30 years later, this Korean adoptee finds ‘home’ again

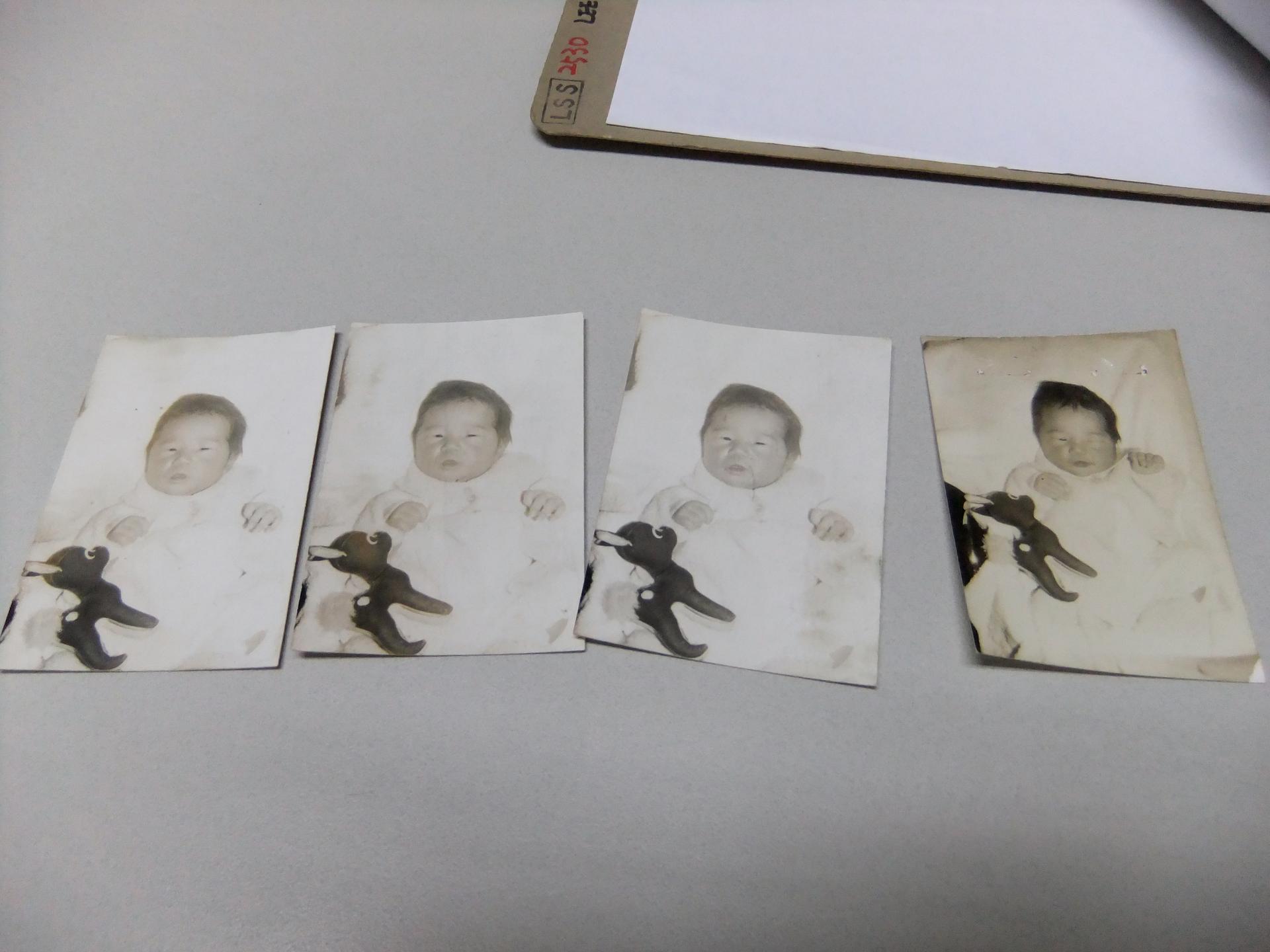

Baby photos of Shawyn Lee that had been kept in Lee’s file folder for 30 years.

I was born on January 14, 1978, in Seoul, South Korea. Two days later I ended up at Korea Social Service, an orphanage in Seoul. On July 6, 1978, I arrived at Minneapolis International Airport into the loving arms of my adoptive parents, facilitated by Lutheran Social Service in Minnesota. My adoption was finalized on April 23, 1979, and I became a citizen of the United States on April 26, 1980. For more than 30 years I never gave any of this much thought.

Then, in 2010, I was invited to speak in Seoul — in a country I hadn’t seen for decades. This is the story of when I first touched the land in South Korea.

Related: For many, international adoption isn’t just a new family. It’s the loss of another life.

It’s late morning on an overcast, steamy August day in Chicago in 2010. I have been up since 4 a.m. Buckled firmly into my seat on the largest airplane I have ever been on, I am anxiously awaiting our departure from the gate. The stale airplane air makes my stomach a little queasy, and occasionally my seat lurches forward, victim to the little feet kicking it from behind.

The scenery outside begins to move as we push away from the gate. Slowly the plane turns toward the runway. We sit for a few minutes. I watch the cars speed past on the highway just beyond the airport. The world outside is full of commotion. In some ways, time seems like it has sped up this morning. But inside the plane, it feels like time has stopped.

We rumble down the runway, gaining speed for takeoff. I feel every bump in the pavement. I hold on to this feeling — it is comforting and familiar because I am still on the ground, I am still home. Then, I feel my body pushed back into the seat and my stomach drops as we lift off the ground. Skyward bound, and eventually westward, I am moving forward in time in one sense, yet back through time in another. A country I know nothing about is calling my body to it. I am going home.

