Love conquers caste for this couple, but Indian marriage traditions continue in US

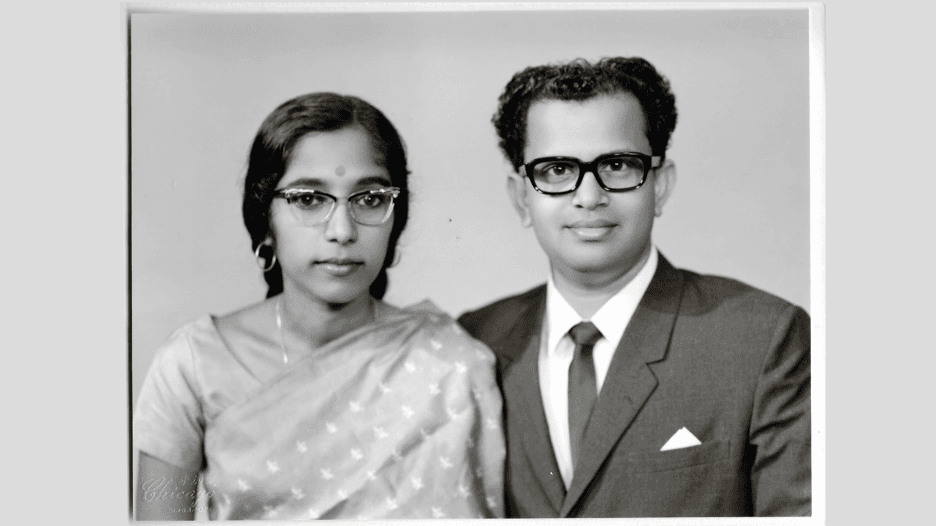

Studio photo of Indira and Bala Pillay. The Pillays lived in Singapore for a year before deciding to immigrate to the US.

This article is part two of the “Caste in America” series. Read part one and part three. This series was produced with funding from the Pulitzer Center and in partnership with WGBH.

For years, my mom, Indira Pillay, told her American friends and colleagues that she and my dad had had a shotgun wedding. Until one day, someone informed her that a shotgun wedding takes place when the bride is pregnant.

“We hardly touched each other before we got married,” she explains. “I thought it meant any no-frills wedding ceremony.”

Though my mom was not a pregnant bride, my parents’ simple and hurried wedding was cause for gossip and some scandal for one reason: They had fallen in love across caste lines.

“It was not scandalous,” says my dad, Bala Pillay. “It was not common. It was rare.”

“That is why it was scandalous,” says mom. “Anything which was rare was scandalous.”

My dad is a Nair, which is a dominant, upper caste. Nairs consider themselves to be the descendants of warriors, landowners and, in some cases, royalty. My mom, on the other hand, is from a lower caste called the Ezhavas. They were traditionally low-level agricultural workers who did jobs that were considered “unclean” by upper caste Hindus, such as tapping sap from palm trees to make wine.

As one of my parents’ friends put it: “Bala is from the lowest of the high castes, and Indira is from the highest of the low.” Yet, once upon a time, the social chasm between these two groups was so vast that it was unthinkable for even the shadow of someone from my mom’s caste to fall on someone of my dad’s caste.

My dad’s parents accused my mom of having performed black magic on their son to make him fall for her. Moreover, they said, nobody would marry the children of an inter-caste marriage.

“I told [my parents], listen, I don’t care about what all these relatives are talking about,” my dad recalls. “I love her, I want to marry her. If you don’t like it, you can go to hell.”

To my American ears, it sounds brave and romantic. To my grandparents, it was unimaginable.

My favorite aunt even claims that there were relatives who threatened to kill themselves and kill my parents for this “love marriage,” transgressing the Indian tradition of unions arranged by parents. My mom maintains that my aunt is exaggerating, though from what I can surmise, it probably is not much of a stretch. The more I learn about the obstacles my parents and other inter-caste couples have faced, the more I think that it’s comparable to what a black woman and a white man might have encountered had they planned to get married in the American South just after Jim Crow.

