‘Hope to hopelessness’: Will government step up after second storm?

Cars sit in flooded waters due to Hurricane Florence in Lumberton, North Carolina, Sept. 18, 2018.

Dianne Powell is living a recurring nightmare.

In October 2016, Hurricane Matthew filled her brick house with rainwater — up to her waist. The storm inundated her town, engulfing homes and highways and causing $4.8 billion worth of damage statewide.

Editor’s note: This story is part of the Center for Public Integrity’s “Abandoned in America” series, which profiles communities connected by their profound needs and sense of political abandonment at a time when President Donald Trump’s administration has declared the nation’s war on poverty “largely over and a success.” Part I: How ‘The Wall’ could kill a Texas city

She rebuilt. Then Hurricane Florence struck and swamped her home again.

Powell is faced again with the wrenching process of mending what two storms destroyed within two years. She’s unsure how she’ll pay for repairs.

On a September afternoon after the latest flood waters had receded, she carefully stepped over her loose floorboards, buckled and haphazard against walls sporting a new foot-high yellowish-brown watermark.

As Powell surveyed the interior of her new home now damaged — the burgundy walls, the matching wine-patterned kitchen towels and curtains — she lamented what could have been.

“It was all so pretty,” she said with a sigh.

Powell’s is the story of countless residents of Robeson County, whose families, friends, neighbors and congregations provided support after Hurricane Matthew when the government’s pathways to recovery left many overwhelmed, left behind or never heard.

And they wonder: Will it be any better this time around?

From a place that feels worlds away from Washington, DC, navigating a federal bureaucracy has proven difficult at best, and especially fraught for those who need it the most.

Robeson County was already struggling when Hurricane Matthew hit, and it hadn’t gotten back to that already-low baseline when Hurricane Florence rolled through the region.

It’s among the poorest (with 30 percent of residents living below the poverty line), unhealthiest and most dangerous counties in North Carolina, beset with issues more typical of inner-city neighborhoods despite its status as a largely rural community of a little more than 130,000 people. The hurricanes’ flooding displaced thousands from their homes and cut off access to their medicine. Looters waded into rushing water filled with snakes and alligators, breaking into liquor stores and houses, nabbing electronics and jewelry, residents said.

“All a storm does is wash to the forefront the problems that already exist in that county, in all counties,” said Cliff Harvell, disaster response superintendent with the North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church.

In interviews this summer and fall before and after Hurricane Florence many residents said they found attention and assistance for their problems on the local level, but didn’t feel that same support from their federal lawmakers.

What they said they saw and experienced were a handful of speeches, inflated promises, delayed funds and not enough repaired homes.

Struggle with FEMA

After Hurricane Matthew, Powell struggled for months to secure government assistance, but received confusing and conflicting information over the course of a dozen meetings with Federal Emergency Management Agency officials. Exasperated, she eventually stopped trying to rebuild her home with FEMA aid.

“You work all your life, you have a decent home. And you go in front of FEMA and they sometimes look like they couldn’t care less, or like they think you’re lying,” said Powell, 64, in July. “It was just so painful. I said forget it.”

Powell’s cousin suggested another route for help: the Baptist church. Using her savings, some flood insurance money and a $20,000 low-interest Small Business Administration disaster loan, a church recovery group finished fixing Powell’s home in July 2018 — in just a few months — using volunteer labor.

Even before Hurricane Florence, FEMA officials explained they do the best they can amid calamities such as these, and that it’s the “nature of disaster” that some people will be lost in the process.

“Unfortunately, there are times when not every need is met, but our staff works really hard to try and avoid that,” said Libby Turner, the federal coordinating officer for Hurricane Matthew at FEMA, when asked about Powell’s plight and the struggles of those like her. “And it’s sad, there are times when I stumble because it just makes me want to write [their names] down and go find them.”

Now, it’s unclear how much federal aid Robeson County will receive for Hurricane Florence, as the dollar figures change by the hour while the recovery process just begins to take shape.

As of Oct. 8, Robeson County residents received $5.9 million in state and federal grants to help rebuild or to cover other storm-related expenses, according to FEMA. And Gov. Roy Cooper announced in late September that Robeson would be one of 28 North Carolina counties to get a share of $18.5 million from the US Department of Labor to hire state residents to do recovery and cleanup work.

