Britain built an empire out of coal. Now it’s giving it up. Why can’t the US?

Miners leave after working the final shift at Kellingley Colliery on its last day of operation in north Yorkshire, England, December 18, 2015. Kellingley was the last deep coal mine to close in England, bringing to an end centuries of coal mining in Britain.

Editor’s Note: This story was broadcast as a 2-part series. Audio for each part is below.

Part One: A divisive national strike in the 1980s stripped the once-dominant UK coal industry of its economic and political influence.

Part Two: 30 years after the strike, a ground-breaking climate law meets almost no opposition and leads to an almost total phase-out of coal.

The UK, perhaps more than any other country in the world, was built on coal.

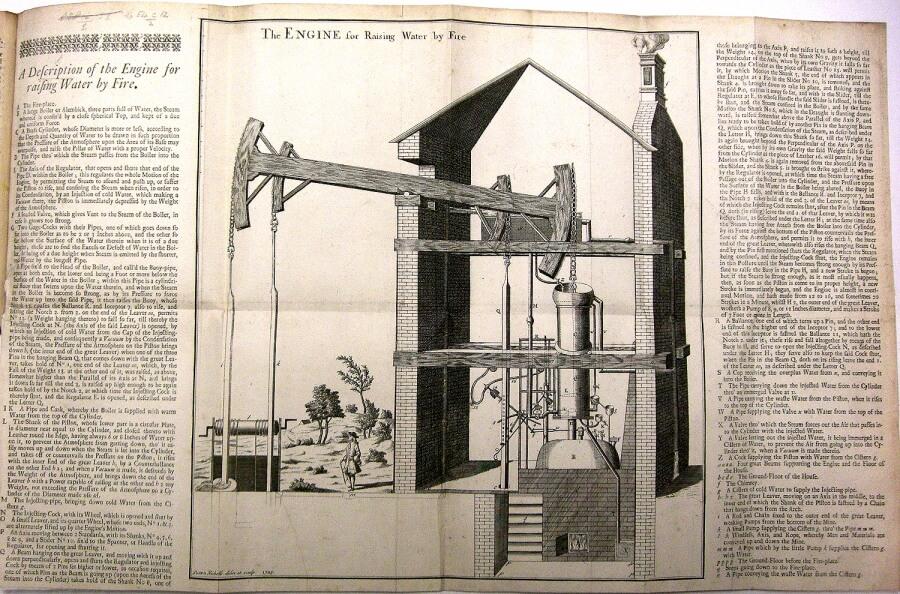

The first successful steam engine was invented to pump water out of British coal mines. Coal powered the railroads and ships that built the British empire. It helped the country survive two world wars, and at its height between those wars, coal mines employed 1.2 million people.

So this winter, when the United Kingdom announced its plan to stop burning coal for electricity by 2025, the shift was seismic.

The announcement signaled the dethroning of King Coal in a country where it had reigned for more than a century, and where just six years prior it provided more than 40 percent of the nation’s energy.

How did this happen in the UK at a time when leaders in the US were moving in the opposite direction by promising to end the “war on coal”?

The answer lies not in technological innovation, but in a profound cultural shift that began decades ago in coal field communities across the UK.

A country built on coal

The historic shifts were felt nowhere more acutely than in Yorkshire, the country’s largest coal region and a part of northern England where farms and villages sit on top of vast coal reserves.

It’s been called England’s Texas, but without the sun and guns.

For generations, entire communities there were built around the coal pits. Mines had their own social clubs and brass bands. Coal companies sponsored bus trips to the seaside and swimming nights at local pools for mining families.

As a third-generation miner, it was a way of life Shaun McLoughlin knew well.

“Where I lived in particular, when people went to the local schools, it was sort of taken that unless they went on to university, they would just move into coal mining,” says McLoughlin, 57, who grew up in public housing in Castleford, a small West Yorkshire village that was surrounded by mines. The son and grandson of miners, he followed in their footsteps at age 16.

McLoughlin, who today has neatly trimmed gray hair and an efficient, matter-of-fact way with words, enrolled in an apprenticeship program that paid for college and put him on a track toward management.

He started in the industry in the 1970s, at a time when its future looked brighter than it had in years.