My body knows it is home when it touches the land in South Korea, but other than the physical connection to place, everything else — including my mother tongue — is missing. I left my country when I was an infant, and like an infant, all I can do to communicate with my people is point and try to utter the few words I know in broken Korean. The disconnect between what my body remembers and my inability to fully be Korean in my home country is sad and confusing.

Read Shawyn’s piece on the darker history of international adoption to America

Every three years, the International Korean Adoptee Association hosts an international conference by and for Korean adoptees from all over the world. This is my first time attending. I am presenting on my experiences of being a Korean adoptee and being queer. Trying to make my way through a home my body remembers, but one in which I have no conscious memory of, is hard enough as an adoptee — ibiyang. But I also have to contend with being queer in a country where the LGBTQ community is still very much underground. It’s odd and unsettling to feel so out of place for so many reasons in my motherland.

I visit the orphanage where I stayed for the first six and a half months of my life. With a crude map in hand, I try my best to communicate with the cab driver in broken Korean, English and some pointing. I arrive at Korea Social Service on a hot August morning. The building towers over me as I stand at the base of the stairs leading up to the main entrance. Its brick facade is stark against a dull sky.

At this moment it isn’t curiosity or even nervousness that washes over me, it’s an overwhelming feeling of sadness. Why? What is my body remembering? Why can’t the words be in my brain? I walk up the stairs and enter the building. Immediately I am ushered into a small meeting room. I sit alone. No lights are on. The noise of the air conditioner drowns out any conscious thoughts in my head. The room feels heavy and lonely as it wears a dreary grayish blue hue from the ambient light. I shiver under the icy breath of the air conditioner.

The director of KSS enters the room after a little while. She is a short, petite, middle-aged Korean woman. Her black hair hangs casually just above her shoulders. Her eyes look tired but kind. She is clutching two file folders to her chest. One is my sister’s, and the other, mine. I stand to meet her. She is a bit taken aback by my appearance. I tower over her. My androgynous appearance doesn’t look like a grown-up version of the little girl who is in that folder. I assure her I am that same little girl, now grown. We sit down opposite each other at the small table in the meeting room. She gently lays the folders down on the table. I read the label: LSS 2530 LEE Cho Hee. There I am, laying on the table, closed up for 32 years. That was me. My history. My answers. My life.

Inside the folder are faded brown papers all written in Korean. I want so badly to touch these pages, leaf through my story. I wish I could gather up the contents, clutch it to my chest and absorb the residual energy. But I am instructed that I am not allowed to touch anything. My interactions with the KSS director are stoic and businesslike. I want to make sure I ask all my questions and understand everything that she is telling me.

I was born Lee, Cho Hee on Jan. 14, 1978, at 9 a.m. in a clinic in Seoul. My mother, Lee, Eun Joo was a single, unwed mother. She was 24 when she had me. According to my file, she did not want to share much about her story with the social worker from KSS. There is no information about my birth father.

I had always been told that I was abandoned at a police station with a note pinned to my clothes listing my name and birthdate. My file told a different story. On January 16, 1978, two days after I was born at the clinic, I was brought to KSS. There is no information about where I was for those two days. The story of being abandoned at a police station is common among Korean adoptees around my age — it helped expedite the international adoption process by leaving fewer questions to answer.

After reviewing my file, we go up to the second floor of KSS where the nurseries are. There are four infants and a 1-year-old boy with developmental disabilities in the room. I walk past the director into the room. She whispers gently to me, “One of these cribs was probably yours.” I make my way over to the row of cribs. Fighting back some tears, I run my hand along the rails. I feel the cool metal bars and breathe in the stale nursery air, filling my lungs and my body with memories of yesterday. One of the babies looks like me in the pictures I have from the orphanage. I feel as if I am looking at myself. My heart fills with a heavy sadness as I think about these children and their missing stories.

We tour the rest of the grounds. The other buildings on the premises are abandoned. When I was here in the late 1970s, KSS was home to around 200 children. There were only 50 employees who worked at the orphanage and no volunteers. During my visit, only five children are there, and two volunteers. Today, foster homes have replaced the need for orphanages. This place feels empty and desolate. The abandoned buildings are in various states of dilapidation and the grounds are patchy and unkempt.

We walk to the building I lived in while here. My eyes are seeing the same things now that my tiny infant eyes saw for the first six months of my life. I peer inside the windows. It’s dark and hollow — gutted. I try to listen for the sounds of children playing, workers scurrying around, babies crying. Nothing. The energy has seeped away.

More than three decades ago, I left this place on a plane bound for the United States, my home. More than three decades later I come back home to discover the story of my beginnings. As my trip comes to an end, I find myself desperately clinging to this place. But no matter how much I change up my grip, I feel it slipping away. I never want to forget this place. I need to feel and experience South Korea just as I do now even when I am back in Minnesota.

I was at home in Minnesota before I came to Korea, and a stranger in my homeland. Now I feel like I am home in South Korea and will be a stranger back home in Minnesota.

I started this journey holding on to every bump on the runway before we left the United States for Korea. Now, the jolt as the wheels touch down back in Minnesota marks a jarring end to an unforgettable journey and one that I will continue to process for the rest of my life. My eyes fill with tears and the lump in my throat lingers as we taxi to our gate. I feel more whole and complete now knowing that I left a good chunk of me in South Korea. Someday, I’ll be back again.

Editor’s note: Shawyn Lee is an assistant professor in the Department of Social Work at the University of Minnesota – Duluth. As a critical adoption scholar, Shawyn’s work incorporates archival research, critical pedagogy and intersectional identity politics based on Shawyn’s personal experiences as a queer Korean adoptee. Read Shawyn’s piece on the difficult history of international adoption to America.