For Hurricane Matthew, FEMA doled out more money to Robeson County than any other county in North Carolina for public projects and to help people rebuild, according to FEMA data. And the Small Business Administration offered Robeson residents and businesses more than $21 million in low-interest disaster loans, the second-largest amount in the state, though the agency doesn’t release data on how much of that available amount people actually borrowed.

Dozens of other government agencies also aid communities’ recovery in the wake of a hurricane. They help, but it’s also challenging, if not nearly impossible, for many people to navigate such a system in the midst of post-disaster chaos.

“The disaster recovery process has been more traumatic for some than the trauma of the disaster itself,” said Mac Legerton, co-founder of the social justice nonprofit Center for Community Action, which is involved in hurricane recovery efforts, among other issues.

Not connecting to Washington

Robeson County’s disconnect with Washington, DC, began accelerating in the early 1990s. It was then that President Bill Clinton implemented the North American Free Trade Agreement, which beginning in 1994 tore down trade barriers between the US, Canada and Mexico — and arguably hastened the decline of local industry and sent local jobs overseas. Robeson County lost more than 8,700 manufacturing jobs from 1993 to 2003, according to an analysis of North Carolina Employment Security Commission data.

This came around the same time the federal government was waging war on tobacco, the region’s cash crop. The county had 17,000 acres of tobacco farms in the 1980s. But that dwindled to only 2,000 acres a few decades later after President George W. Bush signed the Tobacco Reform Act in 2004. The program deregulated the industry and paid out farmers who formerly grew the crop.

This economic hardship — disdain for NAFTA, in particular — contributed to why a majority of Robesonians voted for President Donald Trump, only the second Republican president to carry the county in more than 100 years. Trump railed against the trade deal during his campaign and finalized a new deal Sept. 30 called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which notably affects car manufacturing, dairy products and labor unions. It’s expected to take effect in 2020, if Congress approves the deal.

Political tumult continued into the 2018 midterms as the county’s congressman, Republican Robert Pittenger, became the first incumbent nationally that voters booted out this election cycle. Former Baptist preacher Mark Harris snagged the nomination by 828 votes and will face Democrat Dan McCready, a solar energy executive, in November.

But only one-third of Robeson’s 75,000 registered voters cast a ballot in the primary, highlighting a major disconnect — at both ends — between Robeson and the federal government. It’s to be seen if either candidate will inspire this politically detached population to vote for him in a pivotal election where every ballot matters — especially when hundreds of residents are still in shelters.

Despite desperately needing hurricane recovery help and economic stimulation, Robesonians don’t take advantage of the usual routes to reach politicians that could change their fortunes, whether through the ballot box or by contributing money to political campaigns, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis.

In Robeson County, about 3,100 fewer people voted during the 2016 presidential election than during the 2012 presidential election. The drop, residents said, can partly be attributed to the community still reeling from Hurricane Matthew a month before Election Day 2016.

Only about 53 percent of Robeson’s registered voters voted during the 2016 general election. That’s the second lowest participation rate out of all North Carolina counties, behind only Onslow County. And when looking at the number of votes cast in 2016 compared to voting age citizens, Robeson ranks among the lowest counties in the entire United States, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of Census Bureau and OpenElections data.

Averaged out, Robeson residents donated about 75 cents a person to politicians, parties and political groups, making the county also one of the least generous in terms of political giving. With a $31,000 median income — barely half that of the average US household — that’s not necessarily surprising. But politicians don’t often fundraise in areas that don’t generously contribute money, and therefore, may not show up as often as they might if the area was flush with cash.

Municipalities in Robeson County, as well as the county itself, could hire lobbyists to advocate for their interests in Washington, DC. Robeson County spent about $20,000 on federal-level lobbying efforts for “community facilities” in 2017 and has yet to report any lobbying expenditures worth more than $5,000 this year, according to congressional records. Lumberton and Maxton, a small Robeson County town, reported lobbying in small amounts earlier this decade, but no Robeson towns appear to have paid K Street firms in the past few years.

Pittenger does not have a physical district office in Robeson County, and he rarely advertises in-person office hours or visits to the region. Pittenger hosted two public town hall meetings in Robeson County since 2016, according to congressional data service Legistorm data and Pittenger’s office.