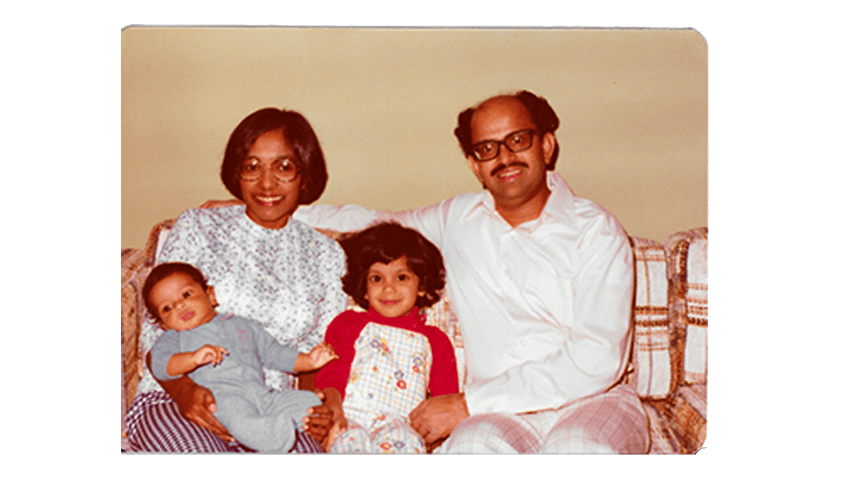

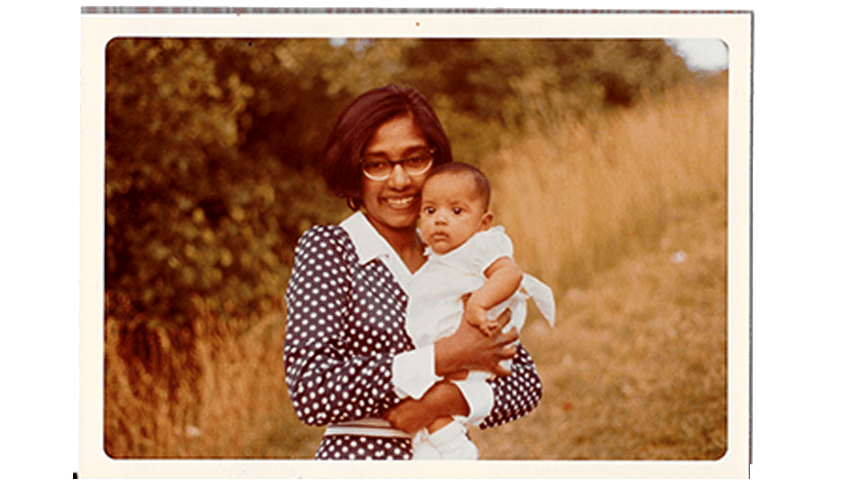

My parents’ marriage was possible because they met in medical school. They were both doctors, they saw each other as equals, and they had the financial wherewithal to leave India. In 1970 — five years after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act loosened restrictions on immigrants from non-European countries — my mom and dad arrived in Cleveland to escape their feuding families and begin their medical residencies.

In doing so, they entered the complicated caste system of America. We became what I would call “economic Brahmins,” but we inhabited murky racial terrain. Growing up in the hyper-segregated suburbs of Cleveland, I was asked “What are you?” more times than I can count. We were called the n-word more often than I care to remember.

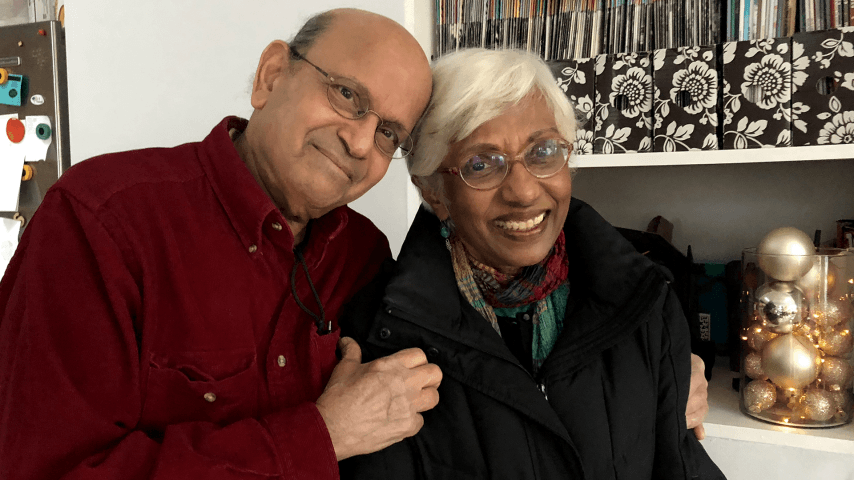

Today, my parents live in Hingham, Massachusetts, where they are busy enjoying the spoils of retirement. This includes spending winters in the south Indian state of Kerala, which is where our family is originally from. Kerala has become a tourist hotspot in recent years and has India’s highest literacy and life expectancy rates. Compared with the rest of India, the state is known for being highly progressive.

