Germany talks a good game on climate, but it’s still stuck on coal

A section of the 33-square-mile Hambach lignite mine in Germany's Rhineland coal fields, whose coal-fired power plants, run by power giant RWE, are one of Europe's largest sources of CO2 emissions.

Just outside of Cologne in western Germany, about 40 miles from where UN climate delegates are meeting this week, the 12,000-year-old Hambach Forest is a vast, leafy cathedral of beech and oak. Except for the rustle of dead leaves underfoot and the occasional burst of birdsong, it’s pretty quiet. But it turns out it’s a great place to get an earful about Germany’s vaunted climate leadership.

“Germany is not the greenest country in the world,” says a climate activist who refers to himself as Tom.

Germany has long pushed stronger global action to fight climate change. But Tom — who uses a pseudonym over fears of being targeted by police — says the reality is quite different. “It’s one of the biggest CO2 producers in the world,” he says. “What we have here basically is the best country in greenwashing.”

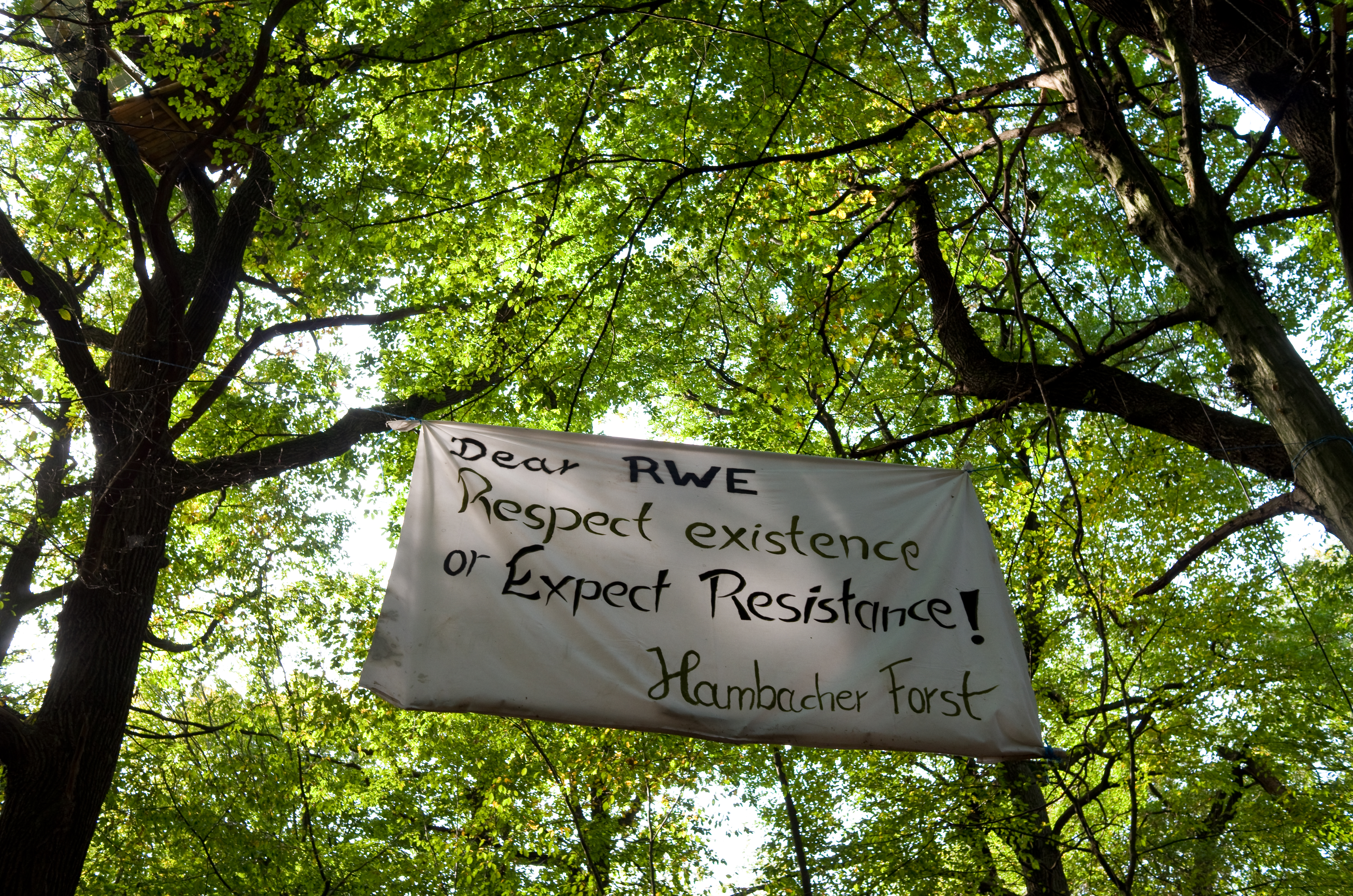

Tom is one of dozens of climate activists who’ve been camping year-round in ramshackle treehouses here for five years, “occupying” the Hambach Forest, blocking roads and clashing with loggers and police in an effort to protect the forest from being cleared.