The UK had hit peak coal production back in 1913. By the 1920s, jobs started declining as mechanization, decreasing demand and competition from other fuel sources started to impact the industry. The decline in mining jobs continued for decades.

But in the 1970s, when McLoughlin was graduating high school, an oil crisis sparked by embargoes gave the coal industry a temporary reprieve. The mines stopped hemmoraging workers, new investments in the industry were promised, and for a few years, at least, things started to look up again for King Coal.

“When I started in the industry, I was told you’ve got a job for life. You’ve got a job for life, lad, as they say ‘round these parts,” says David Murray, who grew up near Manchester and also started in the industry in the 1970s.

“Things started changing in the early 80s,” Murray says.

A coal strike in 1984 and 1985 divides a nation

In 1984 the government-backed National Coal Board announced plans to close 20 inefficient coal pits, and most of the country’s miners went on strike to protest. The yearlong strike that resulted divided the country and would change both organized labor and the energy industry in the UK.

At the time, Yorkshire miner Shaun McLoughlin was recently married and had a mortgage. Making ends meet was tough, but he dared not cross a picket line.

“Being a third-generation miner, you knew that it was a sin to break the strike,” McLoughlin says.

But the strike lacked nationwide consensus, and some miners kept working. Police trying to help them get to work clashed violently with picketers on the streets. News coverage showed lines of picketing miners facing off with police in riot gear. Miners threw bricks and marbles. Cops put picketers in headlocks and dragged them from the front lines.

The country, watching all this on TV, was bitterly divided. Some supported the police, while others backed the miners.

“It split families, it split brothers,” McLoughlin says.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who had run on a platform of busting union power, waged a public relations battle against the picketers.

She called them “the enemy” and their tactics “intimidation” and “unlawful assembly.”

“All the publicity on TV was showing the miners as being basically thugs,” McLoughlin remembers. “There was a lot of bad feeling toward the miners.”

Despite the mining union’s hopes that a strike would bring the country to its knees, the lights stayed on in the UK. And the violent clashes with police turned public opinion against their cause.

After a year, the striking miners admitted defeat and went back to work.

“There was a sense before the strike of the industry being so important, and I just think the industry lost that importance politically, economically, and everything,” Murray says.

“And the government was free then to carry out the pit closure program at an accelerated rate,” McLoughlin says.

Declining domestic mining industry leaves coal powerless

In the decade that followed the strike, most of the country’s deep mines closed and the number of people employed in the industry plummeted from 139,000 to about 7,000.

At the time, however, the motivation was economic, not environmental. The UK was still burning coal in power plants, it just increasingly relied on cheaper, imported coal.

But the shift to foreign coal had a major political impact. As local miners were laid off, the domestic coal industry lost its power.

“Their ability effectively to lobby was reduced over time,” says Grant Wilson, an expert on energy systems at the University of Sheffield. “One can see the miners’ strikes as being really quite a momentous change for the United Kingdom.”

This momentous change would later help make it possible for the UK to establish a national policy of decarbonization, but it would take more than two decades for that policy to emerge.

Related: Germany talks a good game on climate, but it’s still stuck on coal

Climate change lands on political radar in the UK

By the turn of the millennium, environmentalist and lawmaker Baroness Bryony Worthington says, the issue of climate change was starting to work its way into the UK’s politics.

“There was a real sea-change in attitude toward climate change,” says Worthington, who today is a member of the House of Lords and heads the Environmental Defense Fund’s European branch.

“You definitely saw more discussion, papers being published, and it started to get political attention in a way that it hadn’t,” Worthington says.

To try to bridge the gap between the country’s green ambitions and its coal-reliant reality, Worthington helped write what would become the UK’s Climate Change Act, the most sweeping law of its kind in the world.

The legislation set a legally binding target of cutting carbon emissions 80 percent by 2050, and required five-year plans to help keep the government on track.

With little industry pushback, the UK passes landmark climate legislation

Around the same time that public consensus for climate legislation was forming in the UK, things were moving in the opposite direction in the US.

Climate change was becoming a politically polarizing issue.