Yet while inter-caste marriages have become more common than they were in 1969, they are still far from the norm in Kerala, let alone in the rest of India. More people migrated out of India than any other country in 2017, according to a United Nations report. For this growing diaspora, the option to marry someone of the same caste has been made easier by an array of matrimonial websites that list potential brides and grooms, specifying their caste and desire for a spouse from the same one.

I was born and brought up in America, and my Indian American friends and I never discuss caste. Probably because the vast majority of Indian Americans are like my dad, and come from India’s upper and dominant castes, as research by the University of Pennsylvania has found. Though we are all well-versed in the stories of how our mothers and fathers came here with one suitcase and a handful of dollars in their pocket, we have little understanding of how generations of caste privilege in India helped pave the way for our parents, us and our children to do well in this country.

My woeful — and at times, willful — ignorance about caste is especially egregious because I have spent extended periods of time in India as a reporter, producer and researcher. In 2006, while living in India on a Fulbright grant, I read an article in an Indian newspaper mentioning that Ezhavas were designated as an OBC — Other Backward Class.

“What the [expletive] is a backward class?” I thought. I found it impossible to reconcile the dignity, humor, generosity, intelligence and middle-class circumstances of my mom’s side of the family with this “backward” designation.

I have my dad’s last name, and because last names often indicate a person’s caste, I understood that it would be easier to pass as a Nair while in India. I put the article down and did my best not to think about it further. That is, until I began working on this series.

Embracing caste in America

It turns out that there are Indians who still embrace their caste status, even in America. This is what led me to a resort outside Chicago, surrounded by golf courses and McMansions, to report on the Nair Service Society of North America’s biennial convention.

The original Nair Service Society, or NSS, was founded a century ago in Kerala. The August 2018 convention of the NSS of North America, was the organization’s third major gathering. While approximately 60 families have attended previous conventions, in 2018, the NSSONA reported over 180 families in attendance.

A casual observer could be forgiven for assuming that a wedding was taking place. From morning until night, most convention-goers were dressed in the kinds of eye-catching jewelry, saris and other glittering garments often worn at Indian weddings. The convention schedule kept the well-dressed attendees on the go, starting with prayers at 6:30 a.m. and ending with a formal gala that ran well past midnight. The second day of the three-day gathering included a dance workshop, a sari sale, a Nair history and culture quiz competition for kids, a women’s empowerment talk, a play about a queen from Kerala who fought against the British, a fashion show and a competition for the title of Mrs. and Mr. Nair.

For the most part, it was a festive atmosphere, where the most visible elements of Kerala’s culture were on display — language, dance, food, music, attire. Culture, community and unity are the three words I heard spoken repeatedly, both in the speeches and my interviews with attendees.

This was a gathering of people of the same caste, however, and beliefs about caste lay deep within what anthropologists call the “cultural iceberg.”

The caste system came up, explicitly and unexpectedly, at an event billed as a “youth seminar.” It was a rambling, half-hour lecture intertwining religious history with what was meant to be career advice, led by a man closer to middle age than “youth.”

“These youth growing [up] in US will always ask the question, ‘Why there is casteism in India? Why there is Sudra, why there is Vaishya, why there is Kshatriya and Brahmin?’” he asked, listing the four main castes in reverse order, bottom to top.

The man continued, making no mention of Dalits, the lowly outcastes formerly known as “Untouchables” in the religious and social hierarchy of Hindus. “This casteism is not to be taken literally,” he added. “This system is followed throughout the world, including US.”

He segued to comparing the caste system to the structure of a company — with manual labor at the bottom, management and sales in the middle and upper strata, and executives at the top. It was a muddled explanation, both a justification of caste and a dismissal of its realities. There was no time for questions at the end, and it was not clear whether anyone present disagreed with his stance. But during a one-hour panel discussion called “Nair Vision,” others’ opinions become apparent.