The threat comes from an ever-expanding coal mine just next door, owned by the energy company RWE. It’s already one of the largest of its kind, and there are plans for it to get even bigger. The impending expansion would swallow the forest and a nearby town to get at a seam of lignite, or brown coal, underneath.

Tom says it’s not just about saving the trees. It’s about saving the planet.

Related: At this year’s climate summit, some Americans declare, ‘We’re still in’ the Paris Agreement

“I am not demanding this, the f***ing planet is demanding this,” he says. “It is necessary. If we if we want to stop or reverse climate change, we have to stop the brown coal as soon as possible.”

It may come as a surprise to people outside of the country that Germany still burns a lot of coal — more than anyone else in Europe. Forty percent of its electricity still comes from coal-fired power plants, a bigger share than in the United States, and most of that is brown coal — one of the dirtiest fossil fuels. Germany mines more brown coal than any country on Earth, and its coal-fired power plants are one of Europe’s biggest sources of CO2 emissions.

Related: Britain built an empire out of coal. Now it’s giving it up. Why can’t the US?

It’s a somewhat awkward reality for a country that’s widely seen elsewhere as a leader on climate policy, says researcher Timon Wehnert of the state-funded climate think tank Wuppertal Institute.

“We Germans claim we are going to be the climate champions,” Wehnert says, “and on the other hand we have the largest share of brown coal in our electricity mix,” he says.

To be fair, Wehnert says, Germany is transforming its energy sector. It already gets a third of its electricity from renewables, and it’s shooting for 80 percent by 2050. But for now, the country is way behind on its goal of cutting carbon pollution 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2020. If Germany is serious about achieving its climate targets, Wehnert says, “we need to phase out coal.”

But even in climate-conscious Germany, that’s been a tall order. Coal has been a source of domestic fuel, jobs and pride for decades. Although the country has nearly completed a market-driven phaseout of mining for hard coal, or anthracite, thousands of people still work digging up soft, brown coal in places like the Hambach mine.

See also: In Germany, miners and others prepare for a soft exit from hard coal

Germany’s continuing dependence on brown coal is also an unexpected consequence of the country’s surge in renewables. All that new wind and solar power has pushed prices on Germany’s wholesale electricity market down and made power from imported natural gas — a cleaner-burning fossil fuel — relatively more expensive than domestic coal.

“The market is not driving out coal, but the risk is [that] the market is driving out gas,” Wehnert says.

The pit at the Hambach mine is so big — 33 square miles — that standing at one end, the huge machines digging in the middle look like insects buzzing in the middle of a giant, dirty sandbox. On the horizon, smoke pours from coal-fired power plants.

“I am not demanding this, the f***ing planet is demanding this,” Tom says. “It is necessary. If we if we want to stop or reverse climate change, we have to stop the brown coal, as soon as possible.”

It’s quite a sight, and there’s an overlook for people who come to see it, with a playground and a cafe. Several older women drinking coffee there one day recently didn’t want to give their names but had plenty to say.

“We need to use less of it,” says one. “It’s dirty.”

The others immediately disagree.

“We still need it!” say two.

“What’s the alternative?” asks another.

It’s a debate that’s happening all over Germany, says Bill Hare, founder of the Berlin-based research group Climate Analytics.

“Public opinion has pretty much changed,” Hare says. “If you think about discussing a coal phaseout around the year 2000 in Germany, it was almost a taboo subject,” he says.

No longer. Coal still has its partisans, but a majority of Germans say it’s got to go. And now Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government says it agrees, sort of.

Ahead of September’s elections, Merkel’s governing CDU/CSU coalition for the first time promised a coal phaseout — but without setting a date. Now, they’re trying to form a new government with environmentalist Greens and the pro-business FDP, and coal policy is a big sticking point in the talks. The Greens want to start closing coal-fired power plants now, and finish by 2030, but the other parties are shying away from deadlines.

Hare says it’s a delicate moment to be hosting the COP 23 climate conference, but that the global spotlight could be a good thing.

“We Germans claim we are going to be the climate champions,” Wehnert says, “and on the other hand we have the largest share of brown coal in our electricity mix,” he says.

“The international community is creating pressure on the negotiations,” he says. “I’m hoping that the COP does actually move this forward.”

All of which provides just the tiniest bit of encouragement to Tom, the Hambach forest tree-sitter.

“In this system, for sure … you could call it progress,” he says.

“We know that technically there’s not a big switch that you turn off and then everything is gone. We know that everything is a process,” Tom says. “But we see that … we are running out of time.”

The climate may be running out of time, but the Hambach forest definitely is. Later this month, the mining company will come for the next round of clear-cutting, and the tree-sitters will have to decide whether to stay and fight, or find a new platform for their protest against Germany’s appetite for coal.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?