health risk. But the rhetoric remains prevalent. Fox News commentators, such as Laura Ingraham and Marc Siegel, described immigration as a source of disease and national security risk, pointing to outbreaks of illness in immigrant detention facilities.

Related: Long before anxiety about Muslims, Americans feared the ‘yellow peril’ of Chinese immigration

“You’re absolutely right calling this a public health emergency. That’s part of the problem here. It’s a big part of the problem. And it ties in with national security. Multiple diseases are coming in with the migrants,” Siegel, a physician, said in a March interview with Ingraham.

But while the conditions of migration — including difficult transit routes, inadequate access to services and arrest and detention — can contribute to a risk of ill health for migrants themselves, according to a study from The Lancet, “the risk of transmission from migrating populations to host populations is generally low. … Additionally, migrants are, on average, healthier, better educated and employed at higher rates than individuals in destination locations.”

Erika Lee is a professor of immigration history at the University of Minnesota. Her forthcoming book is called “America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States.” Lee spoke with The World’s Marco Werman about the prominence of disease rhetoric in America’s history of anti-immigration stances.

“… whatever “immigrant menace” was the focus of xenophobes in the past … the claim has always been that these groups were not only racially inferior, but that they brought particularly dangerous and contagious diseases.”

Lee: It’s absolutely been a driving factor throughout the centuries. We know that whatever “immigrant menace” was the focus of xenophobes in the past — whether it be Irish Catholics in the 19th century, then later Chinese and other Asians, of course, Italians and Jews and other southern and eastern Europeans and Mexicans — the claim has always been that these groups were not only racially inferior, but that they brought particularly dangerous and contagious diseases that would end up harming the US native population.

Marco Werman: Did all this start at the time of the Irish potato famine in the 1840s?

Actually, it goes back even further. One of the first public health inspection buildings was set up in Philadelphia to process German immigrants during the colonial era. But of course in the 19th century with Irish Catholics coming in such great numbers — also they were amongst the most impoverished and also very ill from the potato famine in Ireland — they became the source of a great debate over their public health.

And not just germs, right? I mean, we often hear criticism of immigrants’ knowledge of sanitation.

Absolutely, it was one of the arguments that many people made in terms of how [immigrants] were not fit to be citizens: That they simply did not know how to live in sanitary conditions, that they themselves had come from uncivilized backgrounds, savage backgrounds, and that part of the process of becoming American, of assimilating them, was to really teach them from the ground up how to properly clean, how to cook and how to keep a sanitary household.

But travelers can spread disease. I think of Europeans bringing smallpox and other pathogens to the Americas at the beginning of the colonial era or yellow fever outbreaks in the South in the 1800s. Intellectually, do you understand the fear?

“… what makes xenophobia even more powerful is that it then gets applied to an entire group and it becomes racialized …”

Absolutely. Of course, there is an important need for us to identify individuals who are bringing contagious diseases. I think what changed — and what makes xenophobia even more powerful — is that it then gets applied to an entire group and it becomes racialized as something that’s endemic to an entire population, rather than individuals who should be screened and then taken care of.

I know you’ve kind of done a lot of research on your own family history. Have any of these issues around disease ever kind of come up as you’ve gone back through the years?

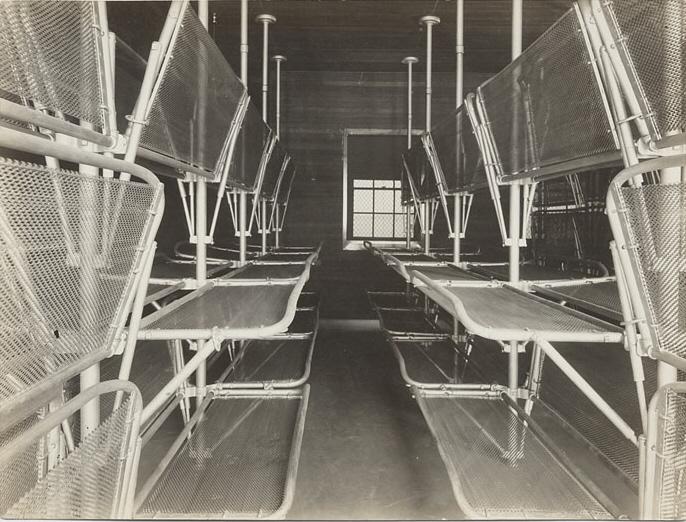

Yeah, absolutely. My grandfather came to the United States in 1917 through San Francisco and was detained on Angel Island for two weeks. And one of the first things that he and all other arriving Chinese were faced with was an extremely humiliating and particularly invasive medical exam. So, immigration doctors were tasked with not only screening immigrants for contagious diseases, but also for parasitic diseases — things that were easily treated with antibiotics, but were used as a cause or a reason for exclusion.

“… medical examiners also stripped Chinese naked and performed all sorts of measurements and detailed examinations on genitals and teeth and various different other body parts … the Chinese knew that no other group at Angel Island — including Europeans or Japanese or Mexicans — were being subjected to these kinds of examinations.”

But on top of that, the medical examiners also stripped Chinese naked and performed all sorts of measurements and detailed examinations on genitals and teeth and various different other body parts to determine their age. This was in some part due to the expectation or the belief that Chinese were coming in fraudulently and were using false identities to enter the United States, but they also were used or were interpreted [and] experienced by Chinese immigrants as one more example of a highly discriminatory regime. Because the Chinese knew that no other group at Angel Island — including Europeans or Japanese or Mexicans — were being subjected to these kinds of examinations.

Was your grandfather admitted to the US ultimately?

He was. After two weeks, he was.

But, no doubt, never forgot that experience.

No, he didn’t. Another example: The idea that Mexicans were particularly dirty and diseased were some of the main arguments stoking xenophobia in the early 20th century. [Mexican immigrants] were regularly charged with being responsible for typhus and plague and smallpox along the border and to be infested with vermin. So when they crossed the border, US Public Health Service officials inflicted disinfecting baths on them to remove lice, but also just sprayed them. You see pictures from this period of groups of Mexican men being almost, you know, sprayed like cattle for the alleged diseases that they were bringing in.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.