Pittenger’s last Lumberton town hall in August 2017 didn’t go smoothly, Lumberton city councilmen Chris Howard and John Cantey said. Pittenger struggled to answer questions about Hurricane Matthew aid and residents criticized his comments supporting Trump’s speech about racial violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. Pittenger appeared at 16 events across his district and four “virtual” town halls where people could call in, tweet at or message Pittenger, over that time period, according to Legistorm data and Pittenger’s office.

“Congressman Pittenger has spoken up on behalf of Robeson County at every opportunity in the preparation, disaster, and recovery phases, and he will continue to do so through his last day in office,” Jamie Bowers, Pittenger’s deputy chief of staff and communications director, said in an email.

Though residents felt underwhelmed by the response from their politicians, their federal delegates say they fought for funding and provided support on multiple fronts.

Bowers said Pittenger is in frequent contact with local leaders and passed on requests to the appropriate government agencies, advocated for Robeson aid with House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy and House Majority Whip Steve Scalise and pushed the Department of Housing and Urban Development to send a representative to Robeson County.

A spokesman for Republican Sen. Thom Tillis said Tillis surveyed the damage in Robeson County days after Hurricane Matthew hit, and “spearheaded” the effort with Sen. Richard Burr to grant more than $400 million in federal funds for the state during Hurricane Matthew and pass a bill with $1.14 billion for Hurricane Florence. This billion dollars includes a provision helping communities that were hit hard by both hurricanes Matthew and Florence.

Tillis’ staff keeps in contact with Robeson County officials, and his DC office hosted county leaders to hear about their needs, spokesman Daniel Keylin said. Tillis and Burr met with Trump and Cooper in Havelock, North Carolina, visited people affected by Hurricane Florence and both shared information about hurricane preparedness and how to apply for aid.

Some groups are making progress in working the system: Robeson County’s Native American Lumbee tribe continues to lobby the federal government for full federal recognition that would open up additional funding streams to the tribe, an effort Pittenger, Burr and Tillis support.

Though it has not yet achieved the goal, the tribe is making headway in other areas: The Trump administration invited Lumbee Tribal Chairman Harvey Godwin Jr. to attend the 2017 inauguration and festivities, and North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper hired Godwin’s son, Quinn, as his regional outreach liaison officer. Pittenger and the candidates vying for his seat all marched in the Lumbee Homecoming Parade in July, appealing to this mass of voters in one of the most diverse rural counties in the US.

Demographically, Robeson is 30 percent white, a quarter black and almost 40 percent Native American. It’s also home to a small but growing Hispanic community.

“Sen. Burr was personally engaged as Florence hit,” said Lumbee Tribal Chairman Harvey Godwin, Jr. “He has my cell phone number, we talked every day, and he brought in an Indian American liaison to help tribal members and businesses get help.”

Godwin said that although the Lumbee population could “do a lot better” with turning out to vote, it is beginning to recognize its potential.

“We’re a big voting bloc that can influence an election and are finally able to realize that power,” Godwin said. “In the past, we never got the return on investment for our support, but we will hold them accountable for their promises now. I think that’s more powerful.”

But overall, large pockets of the population are not tuned in to political matters.

“When I’ve been canvassing … I ran into people that don’t understand if their county has an election and when is the next election, or if they’re a Democrat or Republican,” said Adrienne Kennedy, a community organizer who door-knocked for the Democratic Party. “You gotta bring them up from that.”

But it’s hard to know who to vote for when you have more pressing problems, like trying to get back into your home.

Missed deadlines

Some local politicians, such as Lumberton City Councilman Columbus “Chris” Howard Jr., face the same situation as their constituents: waiting to rebuild and feeling disconnected from Washington. Every few moments during a tour of the town this summer, Howard pointed to a house he drove past, explaining where the owner is now or the status of the rebuilding process.

“I know the people — I’ve been here for 40 years,” he said. “This person was in the shelter with us. This house is supposed to be torn down and rebuilt. She has a second mortgage, so she can’t afford to do anything. This fella here has gotten into his house within about 12 months.”

Although pumps helped suck away the more than a foot of water that fell on Lumberton, remnants of the destruction still speckled the streets over the summer almost two years later.

A concrete foundation with no structure on top.

