Awa Timera works in corporate recruiting in France. She says it can hard to put your finger on discrimination in France because it's often subtle.

Last fall, French President Emmanuel Macron announced a program to target disproportionately high unemployment among young people in France’s heavily immigrant neighborhoods. Macron said the government will pay bonuses of up to $20,500 to companies that hire people from designated priority areas.

“We are helping people,” Macron said. “We’re helping them to be mobile, to succeed in their neighborhoods or elsewhere, but to access a stable job.”

Related: How do you talk about gender when the words ‘simply don’t exist’ in your language?

During his campaign for the presidency, Macron floated the idea of a targeted affirmative action-style program to aid young people from immigrant backgrounds. But this program would be structured along more traditional lines for France, which has preferred a geographical to a race-based approach for government programs.

Still, the existence of hiring discrimination is a well-known obstacle for immigrants in France and their descendants, though it’s rarely stated explicitly.

Related: Unaccompanied minors in Paris face X-ray tests and other Kafkaesque hurdles to proving their age

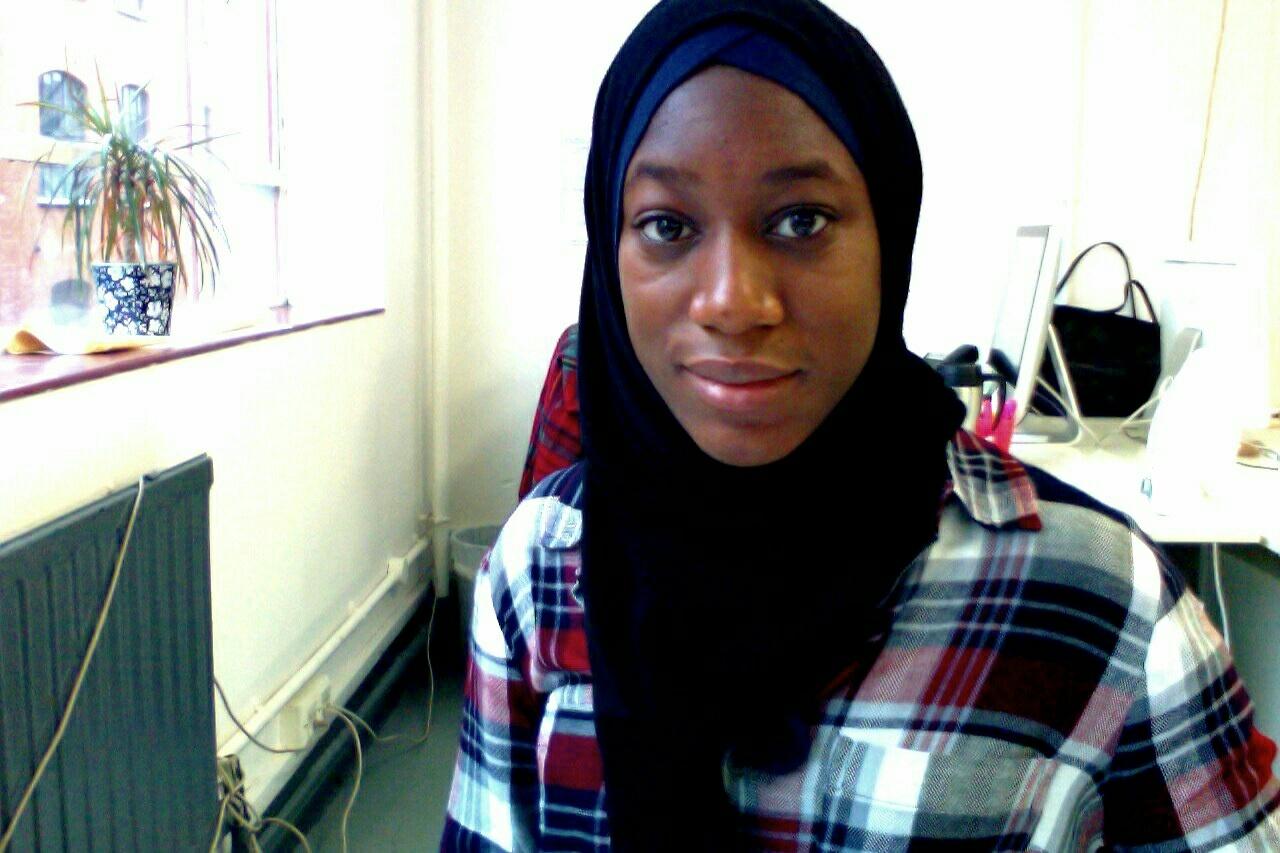

Awa Timera, 26, works in corporate recruiting. Her last job involved narrowing down lists of candidates for clients. She says on one occasion, a client who was hiring for a management position rejected all of her proposed candidates because of their ethnic backgrounds.

“The client said, ‘I don't want black or Arabic people,’” Timera recalls.

Timera was born and raised in France. Her parents are from Senegal.

Related: Activist ousted from French advisory council says race talk is still taboo

Typically, she says, “It's really hard to put your finger on racism because it's really subtle.” But this comment stuck with her because it was so blatant.

“I really had tears … because when it's done to people of color, it's like it's done to you," she says. "You think that people don't like you … they don't want you to have a job that you deserve.”

Nicolas Abdelaziz has the job of making discrimination more visible — as a way to advocate for changes to practices and policies. Abdelaziz works for one of France’s most well-known anti-racism organizations, SOS Racisme. As part of his job, he has an app on his phone that allows him to receive calls for about a dozen different numbers. They're for fictitious candidates that he creates to apply for jobs, apartments or whatever subject he is currently investigating.

Related: Deneuve sends a dated message of empowerment

Abdelaziz records the number of call-backs for each fictitious candidate. For each one, he submits CVs — identical except for different last names. Those names are designed to hint at whether a candidate is black, North African or white.

