For many, international adoption isn’t just a new family. It’s the loss of another life.

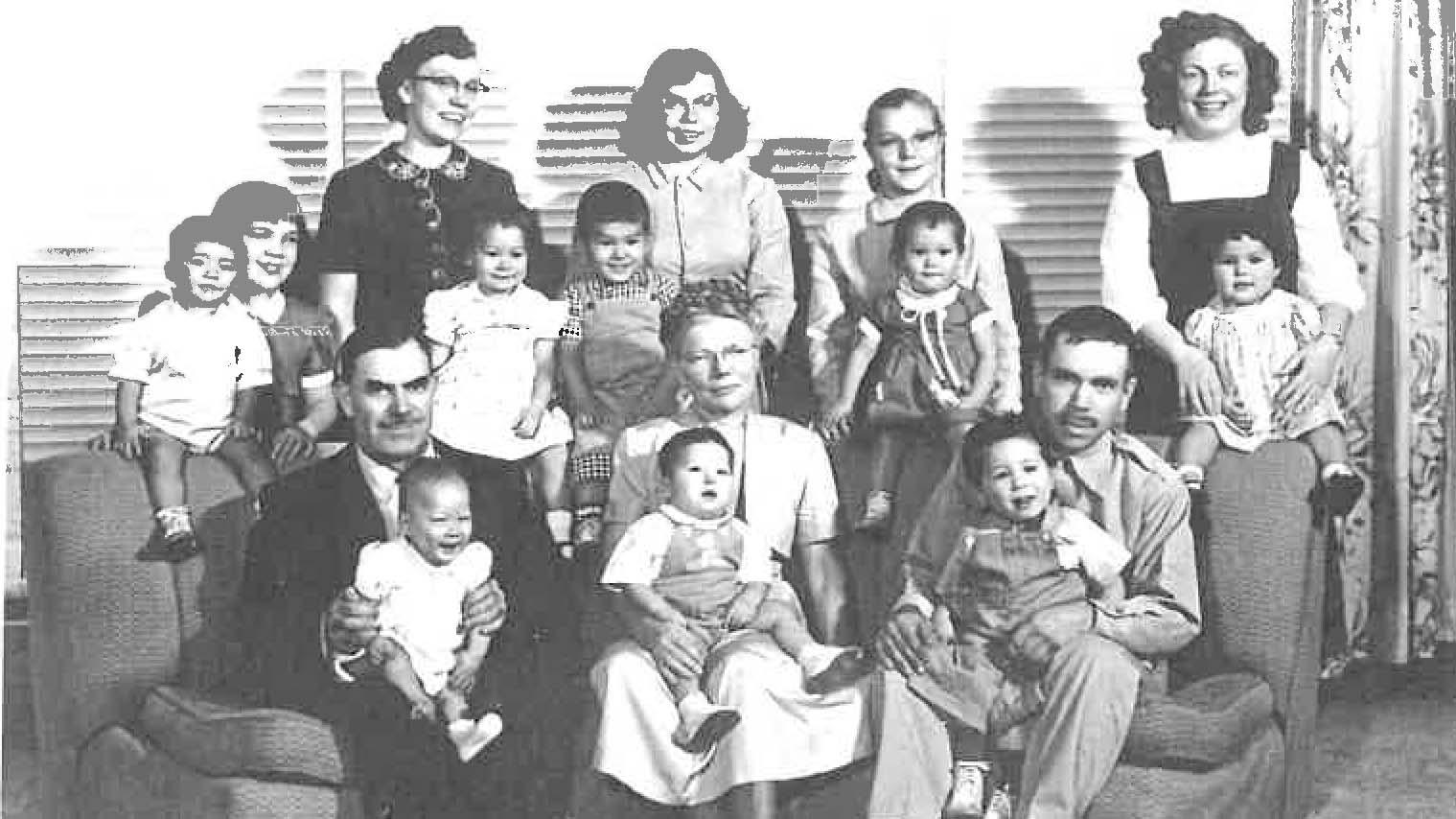

The Holt family around 1955 or 1956. Harry Holt was an Oregon farmer who adopted eight “Amerasian” children after hearing about their dire situations post-Korean War. He went on to adopt thousands of other children as a “proxy agent” for desiring American couples.

In 1978 I was adopted from South Korea by a white, Christian couple in the United States. Like me, thousands of Korean children have been sent to homes all over the world since the end of the Korean War. In 2010, when I traveled back to South Korea for the first time since my adoption, I realized that the “motherland” I know in the United States — the one that “rescued” me 40 years ago — has actually stripped me of my own heritage.

Related: 30 years later, this Korean adoptee finds ‘home’ again

This isn’t unique to me. The US has used children to advance dominant racial, religious and political ideals at the expense of the oppressed and the poor for a long time. And it continues today. The heartwrenching family separation policy at the border that made headlines last year is just one example that has put children at risk for ending up in foster care or adoption, rather than reunification with their families.