Depiped toilets placed on porches.

The shuttered West Lumberton Elementary School.

Entire culs-de-sac of public housing without a car in the driveway or inhabitant to be seen.

Countless numbers of “Thank you Jesus” signs.

Piles of white silt from the Lumber River and sand from under Interstate 95 covered residents’ yards. (“It looked like fresh snow. Or a beach,” one resident said.)

That was before Hurricane Florence. A week after the second major hurricane hit, truck-sized pumps running nonstop for days extracted most of the floodwater, leaving reflective puddles throughout Lumberton.

The most immediate relics of Hurricane Florence were the enormous toppled trees — roots and all pulled from the ground — and the strong stench, of decaying leaves or rotten eggs and meat. A gray blanket of flaky muck covered gardens and lawns and grass, giving most plants an appearance of decay. Mosquitoes swarmed the town, breeding in the pools of water left behind.

Howard himself couldn’t escape either storm. As tempest-tossed residents fled for higher ground during Hurricane Matthew, burglars stole most of his family’s valuables, such as his wife’s jewelry and their flat-screen TV.

His house, after being treated for mold after Hurricane Matthew and mostly stripped out with the help of $11,000 from FEMA, served as storage for his furniture and landscaping supplies. That was until Hurricane Florence rendered most items beyond saving.

Howard and his wife, Gennifer, bought and moved into her parents’ house as the couple waited for the FEMA-funded project to tear down, then rebuild, their home.

Then Hurricane Florence arrived. And FEMA officials couldn’t answer his questions if that work would ever start.

“It’s confusing to me when I went to ask [FEMA]. Nobody knows anything, you can’t give me no answers,” Howard said. “I’m through with this house. I want them to buy it. There was hope. Hope to hopelessness. This dream is gone.”

The Howards moved back into their home on Spruce Street after 20 days in a hotel, an expense they could no longer afford. There is still no air conditioning and hot water.

“We still don’t have all the money promised to us from the last storm,” Howard said. “So how long will it take us for Florence? Five years? More?”

Politicians are still scuffling over perceived mismanagement of relief money earmarked for Hurricane Matthew recovery.

Republicans accuse Cooper, the Democratic governor, of holding hostage federal funds necessary to rebuild the region. As of April 2018, the state had not spent any of a $236 million grant awarded the previous fall from the Department of Housing and Urban Development community development block grant program, according to an investigation by WBTV. Federal agencies and lawmakers pass down disaster funds to the state, which then has the responsibility of spending or passing them to local entities.

“It is deeply concerning that these federal disaster dollars are not being released when many North Carolina families are still living in temporary housing,” Republican US Sens. Burr and Tillis and Reps. Walter Jones, Virginia Foxx, Richard Hudson, David Rouzer, George Holding and Pittenger wrote in May in a joint letter to the governor. “Any further delay may also have unacceptable consequences on any future disaster aid requests.”

“We are confident that North Carolina will have sufficient federal funding appropriated by Congress to assist with the long-term recovery efforts, and we are hopeful the state learned valuable lessons from the slow pace of Matthew [community block grant] spending,” Tillis spokesman Daniel Keylin said in an email to the Center for Public Integrity.

A July WBTV investigation found that although North Carolina and South Carolina received block grant funds around the same time, South Carolina — also hit by Hurricane Matthew — put 145 families into homes and sent out 459 award letters. Only one family in North Carolina received a check.

After a June deadline passed without any construction, North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore, a Republican, reconvened the House Select Committee on Disaster Relief in July to investigate the holdup. Cooper’s office said that when Hurricane Florence hit, more than a dozen construction projects were in the works and $295,850 had been awarded to 24 families in Robeson County through the community block grants.

“The state has already begun contacting people who experienced flooding by both Matthew and Florence to learn about additional damage and update awards,” Ford Porter, the governor’s press secretary, said in an email. He said Cooper is in contact with Trump and FEMA and HUD officials to make sure the state receives assistance as quickly as possible.

This HUD grant, to be sure, is just one source of money from the federal government. FEMA gave Robeson County $26 million for public projects, such as debris removal and rebuilding public buildings or services for Hurricane Matthew, and will begin accepting proposals for Hurricane Florence in the coming weeks. The agency also promised almost $26 million in “individual assistance” grants in Robeson for Hurricane Matthew, which cover housing-related expenses and other things such as medical care, child care or household items.