"Because [the candidates] have equal strength and competencies,” Abdelaziz explains, it allows him to determine that, “if there is a difference in treatment, it can only be because of their origin.”

Related: Some French men are lamenting 'the end of love as we know it'

The French call this method “le testing,” and it has been a primary strategy in France for decades to document racial disparities. SOS Racisme’s first tests in the 1990s looked at who got admitted to nightclubs.

The French government has financed large tests of major employers. On the campaign trail, Macron also pledged further efforts.

“Testing,” says Patrick Simon, a demographer, “is a very powerful tool to prove the existence of discrimination, but the problem is that it doesn't go further than that.”

In the US, these types of studies are used as a complement to larger statistics-based research; this method dominates in France because of restrictions on the collection of racial and ethnic statistics.

“The notion of ‘ethnicity,’ which I say in English, is not easy to translate in French,” Simon observes.

Since World War II and the end of the colonial period, France has largely taken the approach of de-emphasizing racial categories. Memories of the Vichy government’s deportation of French Jews in the 1940s have contributed to fears that allowing the government to collect lists of people and their ethnic or religious background could also become a tool for future discrimination.

Researchers like Simon use proxies in their research, such as parents' place of birth, but he argues that collecting comprehensive statistics would make for more efficient and compelling research and more effective anti-discrimination policies.

“Concretely, how did it happen?” he asks. “Where did it happen? How it is really reducing life chances of those who are targeted by discrimination?”

Simon has been a relatively lonely advocate on this topic for the past two decades because the taboo on collecting racial statistics has become deeply embedded in French culture.

Awa Timera, the corporate recruiter, has experience working in the United Kingdom. And she describes the first time she had to fill out a detailed form there that asked her to check a box identifying her race and background.

“It was unsettling for me because you have a box that says 'African' and I was starting to wonder,” Timera says. “My parents, they were born in Africa but I was born in France so should I say that I'm black African or I don't know. It was really weird.” She wonders, "if I tick that will I only be that?”

Timera would like to see more opportunities for people with immigrant backgrounds, but she’s not alone in her ambivalence about what steps France should take to get there. Still, Patrick Simon says her generation may propel the issue back into the spotlight.

“The young generation of blacks and Arabs [North Africans] is more and more actively denouncing racism,” he says, “and they begin to talk about ethnic statistics as well. So, it may well be that this generation, in some ways will be proactively changing the picture.”