In 2009, fossil fuel companies were spending record amounts lobbying Congress as it considered climate change legislation. Years later, US coal companies fought fiercely against the Clean Power Plan, which, had it gone into effect, would have closed coal-fired power plants to reduce carbon emissions.

Viewed through the lens of American experience, passing climate legislation in the UK was an astonishingly frictionless experience.

Worthington says while lawmakers were working to get the Act passed, there was no real opposition from fossil fuel companies or workers.

“That was not the main problem,” she says.

Some government officials worried about the economic impact of the law. But Worthington can’t remember any pushback from coal interests. And oil companies Shell and BP had actually been lobbying for similar legislation for years.

“There were not the same level of climate skeptics that we see today, we didn’t have that very well-resourced, very highly organized opposition,” Worthington says. “That was not a feature.”

Across the pond in the US, a few big coal companies still had outsized political influence in key states, and employed more than 130,000 people. But the coal industry in the UK was a shadow of its former self, and employed only about 6,000 workers.

So the UK Climate Change Act passed into law in 2008.

Carbon tax “flips a switch” in UK energy sector

To meet the requirements of the act, the UK established a carbon tax in 2013. That tax eventually made coal more expensive than natural gas, and when that happened, Wilson says, it’s like someone flipped a giant switch.

“I think one of the things that really has taken many people by surprise, myself included, was just simply the rate of that change, the tipping point,” Wilson says.

Under-used natural gas capacity that had been built up during a “dash for gas” in the 1990s was turned on, and coal-fired power plants were turned off. From 2012 to 2017, coal dropped from supplying more than 40 percent of the UK’s electricity to just 7 percent.

“For any modern industrial economy to change a third of its electricity supply in a six-year period, it is really astonishing,” Wilson says.

Renewable energy also picked up some of the slack: It soared from producing about four percent of the country’s electricity to almost a third.

Last deep mine in the UK closes, ending a way of life

The writing was on the wall for the end of coal in the UK, and in November of 2015, it got a date on the calendar.

Just ahead of the UN climate change summit in Paris, the UK’s Energy Secretary Amber Rudd announced the country would stop burning coal for electricity in a decade.

“It cannot be satisfactory for an advanced economy like the UK to be relying on polluting, carbon intensive 50-year-old coal-fired power stations,” Rudd said. “Let me be clear: this is not the future.”

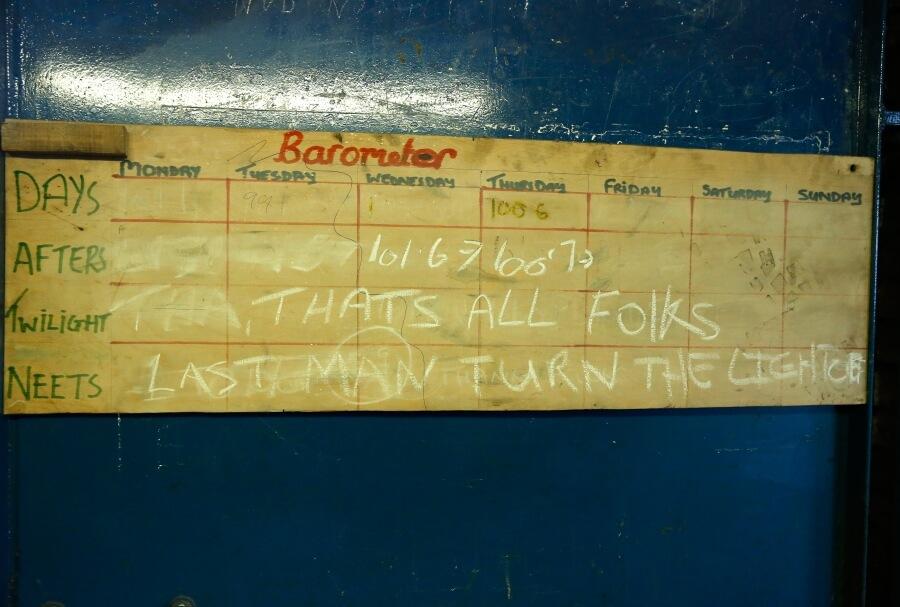

A month later, the very last deep mine in the UK closed.