“Following two 500-year floods, the state must emphasize the need to rebuild smarter and more resilient — particularly in communities at risk of flooding,” Porter said. “Local, state and federal partners came together to prepare and respond to Hurricane Florence. Now we must continue to pull together to quickly deliver assistance and support to the survivors of this storm.”

Voting: the last thing on their minds

Hundreds of Robeson County residents remain in shelters, unclear when they can return to their homes.

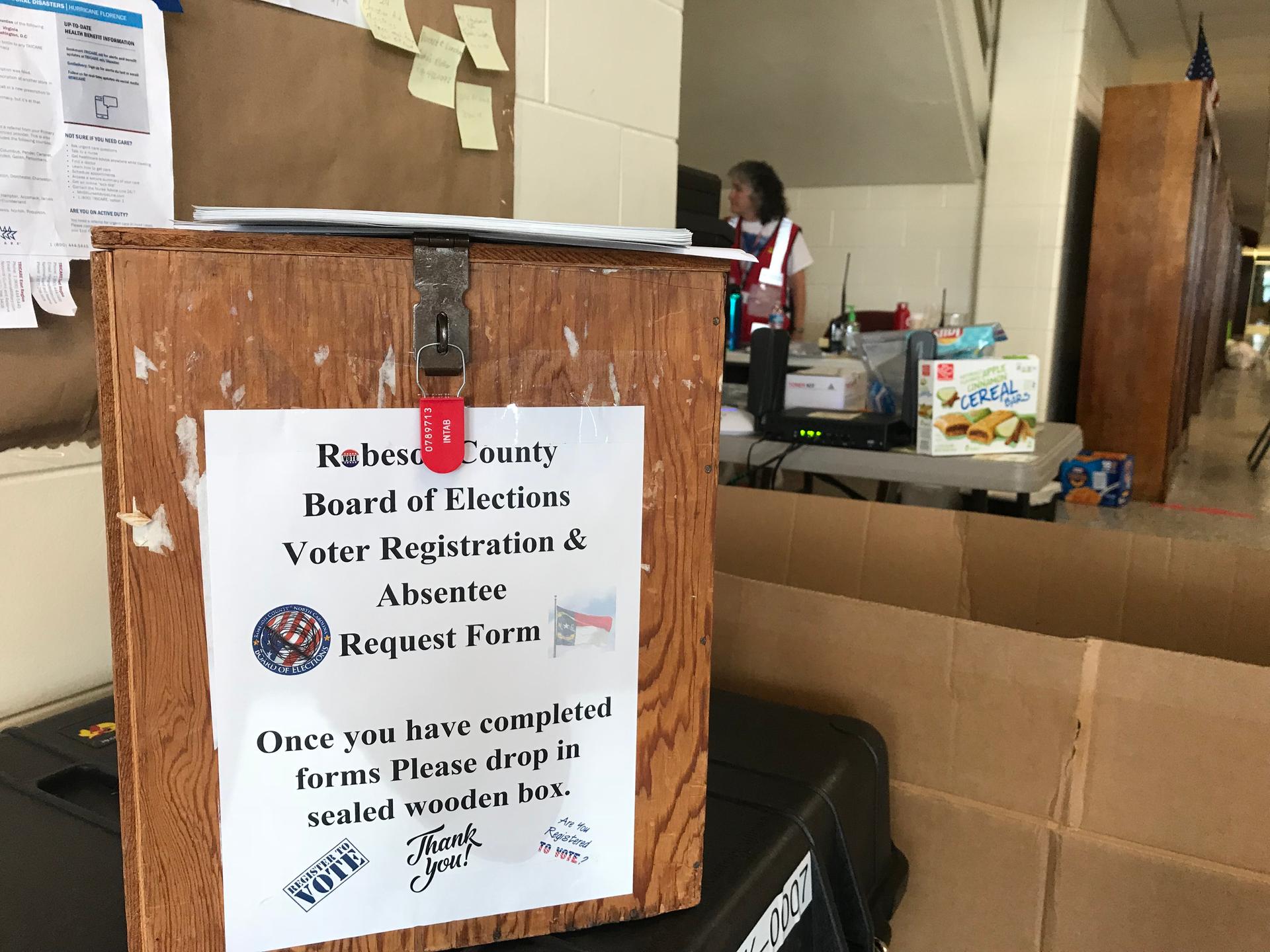

Local and state elections officials, meanwhile, say they have plans in place to make sure those who are displaced know where to vote or have the forms they need to request an absentee ballot.