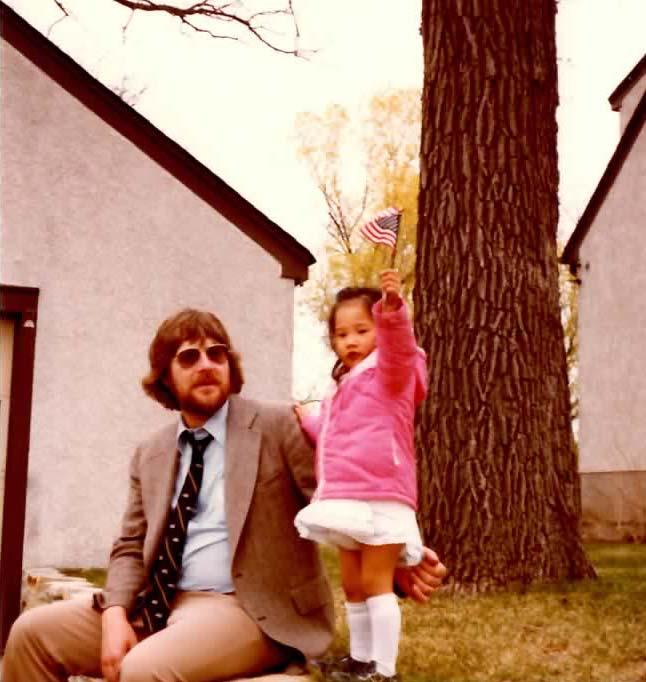

Here is what I know: I am culturally American. I am racially Asian. I identify as a Korean adoptee. And while my ethnicity is Korean, I grapple with how Korean I actually feel. I came to the US when I was just over six months old, and a couple years later I was naturalized as an American citizen. I have no physical memory of this, only a faded and tattered photograph of me waving the American flag outside my house on the day of my naturalization ceremony.

While my identity has always been a complex personal journey, I became interested in the history of Korean adoption as a doctoral student. I fell in love with archival research and being transported back in time through historical documents. My personal and professional identities came together, and I wanted to know more about my own history as a Korean adoptee.

As I dug through boxes and boxes of documents, many of them letters written back and forth between social service agency workers in the US and Korea during the 1950s, I started to think about the idea of “national motherhood.”

As for most people, to me, a “mother” was an individual. The word would generate images of my own adoptive mother. Memories of her would pop into my head — I would see her face, hear her voice. She didn’t give birth to me, but she raised me from infancy. She is still my mom some 40 years later.

But the idea of motherhood is also a political ideology. During the Cold War and subsequent Korean War in the early 1950s, the US “mothered” South Korea out of the grips of the communist North and brought it into the modern world. It also replaced Korea as motherland to over 200,000 Korean children through institutionalized adoption.

The Korean War left the South in ruin. Among the suffering were tens of thousands of widowed Korean women and orphaned and abandoned children, many of them biracial — offspring of Korean women and foreign servicemen. Given the devastation after the war, many of these children — especially biracial children, termed “mixed blood” — had little to no chance at survival in Korea, and expeditious emergency rescue efforts were carried out to save these children.

During the 1950s, many Americans saw Korean adoption as a civic duty to ward off the spread of communism in the US and abroad. Bringing Asian children into white Christian families was also part of an anti-racist image, showcased in new mixed families. But the practice also removed children from their culture, adopting them into white, middle-class America, where many lost touch with the cultural heritage of their birthplace.

