In France, #MeToo protests force a rock star who killed his girlfriend to give up tour

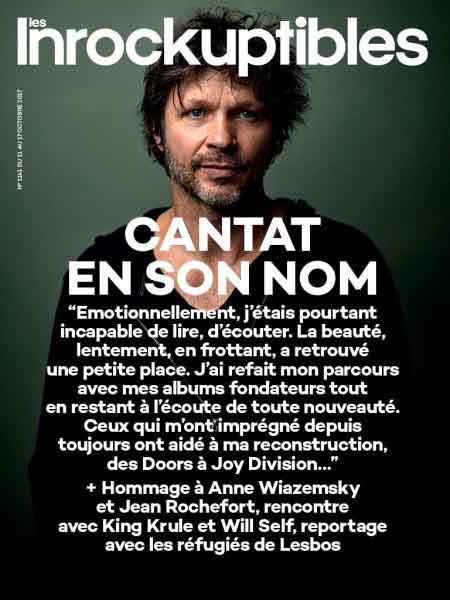

Women from feminist organizations hold photos of late French actress Marie Trintignant and placards reading “If killing is an art, award Cantat with every victory” on March 12, 2018, in Montpellier, France during a Bertand Cantat concert. Bertrand Cantat killed his actress girlfriend, Marie Trintignant, in 2004.

The #MeToo movement continues to resonate around the world, and France is no exception. There was a remarkable development there this month.

A notorious rock singer was pressured into canceling the remainder of his tour in the face of a public outcry. Bertrand Cantat, once the frontman for the popular 1990s band Noir Désir, had been attempting several career comebacks over the past decade. But faced with mounting protests, he had to give up. This is why.

In the early morning of July 27, 2003, Cantat beat his girlfriend so badly she fell into a coma. Actress Marie Trintignant was pronounced dead five days later in a Paris clinic. Her death was shocking news in France, especially because both Trintignant and Cantat were beloved celebrities at the height of their careers. At the time, many media outlets presented the killing as a crime of passion, an incandescent love that had turned deadly.

Cantat was convicted of the killing. He served four years of an eight-year sentence before being released on parole. Determined to make his musical comeback, he did so, gradually. But in 2010, there was more trouble: his wife, Krisztina Rady, killed herself. She, too, had alleged abuse at his hand. No charges were brought against Cantat who, in spite of protests along the way, continued to perform.

Related: Millions say #MeToo. But not everyone is heard equally.

Former Minister of Women’s Rights and Member of Parliament Laurence Rossignol says the magazine cover seemed like a provocation.

“I’ve often wondered whether in the case of an artist who’d have committed a racist crime instead of a femicide,” she says, “[if] there would be as many people to quickly plead the cause of his or her right to forgiveness. In the indulgence this cover shows towards Bertrand Cantat, there is something specific to cases of violence against women.”

Many fans were willing to forgive, but crowds heckled Cantat outside many of his concert venues and called him an “assassin.” Prominent concert halls canceled his performances, and Cantat himself withdrew from summer festivals. But he posted an open letter on his Facebook page apologizing for the magazine cover and pleading for the right to do his job. Even so, French radio journalist Yann Bertrand, who attended Cantat’s last concert in Paris this month, says the singer has not exactly been contrite.

Related: Has the #MeToo movement gone too far or not enough?

“On stage, Bertrand Cantat was arrogant, he criticized the media, he said basically, ‘fuck you,’ that’s what he said, so his fans were really irritated by this attitude.“

Raphaëlle Rémy-Leleu says Cantat, like many abusers, is trying to paint himself as the victim. She’s the spokesperson for the advocacy group Osez Le Féminisme, or ”Dare Feminism.”

“The strategy is to create the image of someone who is repentant and persecuted,” she says. “It started with the magazine cover a few months ago, it’s toxic and clearly indecent.”

In 2016, according to the ministry of the interior, one woman died every three days in France at the hand of a husband or companion. Rémy-Leleu says it’s important to continue to raise awareness about this issue. But some view her group’s actions as a kind of censorship. In a recent op-ed this month, prominent criminal attorney Marie Dosé called feminist demonstrators “puritanical” and compared them to anti-abortion groups who picket outside clinics in the US. Dosé says the singer has paid his dues to society and should be allowed to do his job. Raphaëlle Rémy-Leleu agrees only to a point.

“Of course he has the right to reintegrate,” she says, “but society is not obligated to offer him the same position he had, especially when this is a position of power and of public exposure. Our society accepts the idea of applauding a man on stage who has killed a woman. There is something disturbing about that.”

Rémy-Leleu and Laurence Rossignol liken Cantat’s case to that of film director Roman Polanski. Polanski, whose career has flourished in Europe, is still wanted in the US for statutory rape, a case dating back to 1977. Last fall, the prestigious Paris Cinémathèque honored Polanski with a film retrospective. Rossignol says this kind of reward sends a confusing message.

“You can go on watching Polanski’s movies and listening to Cantat’s songs,” she says, “but we need to stop revering the men. We need to stop separating the violent man from the great artist, they’re the same person. When Polanski is asked to preside over a movie industry event and when Bertrand Cantat is going on tour, these men are being sent messages of support and absolution.”

Rossignol says as much as she used to love Cantat’s songs, she feels queasy listening to them now. A sentiment now shared by music reporter Yann Bertrand who reviewed Cantat’s last album.

“When I listened to the album, I listened to the songs, and you cannot help but think about what he did. That’s my opinion,” he says. “You can respect the man, the artist, but when I listen to Bertrand Cantat now and when I see him on stage, it’s impossible to separate him from what he did.”

Laurence Rossignol says canceling the rest of his tour was the right thing to do for Cantat, given the growing controversy and opposition he was facing. She notes that the relatively new women’s protest movement in France was really encouraged by #MeToo.

“It’s clear that #MeToo has given a formidable boost to what was building here over time, and it allowed women’s complaints to be heard,” she says.

Cantat hasn’t announced yet whether he intends to perform ever again, and his lawyer didn’t respond to an interview request. But his legal troubles may not be over. A new investigation was reopened earlier this month about the circumstances of his wife’s suicide.