The mine was Kellingley Colliery, which at its height employed more than 2,000 people. It’s where McLoughlin, the Yorkshire miner, started his career in 1977 as an apprentice and ended it nearly 40 years later as the mine’s manager.

“We were the last miners,” says McLoughlin, who remembers fielding media interviews all day after the mine sent the last shift of workers underground at 6 a.m. that December day.

“It was very emotional, there were lots of tears on site,” McLoughlin says. “Saying goodbye to a lot of colleagues that I’d worked a long time with, (it was) a very sad day, really.”

McLoughlin visited the site of the mine one morning early this spring, when it was quiet enough to hear birds chirping in the parking lot.

Related: In Germany, miners and others prepare for a soft exit from hard coal

He remembered what it was like during the boom years, when he would have to jockey for a parking spot during shift changes and cars would be backed up down the road.

The morning he visited, the parking lot was nearly empty. The few cars there belonged to demolition workers.

“(It’s) really sad to look at this great industrial site as a state of demolition,” McLoughlin says.

The mine shaft has been plugged with concrete.

Most of the buildings have been razed, including McLoughlin’s former office building, which is now just a pile of rubble.

Coal-fired power plants closing as well

This year, the UK government finalized its plan to phase coal out of the UK’s power mix by 2025.

This is good news for the environment. But the turn away from coal has been rough for those living in the coal fields, who are still more likely to be unemployed and have lower wages than the national average.

McLoughlin for one doesn’t think the pain inflicted on coal country is for a good cause.

“I’m a bit of a skeptic on this one,” he says. “I think the small amount of coal that the UK burns isn’t going to make much difference to the climate change.”

The good wages, overtime and bonuses McLoughlin earned in the mines launched him out of public housing and provided a good life for his family, including his two adult sons. Today, he thinks the government is turning its back on people like him.

“I look at the wages the mining industry paid, and I looked at what a really good living it’s provided me with. And I see my youngest son now is a schoolteacher, and he just works five days a week and has no means of boosting his income, so they do struggle,” McLoughlin says. “I really feel sorry for young families of today wanting to bring a family into the world.”

But McLoughlin seems to be in the minority, even in Yorkshire.

Even as the coal-fired power plants that were built near the UK’s mines start closing, bringing more layoffs to coal country, local communities don’t seem too worried.

Walking down the main street in Eggborough, which sits in the shadow of a Yorkshire power plant set to close this fall, coal doesn’t seem like a vibrant industry or a major employer.

It seems like history.

“It’s inevitable isn’t it?” says Robin Heath, who retired not long ago from a job working at another coal-fired power plant nearby. “(Coal) has been on its way out for years. It’s a shame, but time moves on, doesn’t it?”

Three friends drinking coffee with Heath at a café in the village of Eggborough, friends who also spent their careers working at coal-fired power plants, say they feel the same.

“I think it’s inevitable,” says Dave Wiles. “Coal has had its day. If you believe all the scientists and experts on the damage its doing, which I think there’s enough evidence there now to support it, I think we are going the right way.”

Coal remains part of the UK’s heritage

Shaun McLoughlin and his colleagues at Kellingley have moved on since the last deep mine in the UK closed with much fanfare in 2015.

After nearly four decades working in mines, McLoughlin started working at a museum dedicated to the industry, the National Coal Mining Museum, which operates on the site of a mine that closed in the 1980s.

The symbolism is not lost on McLoughlin.

“It is ironic, yes,” he says, after showing me an old-fashioned cage elevator that still drops down a shaft opened up for mining in the late 1700s.

The elevator no longer transports miners going to work underground, of course. It carries kids on school trips — kids whose grandfathers might have worked in the mines but who often have never seen coal before.

“There’s children now growing up that don’t know what coal is,” McLoughlin says. “Once (the country) stops burning coal, they’ll not realize that coal fueled the industrial revolution of Great Britain and put us where we are on the map.”

McLoughlin hopes that won’t be true for the kids he meets at the museum. Coal may have quickly fallen from favor as a fuel source in the UK, but he wants them to know it was an important part of the country’s history.

This story was updated to change references to Britain and the United Kingdom.