The Nair Vision event was designated as a question and answer session, with a handful of people on stage asking questions across a range of issues. How should NSSONA be organized? What is the organization’s stance on the Indian Supreme Court’s Sabarimala ruling, which struck down a ban on women ages 10 to 50 at a Hindu temple in Kerala? Does the volume of pro-BJP messages on NSSONA social media platforms suggest that this non-political Hindu organization supports India’s ruling Hindu nationalist party, the Bharatiya Janata Party?

Related: Two women enter a Hindu temple in India, defying ancient ban and sparking protests

Shreya Menon, an accounting student from New York, was the youngest person on stage. She began her question by stating that she is a proud Hindu, but has concerns about the hierarchical standards in Hinduism as they pertain to caste.

“I am uncomfortable with practicing the segregation that comes with being part of the caste system,” Menon said. “So, my question is: What can NSS do to align with the youths’ beliefs so that we can one day be proud to carry on this organization into the future?”

The person assigned to answer Menon’s question confessed his own discomfort with caste.

“The subject of the caste system makes us all feel very uncomfortable,” he said. “Yes, it has got a little inhuman quality.” The caste system should be abolished, he urged, “as the great Ambedkar said.” This was in reference to B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit who was the principal author of India’s 1950 constitution. Ambedkar had argued for the founding document to ban caste, but Gandhi prevailed in having it only ban discrimination based on caste.

The man then turned to another topic that came up frequently at the convention: so-called “reverse discrimination.”

“But now, there is reverse discrimination in Kerala, and, so it is time that NSS should take an active step in trying to bring everything to parity,” he said.

Related: Suraj’s shadow: Wherever he goes, his caste follows — even in America

India has the world’s oldest affirmative action program, which is authorized in the constitution. Nearly all the Indian immigrants I spoke with at the convention complained that the quotas or “reservations” help Dalits and members of lower castes get jobs and into universities, but make it harder for Nairs to do so. This is a widespread sentiment among upper and dominant caste Indians.

Later that day, I followed up with Menon. Was she happy with the answer that she received? Menon weighed each word before answering.

“I think this question deserves more, because it cannot be answered in one minute or two minutes,” she replied. “I wasn’t content with the depth of the answer, but I was very appreciative of the fact that the viewpoint was shared.”

“Asking questions that you don’t know what the answer will give you, maybe that’s something people should do often,” Menon added, “especially at a caste convention.”

Caste and confusion

I arrived at the NSS Convention with one question: What brings you here?

I left with a much bigger question: What are the stories we tell ourselves?

Sreedharan Kartha, a retired scientist from the University of Chicago who lives outside the city, comes from a small caste in Kerala called the Karthas, who consider themselves to be slightly above the Nairs and just below Brahmins. For the most part, Kartha regards caste-based gatherings with bemusement. He came to the NSSONA convention, he said, to satisfy his nostalgia for the food and music of Kerala.

On one point, however, Kartha is insistent. Though Nairs assert that they are Kshatriyas, or the main caste below Brahmins, Kartha says that Nairs are Sudras, the lowest one can be without being a Dalit. “When I was very young,” Kartha said, “the kitchen was the most sacrosanct place in a household. Nairs were not allowed in our kitchen.”

“I’m not saying this because I’m not a Nair,” he added. “My wife is a Nair, but how does it matter now whether they are Kshatriyas or not?”

It matters because, by accident or by design, caste seems to feed off confusion.

The caste system is often loosely grouped into four or five main divisions. There are, however, thousands of castes and tens of thousands of sub-castes within the Hindu hierarchy, making a strict ranking of them nearly impossible to find. If Nairs and others can be kept busy disputing who is higher than whom, aren’t they then too busy to ask questions that might deprive caste of its power?

Fifty years ago, my parents thought that caste was on its way to becoming an artifact of history. Today, caste hierarchies remain at their most rigid when it comes to marriage. As it turns out, the Nair Service Society of North America embraces the tradition of marrying within the caste. In 2017, the organization launched a matchmaking website called Matrimony 4 Nairs. To date, well over 200 potential brides and grooms have signed up.

Follow the “Caste in America” series.