The North Carolina State Board of Elections mailed out thousands of absentee ballot request forms, are surveying polling sites to make sure they are usable (three polling sites in Robeson County had to be moved due to mold and other hurricane damage in 2016) and sent a letter “summarizing election deadlines and requirements” to the governor and statehouse leaders. It also updated its website with information about how to vote after Hurricane Florence. Many are skeptical of these strategies.

“Do you think you’re going to open up your mail and look at something from the Board of Elections, needing your vote?” Howard said. “What is more important to you at that period of time? Not that.”

Lumberton Councilman John Cantey Jr. said, “Mostly it’s gonna be your Democratic voters that are lost because these people are in shelters. They in Fayetteville, they in Charlotte, they with family and friends, they moved out, moved away.”

Red Cross shelter supervisor Jennifer Seely said despite the circumstances, she registered to vote many people at the Lumberton High School shelter. She encouraged others to call their representatives to express anger that they were flooded again.

After Hurricane Matthew, the Democratic Party sued and successfully got the deadline extended five days in 2016.

So the Rev. T. Anthony Spearman, North Carolina NAACP’s president, sent a letter on Oct. 1 to Cooper and elections officials requesting “immediate action to ensure that those suffering from this disaster are not denied access to the polls.” Specifically: he asked that they extend the voter registration deadline at least five days, to Oct. 17, for hurricane-ravaged counties, including Robeson.

“We know from past experiences in this state and others that, without swift intervention by the state, natural disasters can disrupt and deny voting opportunities,” Spearman wrote.

Two days later, on Oct. 3, Cooper signed bills that pushed back the voter registration deadline for hurricane-hit counties by three days to Oct. 15, in addition to providing other Hurricane relief measures, such as $50 million for immediate relief efforts.

The race for North Carolina’s District 9

With Pittenger, the three-term incumbent, out of the picture, Robeson County’s next congressional representative — Republican or Democrat — will be a resident of Charlotte, North Carolina’s largest city.

Republican Mark Harris is a former Baptist preacher who committed to joining the ultra-conservative House Freedom Caucus.

Democrat Dan McCready is a former Marine and solar farm company executive endorsed by the moderate Blue Dog Democrats.

Starting in Lumberton, it takes about two-and-a-half hours and half a tank of gas to reach the outskirts of Charlotte. North Carolina’s 9th District spans eight counties, some in part, and the nominees live in Charlotte, in Mecklenburg County, the southeast sliver of which is included in the district after North Carolina redistricting in 2016.

One Robeson resident, the executive director of the North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church, Steve Taylor, described the disconnect he felt from his next congressional representative by asking, “What does Charlotte have to do with me?”

This seat hasn’t been occupied by a Democrat since the mid-1960s, although it’s covered different swaths of the state over the years. But as Democrats attempt to ride a blue wave and take control of Congress, North Carolina’s District 9 increasingly seems to be within the party’s reach. And in August a federal court ruled the district map unconstitutional, saying it was gerrymandered in Republicans’ favor, though the map won’t be redrawn until after the 2018 midterms.

The Cook Political Report rates the race as a toss-up, and Sabato’s Crystal Ball says it leans Democratic. McCready has outraised Harris by almost threefold through the first half of the year, $2.7 million to $930,000.

McCready also has national help. House Majority PAC, a super PAC that aims to elect Democrats into Congress, has so far spent almost $340,000 to produce online ads criticizing Harris’ support of the Trump tax overhaul, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics and the FEC. Democratic nonprofit group Patriot Majority USA released a similar ad about the tax plan, spending almost $305,000. Outside groups spent the most money in this race compared to any other in North Carolina.

Harris received some last-minute ammunition: Donald Trump Jr., the president’s son, headlined a fundraising luncheon this month for Harris in Charlotte along with Freedom Caucus Chairman Mark Meadows.