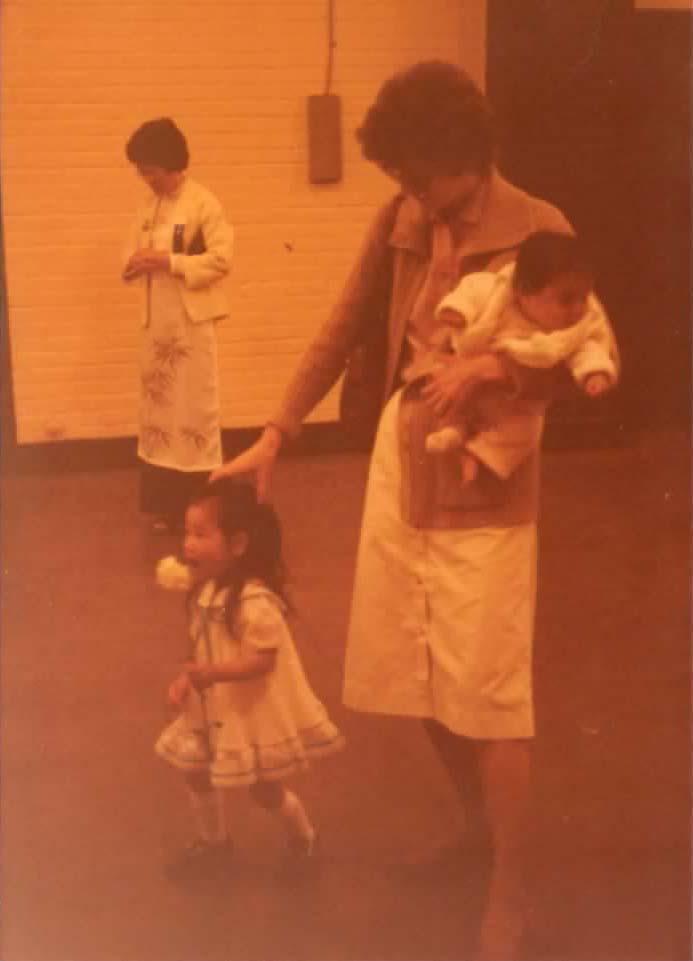

I never realized the widespread effect of this broader history of Korean adoption until I had the chance to travel back to South Korea for the first time since I was adopted. In August 2010 I returned to the country of my birth for the first time since being adopted as an infant. While I was there I visited the orphanage I stayed in until I was adopted to the United States. This was a life-changing experience, and it was the catalyst for my life’s work as a college professor and critical adoption scholar.

Read Shawyn’s ‘homecoming’ story

Nearly nine years have passed since my homecoming trip to South Korea. During that time I have continually wrestled with the fact that my ethnic and cultural heritage was stolen from me. I came to the United States and was assimilated into American culture, values and identity. I became white in every way with the exception of my skin color. I never had my own language. Instead, the “mother” tongue I developed was one filled with the colonial words of a Western nation that exported hundreds of thousands of children for its own financial and political gain.

Behind the altruistic and benevolent values that motivated many child-removal schemes in American history are ulterior motives bound up in financial gain, religion and nation-building. Generations of young people have been, and continue to be, assimilated to the dominant culture. During the late 19th and early 20th century, thousands of Indigenous children were removed from their families, cultures and lands and sent to boarding schools to “kill the Indian. Save the man.” Around the same time, the orphan train movement took thousands of immigrant children from the eastern United States and sent them to white Protestant families in the midwest to instill them with Christian values and an American work ethic. These are just a few examples. Families and communities all over the world mourn the loss of their children. And worse, these families and the children taken from them often endure lifelong trauma.

The profession of social work institutionalized international adoption in the mid-1950s. It laid the groundwork for procedures still used today. These procedures include in-depth screenings of prospective adoptive families; coordinating the matching and placement processes; the ongoing communication and visits between social service professionals and the adoptive family from the initial placement to the final adoption; and follow-up services and resources.

These processes are meant to ensure a child is placed with a healthy, capable family, and will thrive in a new environment. But for a long time, conversations about retaining culture, racial issues and other challenges were not a part of these adoption processes. Today, many social service agencies now talk to families about these issues, offer trainings on racial and cultural identity and panels of adult adoptees share their own experiences.

These are vast improvements, but understanding the larger, much more complicated historical narrative of Korean adoption is still missing.

Adoption is a multi-billion dollar industry. What does it mean for the profession to be brokering monetary exchanges for human beings? Does the profession understand enough about historical and generational trauma to effectively address the effects of child removal? Understanding trauma is now starting to guide social work, but there still isn’t much work being done to apply historical and generational trauma to international adoptees.

Now, as a college professor helping to educate and train future social workers, I lean on my own history in my work. I have a complicated relationship with adoption. I understand very well why it is an important option for people. And if the choice is that a child will likely suffer or die, or have a chance at life in an adopted home, I will always hope for the child to thrive, wherever that may be.

My own adoptive mother has continually been interested in and supportive of my work. We have had many conversations as I continued to unpack my own adoption history, and the broader history I share with other Korean adoptees and international adoptees. I don’t hold any negative feelings toward her. And, generally speaking, I can’t hold any negative feelings toward anyone who wants to adopt or has adopted. I don’t know their situation or story.

But what I have come to learn is that adoption has a very complicated history. Without a full understanding of this history and the possible consequences, much damage has and continues to be done. As much as people think about the ways in which they are helping a child in need by “saving” them, they must also seriously question the ways in which they may be harming the child, a family, a community, and a culture.

One thing is certain: Once stolen, a person can never truly recover their cultural and ethnic heritage. How could anyone ever truly reconcile those losses?

Editor’s note: Shawyn Lee is an assistant professor in the Department of Social Work at the University of Minnesota – Duluth. As a critical adoption scholar, Shawyn’s work incorporates archival research, critical pedagogy and intersectional identity politics based on Shawyn’s personal experiences as a queer Korean adoptee. Read Shawyn’s story about going back to South Korea for the first time.

Disclaimer regarding ISS-USA historical records: Points of view in this presentation and/or document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of International Social Service, United States of America Branch, Inc. (ISS-USA).

The historical records of the International Social Service, United States of America Branch, Inc. (ISS-USA, located in Baltimore, MD) on which this study is based are held by the Social Welfare History Archives at the University of Minnesota (SWHA, in Minneapolis, MN). Permission for their use in this research project was granted by ISS-USA. For more information, see http://www.iss-usa.org and http://special.lib.umn.edu/swha.