Harris, despite nabbing only 597 primary election votes in Robeson, a county where a majority of registered voters are Democrats, said he has hope for more support in the general election. He said Robeson is seeing dramatic changes, such as electing state Sen. Danny Britt Jr., the first Republican to represent Robeson since Reconstruction. (Several Democratic voters said they’d voted for Britt because of his hands-on help during Hurricane Matthew.) He also pointed to Robeson’s 86 percent support in a 2012 vote on a state constitutional amendment Harris pushed that would have defined marriage as being between a man and a woman.

While his campaign website exclusively focuses on national issues, Harris told the Center for Public Integrity he hopes to boost Robeson County’s economy with transportation and infrastructure projects.

McCready, for his part, has been courting Robeson County’s Lumbee residents. He marched in the Lumbee Homecoming Parade in July with a large banner printed with “Full federal recognition now!” to appeal to the local Native American vote.

“The politicians in Washington have paid a lot of lip service to the Lumbees but haven’t gotten the job done,” McCready said in an interview with the Center for Public Integrity.

Politicians simply showing up means a lot to Robeson County residents.

Many Lumberton residents told local papers they felt excited when Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter, visited a local Baptist church on Oct. 3 and spent 12 and a half minutes serving meals to waiting cars.

But Lumberton locals said they didn’t see enough of their federal representatives after Hurricane Matthew, and have yet to see much of them or the candidates since Hurricane Florence.

The Harris campaign organized a food drive for eastern North Carolina, according to his Twitter account. McCready said he visited a Lumberton shelter and brought bottled water to the town and to nearby Pembroke.

“After having spent time with folks on the ground in the aftermath of Florence and over the campaign, I can say that nowhere in the country has [a place] been forgotten by Washington politicians more than Robeson County,” McCready said. “They deserve better.”

Burr’s office said Burr met with the mayors of Spring Lake and Lumberton and toured the regions at the end of September. Tillis’ office sent a representative to Lumberton and Allenton in the beginning of October and plans to visit Lumberton to survey damage soon.

Many pointed to Cooper’s tour of Lumberton after Hurricane Florence hit, a day after the governor met with President Trump.

“The president said he would be 100 percent there for us for the long haul,” Cooper said at the time. “So I’m going to take him at his word, and hold the federal government to that. We know that we’re going to need significant help. This is going to be a multibillion-dollar effort.”

One of the reasons they supported Trump during the 2016 election, some residents said, is because they saw a Trump bus in town and Trump volunteers, including Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara, handing out water bottles to survivors.

“We didn’t see Hillary’s bus,” said Kennedy, the community organizer, who voted unenthusiastically for Clinton. She feels hopeful about McCready, who she has spoken with through her connections with the North Carolina Justice Center.

“I wish politicians would be like an undercover boss, and just camp out,” Kennedy said, referencing the popular television show. “The boss made the initiative to go down low, to see what were the nuts and bolts.”

‘I’ve got to live’

Dianne Powell’s life fundamentally changed after Hurricane Matthew.

She had recently retired from her job as a jail guard with the county sheriff’s department. Instead of spending her new free time traveling, she spent the next two years tending to her ailing father, his lungs deteriorating because of mold inhalation — an aftereffect of Hurricane Matthew.

On the Saturday after Hurricane Florence dumped feet of rain on Lumberton, Powell’s father, Pernell, died.

Pernell Powell was 88 years old, two weeks shy of his next birthday. Dianne slept beside him as he slipped away. Doctors said he suffered from an enlarged heart, pneumonia and cirrhosis of the liver.

“He was a good man and father, and always visited the sick,” Powell said. “People would ask him when he was in the hospital, ‘What you doing in that bed, you’re supposed to be out visiting!’ He said, ‘Oh, it’s my turn now.’”

Powell sighed as she started packing items from her damaged house to take to her second storage unit — “One for Matthew, one for Florence.” She’s currently staying with friends across town.

The same Baptist organization that helped Powell rebuild her first house has already started helping her prepare her new — and newly damaged — house for repairs.

FEMA officials last month also reached out to Powell.

“They left a message on my phone: ‘Dianne, we’re referring you to take out an SBA loan.’

“I already took one out for Matthew,” she said, shrugging her shoulders. “I can’t afford to take another one out. I’ve got to live.”